Burnham without Root

By Megan McKinney

“Damn! Damn! Damn!” Daniel Burnham’s words in response to the sudden death of his brilliant partner, John Wellborn Root, were anything but extreme. The two had only begun the gargantuan two-year task of supervising America’s greatest architects in producing the spectacular 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Burnham as chief of construction, and Root, consulting architect.

The partners in their handsome Rookery office a short week earlier.

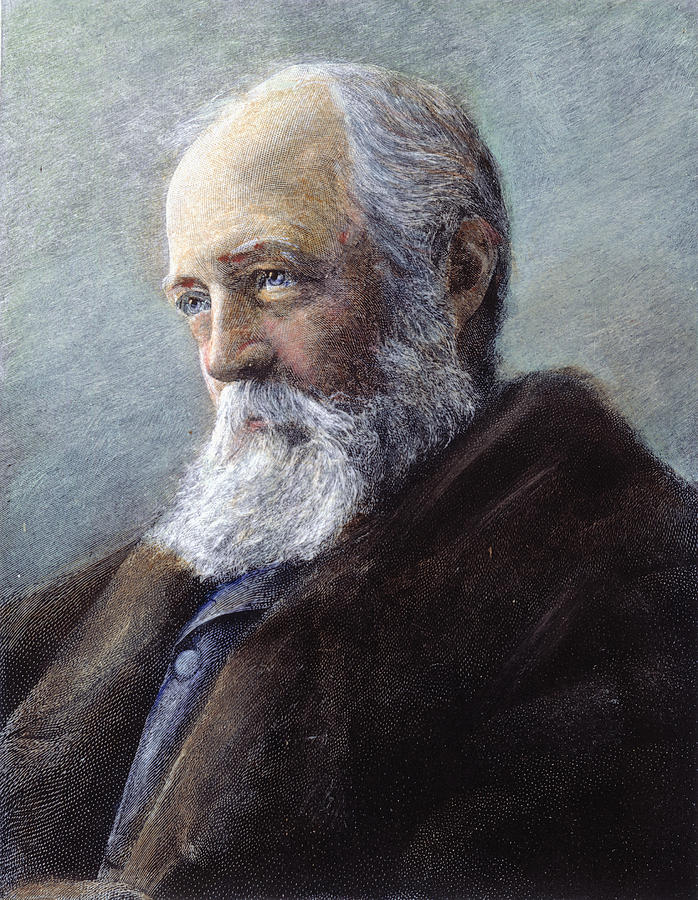

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, bent, white-bearded and old—when 68 years was old—had come out to Chicago in August 1890 with his young assistant, Henry Sargent Codman, to begin planning the lagoons, basins and canals that would be dredged to create the Fair’s basic configuration.

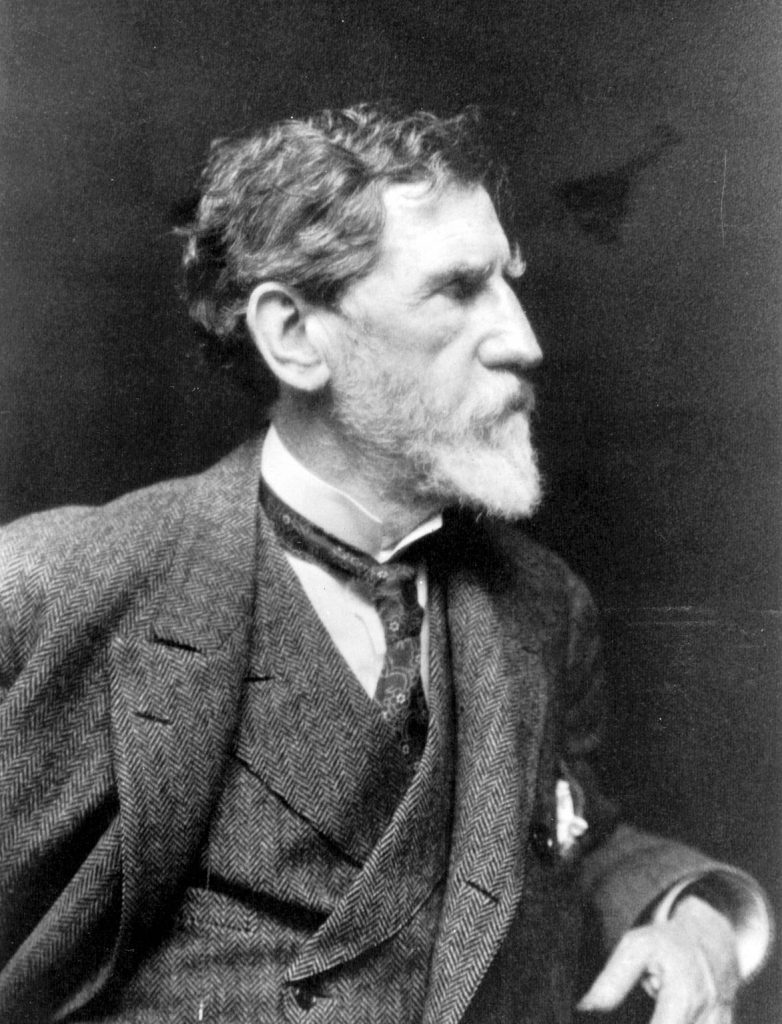

![]() Frederick Law Olmsted, creator of the art of landscape architecture.

