My 44 Years with John Porter

When you lose someone you’ve known for most of your life, memories flutter like pages in the wind. Mine drift in and out. I don’t think primarily in terms of numbers but when John Porter recently died, I realized I’d known him for 44 years.

I called on June 1st to wish him a happy birthday. I subsequently learned that the former North Shore congressman was in the hospital. I figured he’d be discharged within a few days, productive and fit as ever. He was gone by that Friday night, within hours of his 87th birthday. I was heartbroken. I had planned on telling him I would be in the nation’s capital in a few weeks. I wanted to schedule a reunion.

John Porter focused on the future, even when the future seemed grim. I know this because I met him in the 1970s. The context was the aftermath of a long, grisly war that had been bungled by the American government. For the first time in history, the President of the United States had resigned. In the 10th congressional district, the 1976 campaign resulted in one of the nation’s closest elections—a political philosophical pivot to the left. A candidate from Chicago’s south side defeated Republican

A couple of years later, I was in the back of the family station wagon turning from Green Bay Road onto Central Avenue in Evanston. We were going for Saturday morning breakfast at a favorite restaurant. As we turned, I noticed a Porter for Congress office on the corner. “Who is Porter?” No one knew. After breakfast, I asked my parents if I could go by the office. I was eleven years old.

When I stepped inside, I found and read one of John Edward Porter’s brochures. I learned that he’d attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—that he was a Republican, a lawyer and the son of a judge—and that he’d been elected to represent the North Shore in the Illinois General Assembly. John Porter looked serious in his pictures. He’d been born and raised in Evanston, attended Evanston Township High School and served in the Army reserves from 1958 until 1964. Candidate Porter opposed big government, whether mixing economics or religion with the state, and I knew enough to know that I agreed. John Porter struck me as the candidate for the future.

During that summer of ‘78, I rode my bike a couple of miles every day to Porter for Congress. One day, after weeks of volunteering for as many as 10 hours a day—stuffing envelopes, packing boxes, and loading Porter supporters’ cars with bumper stickers and signs known as “car tops”—the candidate walked in. Someone brought me to his attention. That was the day I met John Porter.

Porter for Congress and other campaign memorabilia

Credit: Photo by Scott Holleran

What impressed me foremost was his firm handshake and the seriousness with which he greeted me. He wasn’t condescending. He told me that he’d heard about a new kid volunteering, and he earnestly thanked me for my work. It wasn’t a long or deep conversation. But he was sincere. Later that summer, I had the opportunity to observe him in a different context at his home on Sheridan Road. He was relaxed, even playful. I remember that he displayed a dry sense of humor, which he didn’t filter for the sake of the children. I knew that I liked him.

The election night party was filled with anticipation. John Porter lost the 1978 campaign by 450 votes. He gave me a lesson in perseverance when, months later, he announced that he’d run again after the winning candidate was appointed as a judge. Again, I volunteered. Whether attending his back porch speeches, distributing pamphlets at train stations along Chicago’s North Shore—on platforms for the Chicago and North Western or the El in Wilmette, Evanston and Skokie—I can attest that the candidate never took a single vote for granted.

During one late summer afternoon conversation on a screened-in back porch in Glenview, I listened carefully as constituents asked deep questions. Extemporaneously, he spoke about guns, abortion, the military, the economy and a range of issues. I didn’t agree with all of his answers. But it was clear that he had thought about them. His responses were not canned. I remember raising my hand to ask a question that challenged one of his positions. He looked me in the eye and answered slowly and evenly, detailing with examples why he had reached a different conclusion. Later, when I privately expressed to him some equivocation, rather than placate me, John Porter continued the conversation. And he thanked me for challenging him.

That year, 1979, and, again, in 1980, when he was duly elected to Congress, where he served for 21 years, we went together from house to house and campaigned at various fairs, meeting at Gilson Park’s Wallace Bowl and community events. We shuttled about the district in the custom Porter for Congress van, where he was free to express himself, pause from the rigors of campaigning, drink water, eat a sandwich and catch up with his family.

John Edward Porter with his grandson, Jack Porter (photo courtesy of Robyn Porter)

John Porter was a decent, loyal and simple man. He was tall, handsome and commanding yet he was focused, slow to smile and he was purposeful. We celebrated victory at a Sheraton hotel in Northbrook after three consecutive years of nearly nonstop campaigning. A few years later, he called and asked me to consider coming to work for him on Capitol Hill for a paid internship. I knew it was an excellent opportunity. I accepted.

I worked in his office at the U.S. Capitol, serving as a messenger, answering phones and assisting aides in policy research. I researched and wrote constituent letters. As weeks passed in that frosty Washington winter of 1984, I realized that politics would not be my career. Every policy position came in the shade of nuance; every vote was taken in compromise or approximation. There’s more to the whole story, but my passion for politics froze in that single season.

John Porter never lost my respect. On the rare occasions I worked with him in Washington, I saw that he listened and welcomed varying views. He often took a position with which I strongly disagreed. But I could see why he’d reached a conclusion. John Porter was a measured and mindful legislator. We stayed in touch when I left, mostly through calls and Christmas cards. John was reelected that November with 77 percent of the vote.

Several years passed before we met again in Washington. By then, I’d moved out of Chicago and was writing for newspapers. I was the editor for a nonprofit patient advocacy organization in Southern California. I arrived at John’s office with the group’s ophthalmologist founder. We discussed a newly proposed method of health care financing called the Medical Savings Account. John Porter showed real interest in how I was doing. I was starting my writing and journalism career, reporting on new ideas and books as well as news and sports for publication. I told John that I thought writing, not politics, was the way to realize my ideals.

John pointed out that the catalyst for our meeting that day was political. His was a reminder that the American republic—based on individual rights—requires an explicitly political defense of the rights of man. John’s response was a magnanimous moment in which a mentor afforded both an opportunity and a lesson in front of my boss. John Porter was not a champion of capitalism in health care. But he voted to legalize the Medical Savings Account, which became law. Today, it’s known as a Health Savings Account. I know this because I have one.

That was the first of several intersections in which John’s work in the legislature aligned with my own. The friendship deepened. Later, when I visited D.C. with family following the Clinton impeachment of the late Nineties, John met us in his office and we took the underground ride to the Capitol. On the way, we ran into Sheila Jackson Lee, the Texas congresswoman who’d defended the president. Everyone was cordial.

I later launched a blog and invited John to be interviewed about his thoughts on science, medicine and vaccination. He accepted. He gave me an exclusive interview for an article in a suburban Chicago publication about President Kennedy’s assassination, recalling his appointment by the Eisenhower administration to work for the Department of Justice.

“What happens in that position is that you get a lot of responsibility,” he told me, recalling meeting Robert Kennedy, catching what he called Potomac fever and being shocked when the president was shot and killed in Dallas. “I was in the Evanston YMCA working out,” he remembered. “I felt tremendous sadness for his family and for the country. By then we had two boys and John-John [John F. Kennedy, Jr.] was about the same age as my son John.” He told me that he thought Lyndon Johnson may have been involved in assassinating the president.

That was quite an admission for a former congressman with a reputation for being tactful and discreet. I knew better; I never thought of John Porter as a buttoned-down establishmentarian and I didn’t treat him that way—I knew firsthand that he liked being challenged—and I have reason to think he grew to embrace going against the status quo. He invited me to attend the dedication of a National Institutes for Health (NIH) building named for him: the John Edward Porter Neuroscience Research Center in Maryland.

Looking back, whether I was passing out pamphlets in freezing temperatures at train stations, being asked to introduce him to New Trier Republicans next to Blann’s Pharmacy in Kenilworth or watching him debate an opponent at his alma mater, Northwestern University, working with John Porter was a pointed, formative and enduring part of my life. I waded through waist-deep flood waters at his Deerfield headquarters on Lake Cook Road to retrieve campaign documents, watched him on CBS Evening News, saw him defend Israel’s right to exist, debate gun control—one of his passionate causes—and forewarn against the welfare state. Once, before he was elected to Congress, I dropped by his downtown Evanston law office. John invited me in and offered a can of soda pop.

John later confided in me about summoning the courage to face his father after he decided to tell his dad—Judge Harry Porter—that he didn’t want to take over the family law practice after graduating from University of Michigan law school. We’d discussed his interest in exploring the philosophy of Ayn Rand—he read We the Living and had become interested in her philosophy, Objectivism—and we debated the proper role of government.

Though he fondly recalled from his early days attending an astronaut’s Washington parade, John always brought the focus back to justice. “I was assigned to review one case of a collision between a U.S. naval vessel and a commercial vessel in New York harbor,” he told me. “I recommended that the U.S. government not appeal because we were at fault.” In a 2017 letter to the editor of the Washington Post, he argued that America “was built on the pursuit of knowledge, in which teachers and students are free to expand their curiosity, study and evaluate issues, including controversial ones.”

My final talks with John came during the pandemic lockdown. He reached out, which was rare, and it was clear to me that John Porter was restless. He talked. I was happy to listen. John was reflective, contemplating his whole life. He had an idea—an idea for the future. I knew this meant that I had kept and earned his respect. That his idea didn’t come to be matters less than his continuing commitment to pursuing his own goals.

By then, he’d become a lobbyist—an advocate for funding scientific research—re-married the daughter of an Ohio congressman—Amy Porter, an NIH director, who survives him—and he told me he was happy to live in a home that had been the late Fox News and Detroit News journalist Tony Snow’s residence. During his life, John was recognized for advocating biological and medical research, including earning a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation “for [his] extraordinary efforts on behalf of medical research in pursuit of a cure for diabetes,” and support for neuroscience research.

John Porter with his daughter, Robyn Porter (photo courtesy of Robyn Porter)

Congressman Porter once told me that when he chose to get the polio vaccine, he knew that he “chose to break from the Christian Science belief that disease does not exist, that it can be overcome by prayer.” He had added with enthusiasm that he thought scientists were “on the cusp of personalizing medicine—that [someone would] soon discover the genetic basis for medical disease and that we will discover what will work for the individual on a personal basis.”

I challenged him: “Doesn’t that require capitalism?” John Edward Porter replied: “Yes.” I pressed on: “Are you saying that life is the standard of value—that scientific progress is measured by whether it’s reducible to enhancing a single, human life—like your father benefitting from the polio vaccine discovered by Dr. Jonas Salk?” He told me: “Yes…the whole point is to improve human life.”

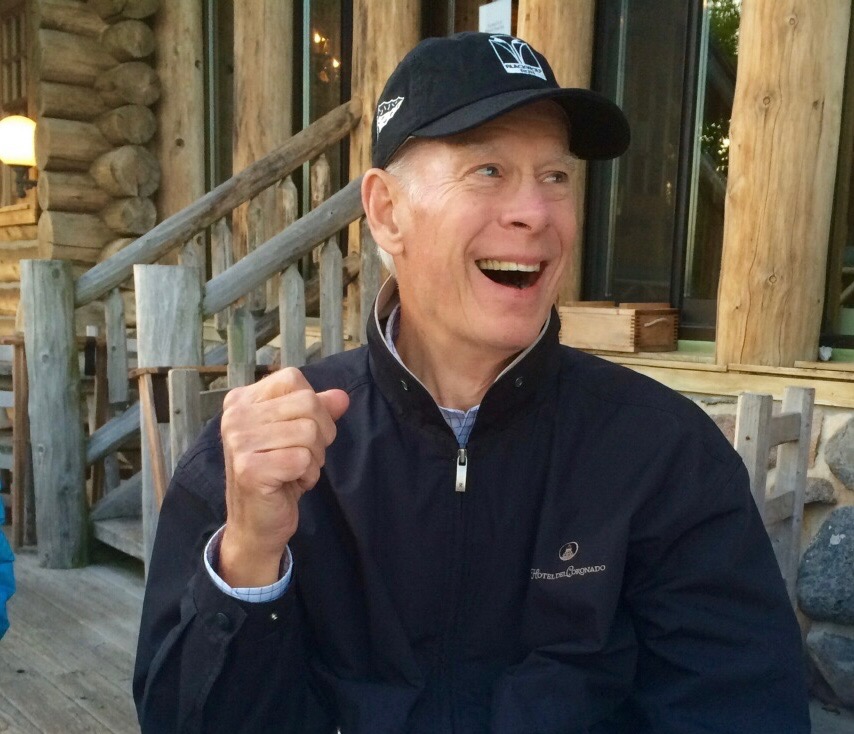

John Edward Porter celebrating his 80th birthday in Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of Robyn Porter

Memories and images waft into my mind—a staff dinner at Hackney’s, swapping out a ketchup-stained tie in the Porter for Congress van, his final making of a fist in solidarity with me—and I know that John Porter certainly enriched mine.

* * *

Former Chicagoan Scott Holleran, who volunteered and worked for Congressman Porter from 1978 until 1984, was recently awarded the Press Club’s Golden Quill for “excellence in written journalism.” Holleran’s writing has been published in the Los Angeles Times, Pittsburgh Quarterly, and The Advocate. Holleran lives in Southern California, where he’s writing his first novel.

Read and subscribe to his newsletter, Autonomia, at https://www.scottholleran.