By Alexandra Polach

A 148.5-carat Tiffany & Co. aquamarine was part of a prized collection of Tiffany gems and gemstones that was seen by millions of visitors at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

In 1894, the entire collection was purchased from Tiffany & Co. for $100,000 and donated by Harlow Niles Higinbotham, President of the World’s Fair, to start Chicago’s premier natural history museum.

In 2009, Tiffany experts set the aquamarine in a platinum and gold brooch embellished with white diamonds and named the piece the “Schlumberger Bow.” Today, the company offers jewelry under their Tiffany Schlumberger tradename to clients around the world.

Photograph taken by the author, Alexandra Polach, at The Field Museum, April 22, 2021

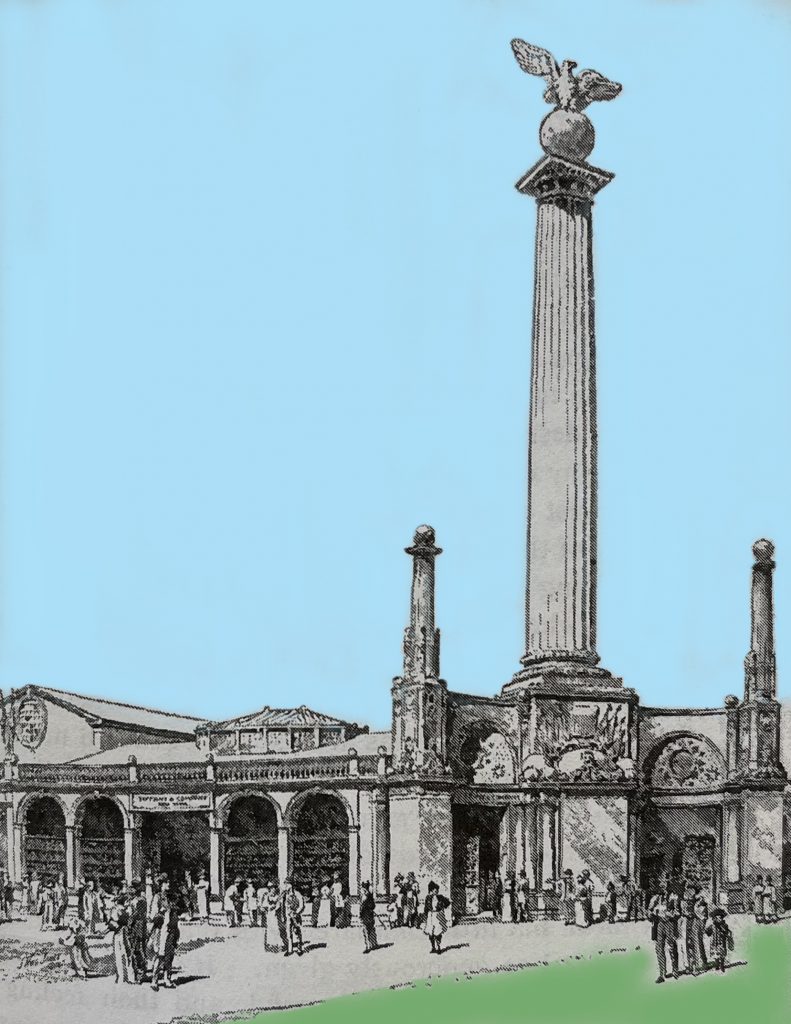

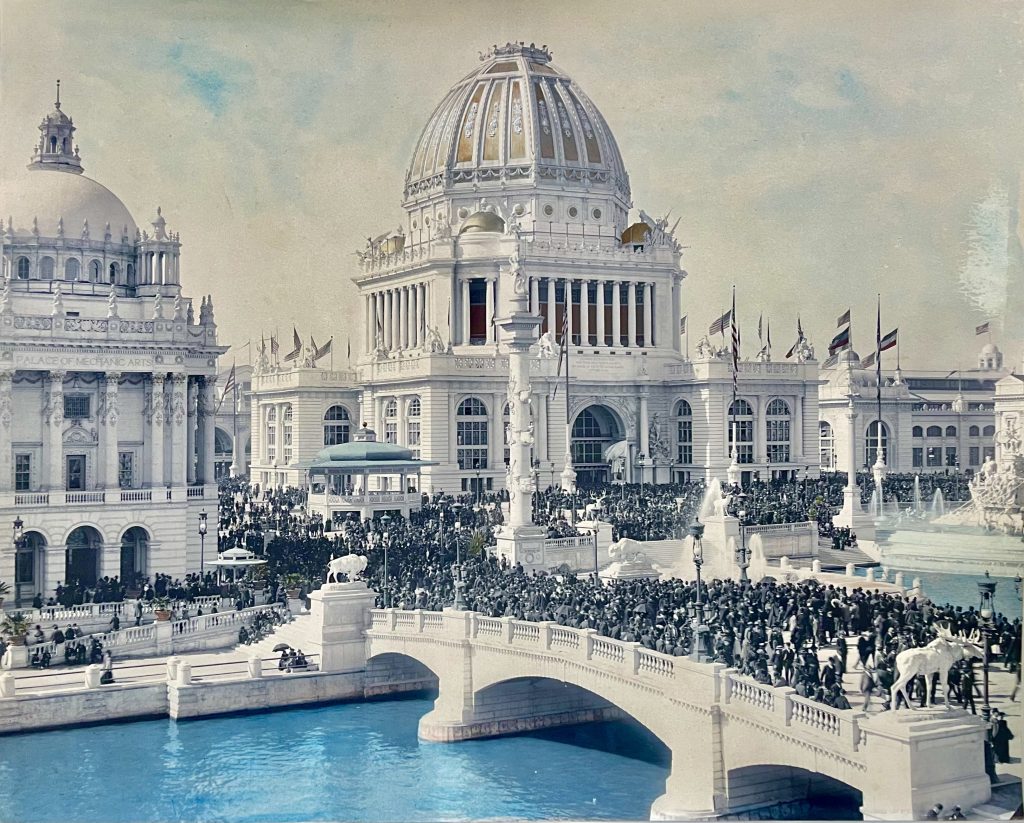

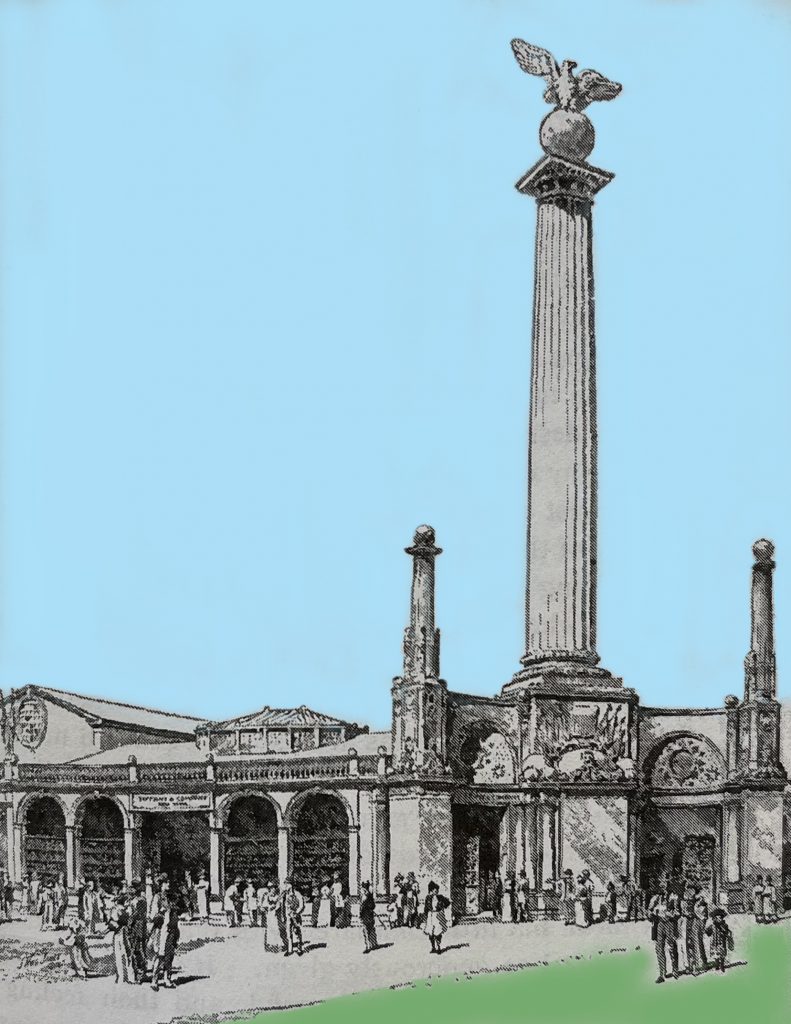

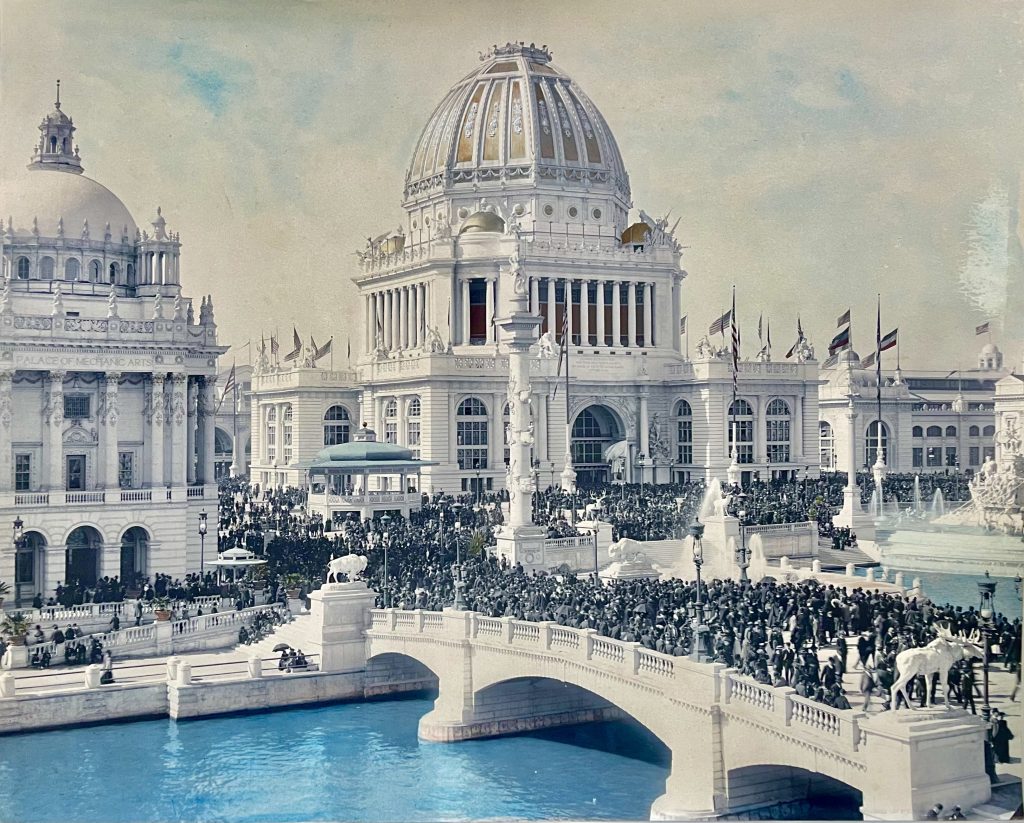

The Tiffany Pavilion in the Façade of the United States Section, Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. [1]

Photo colorized by the author

When LVMH, the world’s largest luxury group, completed its $15.6 billion acquisition of U.S. based global jewelry brand Tiffany & Company in January this year, it marked the largest purchase of a luxury company in history. The latest LVMH earnings report emphasizes the importance of this acquisition and highlights the global popularity of the 184-year-old Tiffany & Co. Brand, which was founded in 1837. This is no surprise to Chicagoans, as Tiffany is a brand that has now been celebrated and formally exhibited in Chicago to millions of viewers for more than 125 years. But we will begin this story in 1889 in Paris, France when Tiffany showed a major collection of gems at the Paris Exposition.

Photo of Founder Charles Lewis Tiffany (left) in his stunning New York store circa 1887

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tiffany & Co. Exhibits Around the World

Paris, 1889 – At the Paris Exposition of 1889, tens of thousands of visitors flocked to view a remarkable Tiffany & Co. exhibition not previously before seen. After the immense exhibiting success and after the closing of the Paris Exposition, it was the goal of Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder of the company, and his gem and jewelry team, to keep this gem collection together for the educational benefit of the greater public. Tiffany, a member of the board of the American Museum of Natural History approached a fellow Museum trustee, mogul, and avid collector James Pierpont Morgan, who agreed to buy the collection for $15,000 [2] and maintain it. Morgan would eventually donate this group of gems to the American Museum of Natural History as the Tiffany-Morgan Collection where it remains an important component of the collection today.

Chicago, 1893 – At the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, a second and equally acclaimed Tiffany gem and jewelry collection was formed and exhibited. The collection was prominently exhibited in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the Chicago World’s Fair, and the exhibits again drew great crowds and admiration.

Tiffany received national and international coverage for the collection’s triumphant exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair. The Jewelers Review, a publication from the time, wrote in August 1893 regarding the exhibition that, “Enthusiasts, watching the endless throngs crowding around the Tiffany diamonds at the Fair, have declared that were any single exhibit to be chosen for a special grand prize as the greatest international exposition the world has ever seen, the Tiffany diamonds would know no rival” [3].

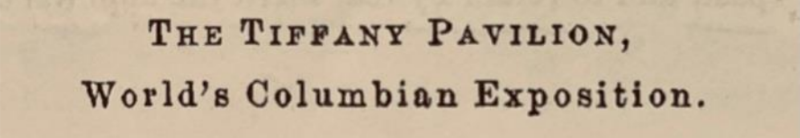

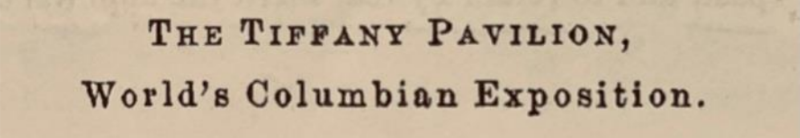

Above: Tiffany & Co. display case with diamonds at the 1893 World’s Fair. The photo was featured in the article, “The Tiffany Exhibit at the World’s Fair” in the publication The Illustrated American issue dated May 20, 1893. According to John Loring, acclaimed Tiffany & Co. historian, the set featured in the photo “contained 147 aquamarines, all cut at Tiffany’s gem cutting shop from the same crystal to assure a uniform color and the set also contained 1,848 diamonds.” [4]

Below: “The Tiffany Exhibit at the World’s Fair” article’s scrolling title. [5]

Photos from Tiffany Jewels, John Loring, Harry N. Abrams, 1999, p. 130.

Again, Charles Lewis Tiffany was proud of the tremendous crowds and positive news coverage that his firm experienced in Chicago in 1893. In a brochure published by Tiffany & Co. that year the house declared, “The testimonials…from the thousands of daily visitors, the almost unlimited generous comments of the press, and the valued technical reviews by art writers at home and abroad, have all been so overwhelming that the house accepts them not in the spirit of a personal compliment, but as a graceful tribute…” [6] The brochure goes on to state what is and was the vision that has resulted in making the Tiffany brand as popular today in the world as any jewelry brand, that Tiffany’s aim was “to excel the past, and to retain by real merit the approval of the public” [7].

Tiffany was determined to ensure that the public at large would again, as in New York, continue to have access to the remarkable jewelry and gemstones exhibited in Chicago. As the World’s Fair was ending, “prominent Chicagoans wanted to convert the fair’s collection into a permanent natural history museum” [8]. Just a short time after the close of the Fair in October 1893, Harlow Niles Higinbotham agreed to buy the entire Tiffany gem exhibit for the princely price of $100,000 [9]. This collection would continue to be permanently exhibited over the next 125 years at the Field Columbian Museum, which would later become the Field Museum of Natural History; the collection would grow to include hundreds of specimens.

The acquisition of the Tiffany gems, made possible by Higinbotham, received national coverage. The New York Times reported at the time that it “forms one of the most interesting exhibits that has been gathered abroad” [10] and that the Higinbotham donation “was one of the most important additions that has been made to the Museum” [11]. The article highlighted standout pieces that were part of the collection, including a stunning Sun-God opal which “is carved in such a delicate way to show the face of the Aztec Sun God.” Other highlights that were part of this exhibition and remain exhibited today include a 154-carat beautiful green peridot, and a collection of golden yellow sapphires, the largest weighing 102.2-carats.

Tiffany Sun God Opal

The Aztec “Sun-god Opal,” a 35-carat precious white Opal that is exquisitely carved into the shape of a human face. The opal was displayed at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and is part of the collection that Higinbotham purchased. In addition, “this Opal was mined in Mexico by the Aztecs in the sixteenth century and eventually found its way to the Field Museum in 1893, where it has remained ever since.” [12]

Photo Courtesy of Field Museum

“The Green Goddess” a 154-carat peridot gemstone. The peridot itself was displayed at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and is part of the collection that Higinbotham purchased. The peridot was set in the gold pendant with diamond embellishment, designed by Lester Lampert of Lester Lampert, Inc in 2009 for a Field Museum exhibit.

Photographs taken by the author at The Field Museum, April 22, 2021

“Sunrise”, yellow sapphires set in a gold bracelet, the largest weighing 102.2-carats. The largest sapphire was displayed at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and is part of the collection that Higinbotham purchased. The gems were set in the bracelet by designer Lester Lampert in 2009 for a Field Museum exhibit.

Photograph taken by the author at The Field Museum, April 22, 2021

With Higinbotham’s funding secured, the gems and gemstones did stay in Chicago and were moved to and installed in the new Field Columbian Museum, which was housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts Building of the Chicago World’s Fair in Jackson Park. The gems opened at the Field Columbian Museum on June 2nd, 1894, where they remained until 1921.

The Higinbotham Hall of Gems

Photo from Lance Grande and Allison Augustyn’s book, Gems, and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. The caption of the above photo as written therein reads, “The Higinbotham Hall of Gems in the Field Museum, 1893.” [13]

H.N. Higinbotham Hall of Gems and Jewels and Tiffany Window

The entire Tiffany-Higinbotham display was moved in 1921 to the new Higinbotham Hall in the current Museum building, and completely reinstalled in 1941 with “new and highly improved types of exhibition cases on bases of attractive English harewood with view-glasses supported by framework of bright polished bronze…The reconstructed hall, with its colored window of Tiffany glass opposite the entrance, provides a setting worthy of the beauty of the gems and other ornamental objects in the collection.” [14]

Photo courtesy of the Field Museum

Higinbotham’s Role and Legacy

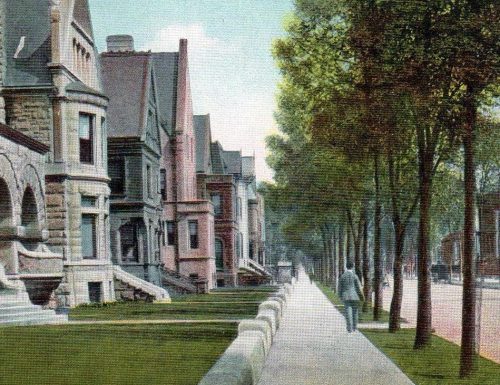

Harlow Niles Higinbotham was well-positioned to step up and fund the purchase of the entire collection and thus to make Charles Tiffany’s dream of permanent public access for his achievement a reality. His rise from farm boy to civic leader was very rapid, even by the standards of fortune building in 19th century America. His family came west to Northern Illinois from New York state in the 1830s. They bought farmland, built a mill, and settled at New Lenox, 40 miles southwest of central Chicago, where he was born in 1838. Higinbotham became one of the “merchant prince” leaders of the gilded age in Chicago and was a major philanthropist, having made his fortune as a partner in Marshall Fields’ dry goods empire. During the Chicago fire of 1871 he was credited as having used his quick wit and leadership instincts to save the firm millions by quickly moving the finest silks and other of the most valuable inventory and irreplaceable financial records from the path of the inferno to his carriage house in New Lenox. Higinbotham married Rachel Davison in 1865 when he returned from serving as an officer in The Civil War. According to scholar and literary critic Harriet Monroe’s 1920 memoir of Harlow Niles Higinbotham, an interesting fact is that Higinbotham was with Lincoln in the White House on March 8th, 1864 when the president, who Higinbotham knew well, promoted Grant to the rank of commanding general of the Union Armies.

During the planning of the Fair, Higinbotham served as a trustee, and in 1892 he was made president of the Exposition. He was president of the Field Columbian Museum from 1898 until 1908.

The Gilded Dome of the Administration Building on Chicago Day, October 9th, 1893

President Higinbotham’s Private Office looked East out over the Court of Honor and onto Lake Michigan.

C.D. Arnold, Photographer, Courtesy of a Private Collection

100 Years Ago this Month, Marshall Field’s Bequest and Higinbotham’s Plans are realized for the 1921 Building for the Field Museum of Natural History

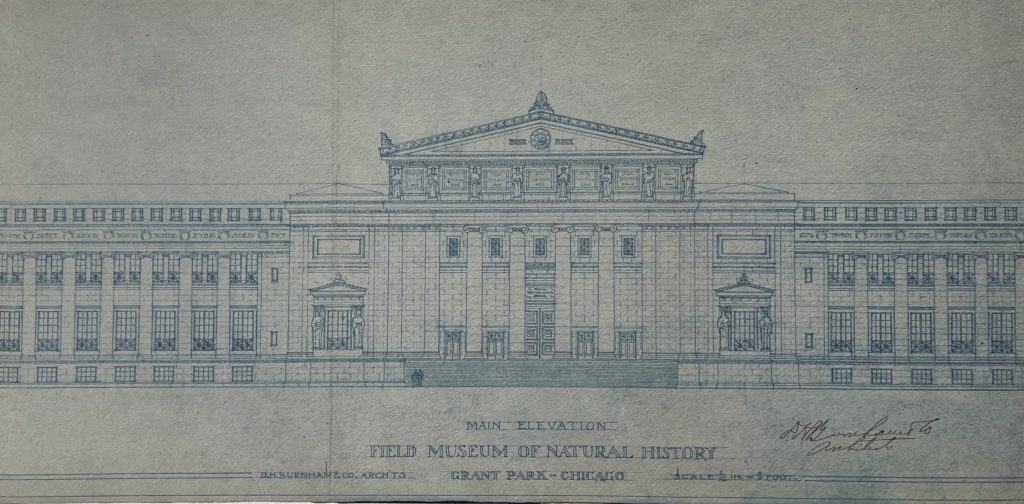

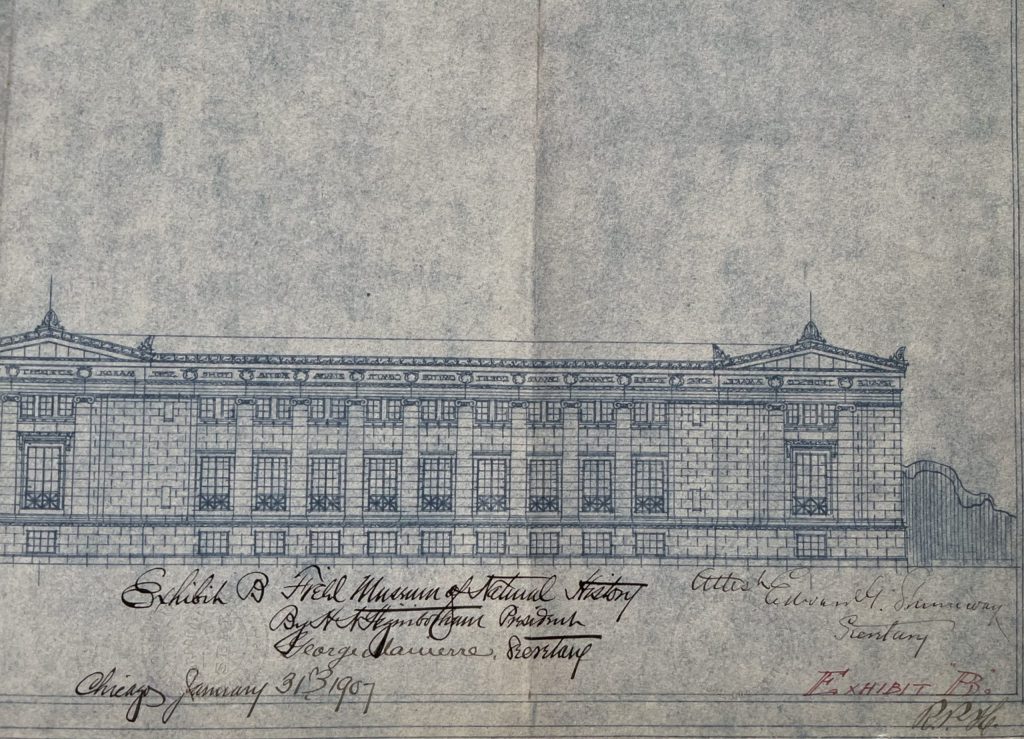

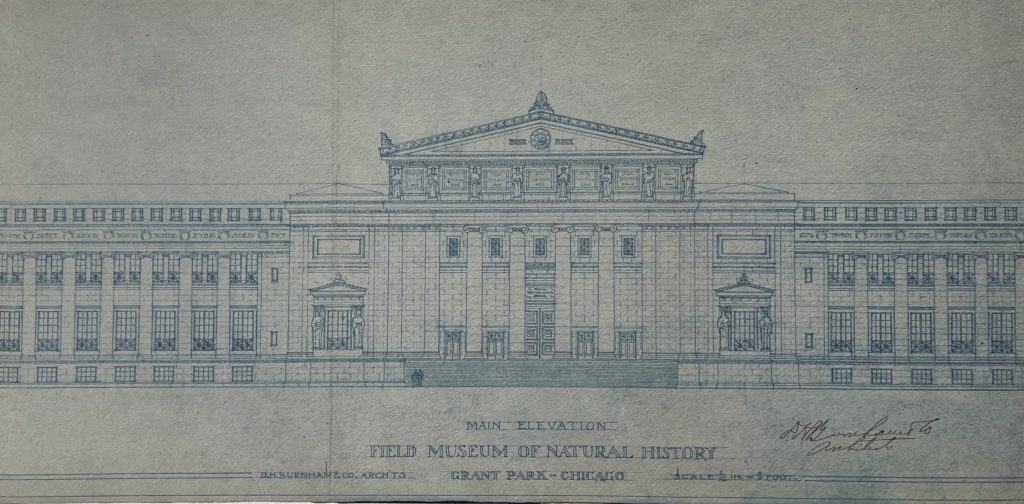

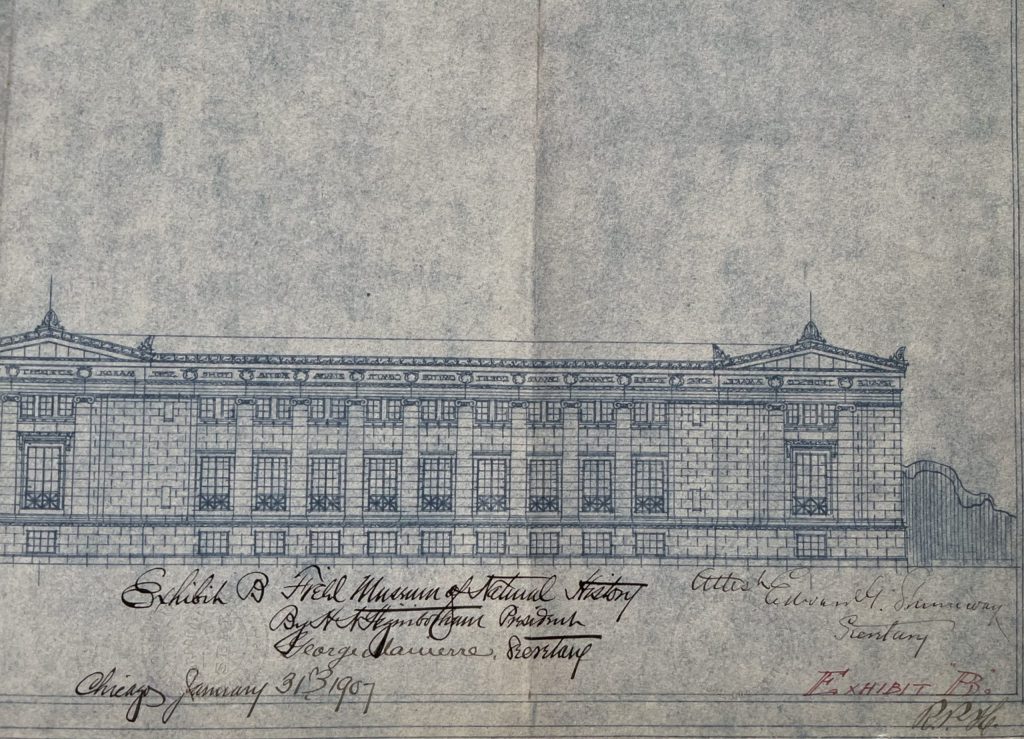

Closeups of the blueprint for the new Field Museum of Natural History building, dated January 31, 1907. Images show signatures of both Daniel Hudson Burnham, lead architect, and

Harlow Niles Higinbotham, museum president.

Courtesy of a Private Collection

When Museum benefactor Marshall Field died in 1906, it was revealed that his will included $8,000,000 in funding for a new building to replace the original (and at that point crumbling) location in Jackson Park. At the time, Harlow Niles Higinbotham was serving as president of The Field Museum; having closely worked together on the Fair, Higinbotham immediately hired Daniel Burnham to work with him to design the new structure. By January 1907, the first plans (shown above as a blueprint) were presented to the public. The Chicago Tribune wrote that the plan showed promise of “a structure which will be unlike anything ever built in Chicago, with the exception of the World’s Fair buildings” [15]. Construction of the stately, multimillion square foot marble-clad structure” which cost an exorbitant $6,750,000 [16], was completed in 1920 and opened in May 1921.

From the opening day of the new building, the Tiffany Gems in Higinbotham Hall were a top attraction. One hundred years ago this month, on May 2, 1921, hundreds of guests flocked to stand in line for their maiden visit. The Chicago Tribune, (which, at the time, was owned and published by Higinbotham’s son in law, Joseph Medill Patterson (“The Captain”) and Patterson’s cousin Robert R. McCormick (“The Colonel”)) described the new Museum’s inaugural exhibits with great praise which has continued to the current day.

Continued Higinbotham-Patterson-Crane Collecting and Support Over Three Centuries

Support for The Field Museum by members of the Higinbotham family has now continued over three centuries. Most significantly, perhaps, was the major donation of a second major collection of Tiffany & Co. gems by Higinbotham’s daughter Florence Higinbotham Crane in 1941. Mrs. Higinbotham Crane was the wife of Richard T. Crane, Jr., heir to the Chicago elevator, plumbing, industrial, and aerospace fortune and a long-serving trustee of the museum. The donation included a 97.5-carat imperial ruby topaz, which is the largest of its kind in any museum, and a stunning 341-carat faceted aquamarine, shown in photos below.

A Tiffany & Co. 97.5-carat imperial ruby topaz purchased by Florence Higinbotham Crane for the Higinbotham Gem Hall in 1941 set in a rose gold pendant designed and created by Lester Lampert of Lester Lampert, Inc. in 2009 for a Field Museum exhibit. [17]

Photographs taken by the author at The Field Museum, April 22, 2021

The “Crane Aquamarine”, a 341-carat faceted gem measuring 60 x 37 x 22 mm purchased from Tiffany & Co. and donated to the Field Museum by Florence Higinbotham Crane in 1941.

Photograph taken by the author at The Field Museum, April 22, 2021

Beyond the magnificent gemstones that Mrs. Crane donated to the Field Museum, the family’s philanthropy continued with their focus on advancing the museum’s scientific research. There is an entire hall dedicated to larger American mammals, which in 1942 was named Richard T. Crane Jr. Hall [18], after Mrs. Crane’s husband. The Cranes’ son, Cornelius Vanderbilt Crane, funded and donated the use of his yacht “The Illyria”, for the Field Museum’s “Crane Pacific Expedition” which took place in 1928-1929 throughout the Pacific Ocean [19]. The expedition prioritized marine research and enabled many Field Museum scientists and specialists to participate. In addition, donations were made by Higinbotham’s son, Harlow Davison Higinbotham, who collected art and artifacts in South America for both the World’s Fair and as donations for the Field Museum.

In the current generations, a great-grandson, Harlow Niles Higinbotham, and his wife Susan have also served on the board of trustees and as well as head of fundraising committees and events; their children are seventh-generation Chicagoans who will support the museum and its scientific mission well into the future.

Tiffany & Co, Lady’s “H” Monogrammed Diamond and Gold Lorgnette

Not all Tiffany pieces collected by the Higinbotham-Crane family have been donated to museums; pictured is a diamond-encrusted “H” monogrammed lorgnette from the early 20th century held in a private family collection.

Courtesy of a Private Collection

In writing this article, it was imperative to see these gems and gemstones in person and visit and support one of city’s most well-known institutions. A photo simply does not capture the gemstones’ magic radiance and I highly encourage you to do as I did and visit the Tiffany-Higinbotham-Crane exhibit. I personally crave authenticity and cherish craftsmanship in the brands I align with today and these gemstones show the highest level of expertise, in the way they were sourced, assembled, and faceted by Tiffany, and displayed to this day by the museum. They remain incomparable to anything you might find in the market today.

As I opened with Louis Vuitton, I will close with it. My next article will feature the stories of the Higinbotham-Patterson-Crane family’s and friends’ global travels with their hand-made, expertly crafted, and beloved Louis Vuitton trunks, purchased in Paris as early as the 1880s.

Continue reading →

Seagull photo taken from our kayak

Seagull photo taken from our kayak