Frederick Law Olmsted, creator of the art of landscape architecture.

The great plaster buildings would be erected in relation to the Olmsted/ Codman bodies of water, which would precede them. In the fall Root and Burnham joined the two landscape architects in sketching preliminary drawings of the temporary structures on great stretches of brown paper, for placement and proportion only. The plan was for Daniel and John to confine their work to overall planning and supervision of other architects, participating themselves in none of the design of buildings

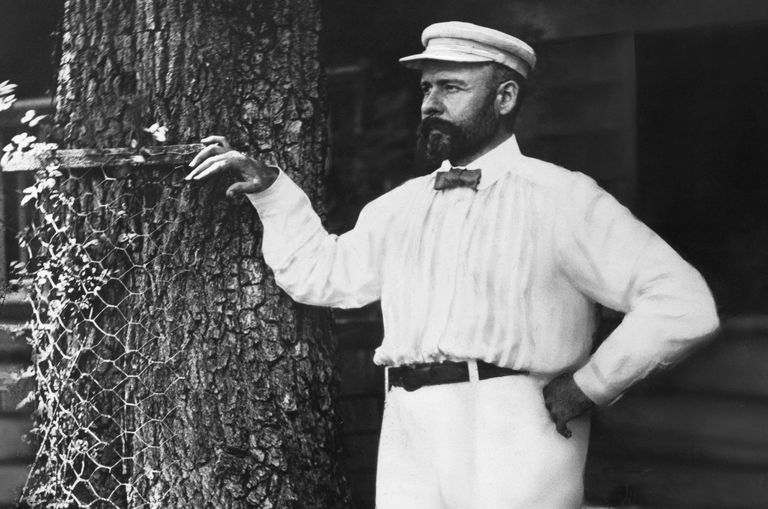

Louis Sullivan.

The Chicago architects included Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, William Le Baron Jenney and Pullman favorite Solon S. Beman.

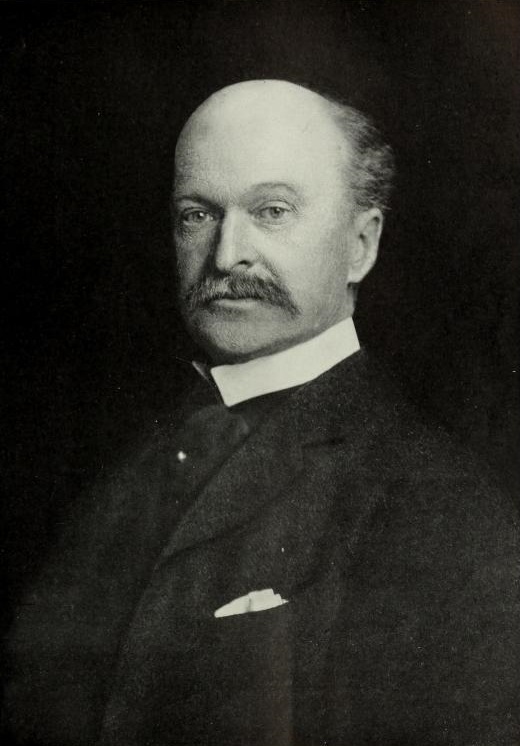

Charles Follen McKim.

Charles McKim from the towering New York firm McKim, Mead & White, was assigned a Court of Honor building, as were New York’s Richard M. Hunt and George B. Post. Boston was represented by partners Robert Swain Peabody and John Goddard Stearns. The fifth Court of Honor design would be by Bostonian Henry Van Brunt, then working in Kansas City.

They all met in Chicago in January 1891, gathering in a dismal, grey Jackson Park during the week before Root’s sudden fatal illness. The sweep of the colorless space in the deepest gloom of a Chicago winter did little to encourage the out-of-town architects who would be sacrificing valuable weeks and months of their own work to participate in the project.

Burnham’s job was to stir the men to replicate the intensity of teamwork and self-sacrifice that had won the Civil War, which he did in a speech during a Saturday night banquet. It was while they were in a meeting in Burnham and Root’s Rookery office the following Monday that a call came to Burnham from Dora Root with the news that John was ill with pneumonia. This was a chilling announcement at a time—well before the 1940’s discovery of sulfa drugs, and then Penicillin—when pneumonia was almost invariably a death sentence. Daniel left immediately for his partner’s bedside, where he remained for the next harrowing three days.

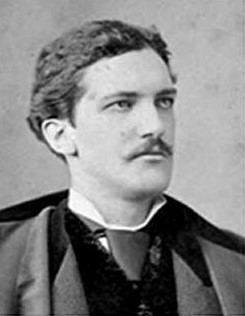

Charles Atwood.

It was a grim yet busy winter for Burnham. He engaged New York’s Charles B. Atwood in Root’s spot as consulting architect, while he alone continued the responsibility of the building of the Exposition. Atwood’s White City designs included the Fine Arts Building, which metamorphosed into today’s Museum of Science and Industry. After the Fair he remained in Burnham’s firm and would design Chicago’s stunning Reliance Building, on the southwest corner of State and Washington.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

When the architects Burnham dubbed the “Beaux-Arts boys” returned to Chicago with their sketches toward the end of February, they were joined by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the sculptor whose statue of Lincoln overlooks North Avenue at the south end of Lincoln Park. Saint-Gaudens’ White City job was “to advise on artistic matters.”

Burnham—in anticipation of the February gathering—predicted, “This will be a meeting memorable in the annals of architecture.” He was correct; the energized group—stimulated by the magnitude of the project—began the first meeting day in honing such basics as the dimensions of Olmsted’s water bodies, as well as refining detailing in and near the Court of Honor. Most memorable was Saint-Gaudens suggestion of the addition of a great statue standing in the Court of Honor basin backed by 13 columns, symbolizing the original colonies. This idea would emerge as Daniel Chester French’s mammoth Statue of the Republic, which we usually see from the rear.

Daniel Chester French’s Statue of the Republic.

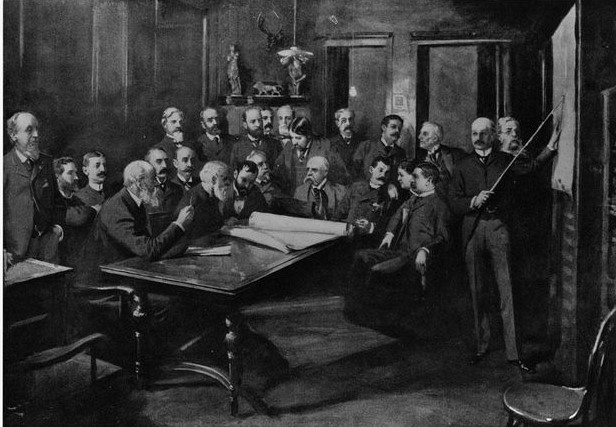

On the following day, February 24, 1891, 19th century America’s great architects, again meeting in Burnham’s Rookery office, took turns unveiling their sketches for the buildings each had been assigned. “The day went on,” remembered Burnham, “we had our luncheon on the table…it got to be quite dark and we lighted up before the meeting was through. It was still as death except for the low voice of each speaker…”

Burnham’s Rookery office on February 24, 1891.

At the end of the long day, Saint-Gaudens came over to Burnham, took both his hands, and said, “Look here, old fellow, do you realize that this is the greatest meeting of artists since the Fifteenth Century.”

Although neoclassicism would be the “frame of reference” style, it was Burnham’s insistence to his Beaux-Arts boys that “all buildings be as distinct from each other as they could possibly be.”

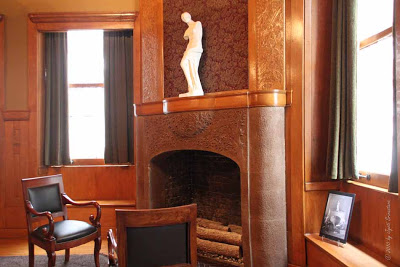

The Rookery office would soon be deserted for two years.

Within two months, Burnham moved from his now very empty office to Jackson Park and a new temporary structure that would be his around-the-clock headquarters during the construction of the fair. Coming with him was his loyal personal servant, Jackson. Staying at home in Evanston were his wife, Margaret, and their children.

Burnham’s two-year home base consisted of his own office, his personal living space, a small gymnasium and, below, a large cafeteria—although Burnham’s own meals were served to him by Jackson.

Daniel Burnham and the great architects with whom he collaborated produced a spectacular fair, which has been fully reported in many forms into a third century. It is difficult for today’s reader to appreciate the stunning impact of the World’s Columbian Exposition on those who cleaned out their bank accounts—some spending “burial money” — to travel to the fair from the small towns and farms of America. Electricity, for example. Thomas Edison had patented the light bulb only 14 years earlier; just imagine what it was for these men and women, who had traveled from their lantern, fireplace and candlelit worlds, to view the thoroughly electrified Administration Building at night during the summer of 1893.

Daniel Hudson Burnham had many years to live and several more “careers” ahead. There are four segments to this set of articles. One segment was meant to be published a week away and was or will be. Links to the other two–previously published– segments are below.

In addition, coming soon will be two related unpublished links on the favorite New York architect of his era, Stanford White.

https://classicchicagomagazine.com/daniel-hudson-burnham/

https://classicchicagomagazine.com/the-incandescent-john-wellborn-root/

Edited by Amana K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl