The Drexel Boulevard Estate of Chauncey Justus Blair.

By Megan McKinney

We left the formidable Blair dynasty two weeks ago after a segment about Chauncey Buckley Blair and his brothers, Lyman and William—the threesome who established the great line in Chicago.

The generation that followed also produced a notable trio of men. Chauncey Justus, Henry Augustus and Watson Franklin were all sons of Chauncey and Caroline, whose only daughter, Harriet Olivia, became the wife of John Jay Borland. Harriet grew to be a prominent Chicago figure in her own right.

The middle son, Henry, born in 1852, married Grace Pearce in 1878 and their family—small for the time—consisted of two daughters, Natalie and Anita. They lived at 2735 Prairie Ave. and summered in Jefferson, New Hampshire.

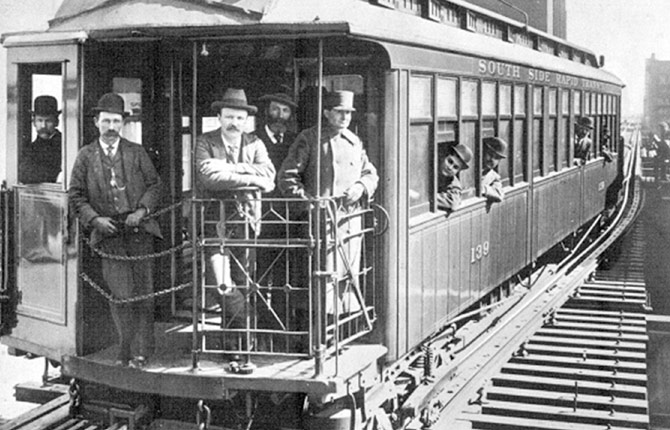

Henry was vice president of his father’s Merchants National Bank until it merged in 1902 with Corn Exchange National Bank. At about the same time, he turned his attention to consolidating Chicago’s numerous transportation lines into a single system and headed a syndicate of investors that bought Charles Yerkes’ elevated railway holdings. This was in early 1901 when the controversial traction baron gave up Chicago entirely to focus on building London’s rapid transit system. When consolidation was complete a decade later, Henry became a trustee of the resulting Chicago Elevated Railways Collateral Trust.

A train owned by the Chicago Elevated Railways Collateral Trust in 1911.

Henry lived long enough, barely, to become a resident of 209 E. Lake Shore Dr. The Benjamin Marshall apartment building, completed in1925 and now a cooperative, continues to be one of the city’s very finest.

When death came, Blair’s passing was marked by the synchronized stopping of every streetcar in Chicago for one minute at precisely 2 p.m. on February 23, 1932.

Henry’s brother, Watson followed him in birth by two years and, like Henry, was a product of the Williston School in Easthampton, Massachusetts. Watson dealt in beef and pork as a partner in Culbertson & Blair Packing and Provision Company, and later was a member of the grain commission firm Blair & Co., formed decades earlier by his father and ill-fated uncle, Lyman.

Watson joined other family members as a director of Merchants National Bank and its successor Corn Exchange National Bank; however, he was also deputy governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. In 1881, he married Alice Keep, a descendant of John and Sarah Keep who were citizens of Springfield, Massachusetts as early as 1676; Alice was also related to the Chicago Keeps, who had become well established in the city’s social circles. She bore four children, including the glamorous Wolcott, who will reappear as the central figure of two later segments in this series. The family lived at 720 Rush St.

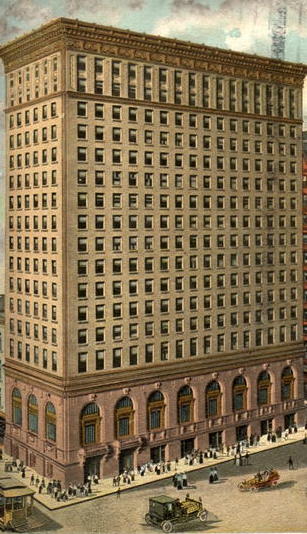

Corn Exchange National Bank, Adams and LaSalle Streets.

It was through Chauncey J. Blair, eldest son of Chauncey and Caroline, that the Blairs became linked with the banking Mitchells, another of Chicago’s eminent dynasties. William Hamilton Mitchell, patriarch of the formidable clan, was founder of the Illinois Trust and Savings Bank and, during three marriages, sired intriguing offspring who scattered about the nation and continent. The Mitchells will be thoroughly covered in a forthcoming Classic Chicago Dynasty series; however, discussion of one vibrant member of the clan and her progeny is appropriate here.

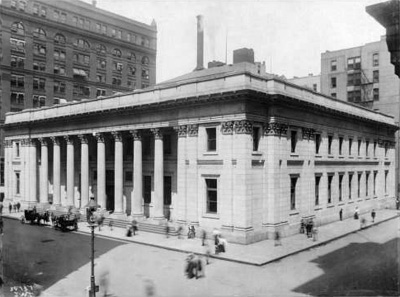

William Hamilton Mitchell’s Illinois Trust and Savings Bank at Quincy and LaSalle, was designed by Daniel Burnham in 1896.

In 1882, Chauncey J. Blair married Mary I. Mitchell, one of William’s many children. A world-class collector, Mary shopped the globe, especially Italy, where she acquired all the Roman silver excavated near Tivoli. She was reportedly the first Chicagoan to own Italian needlework and gold dinner service. Additionally, there was a valuable library of books she assembled and the city’s only collection of Gothic statuettes. But the display of her spoils wasn’t limited to Chicago; she also maintained an apartment in Paris filled with works of art and fine furniture. Although Mary relinquished 14 of her paintings for a quarter of a million dollars in a well-publicized sale to New York’s Kleinberger Galleries, she left an important group of medieval and Renaissance paintings and sculpture to the Art Institute in the Mary Mitchell Blair Collection.

At this point, the financial foundation of each of these two great lines had been secured through the industry and often courage of those who preceded current members. These qualities would reappear in descendants; however, we’ve reached a place in the progression of this joint dynasty where reporting on the activities of members swerves into the territory of vintage gossip, which can have its own interest. We’ll see.

According to Mrs. Carter Harrison II—wife of a five-term Chicago mayor, whose father had also been a five-term mayor—Mary Blair’s interests included a pair of pursuits that had nothing to do with collecting big-ticket items. She was an avid believer in the occult, and she enjoyed writing. According to the mayor’s wife, she managed to combine these activities by insisting she could write only under the dictation of a control, an invisible East Indian prince. Unfortunately, none of their joint works survive for us to judge.

Mary’s four children with Chauncey J. included Chauncey B. II, whose first wife, Mildred Marshall, sued him for divorce in early 1930—still a rarity for the day—and in May he married Paulette Whiting, becoming her third husband.

In December of the same year, his brother, the dashing William Mitchell Blair, went into voluntary bankruptcy. Two years later, William’s wife, Martha, daughter of the Alfred Hoyt Grangers of Lake Forest, sued him for divorce and began writing a Society column for Chicago’s Evening American—but not for long.

Cissy Patterson.

The following scenario soon made Martha one of her generation’s most visible of those carrying the Blair surname. Washington Times-Herald editor and publisher Cissy Patterson, a Chicago native, took notice of Martha’s column and invited her for a drink at the Tavern Club, with an offer to write for the Times-Herald. Although the columnist was a stranger to Washington, Cissy liked her style and thought she would be the person to write a similar column, to be titled These Charming People, for her paper.

Realizing that much of the “business” of Washington was conducted at evening social events, Cissy had assembled a group of attractive young women to cover the various receptions and dinners where government officials, politicians and diplomats gathered. Her alluring female columnists had become so evident around town that the group was known as Cissy’s Hen House, and Martha Blair quickly became its premier fixture.

Soon after moving from Lake Forest to D.C., Martha had begun a relationship with The New York Times Washington Bureau chief Arthur Krock. Her column, which was increasingly sprinkled with juicy political nuggets from Krock along with social chitchat, became de rigueur reading for Washington insiders. But after the couple married, the Times objected to their highly paid bureau chief passing on choice tidbits to another paper. The column quickly became relatively humdrum, and Cissy, in one of her fits of temper, killed it.

The powerful New York Times Washington Bureau chief Arthur Krock.

Typically, Cissy changed her mind within hours, but Martha rebelled, and, instead of returning to the Times-Herald, she began feeding items to Cissy’s archrival Eugene Meyer, publisher of the Washington Post. Eventually, the two ladies called a truce, and from then on, Martha confined herself to being Mrs. Arthur Krock.

However, These Charming People remained at the paper, written by Igor Cassini, for whom it was the first step in his career as the mid-century’s premier international society columnist, Cholly Knickerbocker. And one of Martha’s two sons, William Granger Blair, eventually followed the Krocks into the fourth estate as a reporter for The Kansas City Star and later The New York Times.

More vintage gossip: Chauncey J. and Mary’s daughter, Italia, gained instant notice when she was proclaimed “the most beautiful girl I have ever seen,” by visiting Italian actress Eleonora Duse. The two were introduced at a reception given by the former Rose Buckingham, wife of department store tycoon Harry Gordon Selfridge. Duse, who was then a global legend and widely regarded as one of the “greatest actresses of all time,” had seen many beautiful young women. Therefore, the comment created a reputation that was said to have “stuck to Italia ever after.”

How John Singer Sargent saw Eleonora Duse.

Italia went on to marry Spanish nobleman Ricardo de Soriana and become the Marquise d’Ivernay of Madrid, Spain. There was another daughter, Mildred, who married Henry B. Farr but died within a few years.

As mentioned earlier, Chauncey B. and Caroline Blair’s only daughter, Harriet Olivia, married John Jay Borland in 1878. Their two sons were Chauncey Blair Borland, born later that year, and Bruce Borland in 1880.

John Jay Borland—who died in 1881 at age 44—was like so many 19th century Chicago patriarchs, a Yankee—and one of very long standing; his ancestors had emigrated from Scotland to Boston in the 17th century. He had been born in New York State in 1837; however, his father, a lumber merchant, brought the family to Chicago by way of Wisconsin in the mid-19th century. Although John Jay continued operating the lumber firm Borland and Dean, he began investing in land and soon had become a prominent commercial real estate developer.

Although Harriet Blair Borland’s gender kept her from the banking career of her brothers, she made a reputation in Chicago with philanthropy and art collecting that survives today.

Angel lectern.

In 1894, Harriet gave an angel lectern to Trinity Episcopal Church at 26th Street and Michigan Avenue; it bears the added cache of having been designed for the World’s Columbian Exposition the year before.

Her philanthropy extended to Rush Medical College, which continues to benefit from her generosity in the endowment of the Harriet Blair Borland Professorship in the Department of Pathology.

Also gaining from Harriet’s largesse is the Art Institute, which received paintings from the estate of her son Bruce at his death in 1961. In the collection, which passed to him when she died in 1933, was this Claude Monet oil on canvas, painted in 1895 of Sandvika, a village near Christiania, now Oslo, and, below it, the Camille Pissarro oil on canvas Haymaking at Éragny, 1892.

Claude Monet oil on canvas, Sandvika, Norway, 1895.

Camille Pissarro oil on canvas Haymaking at Éragny, 1892.

Megan McKinney’s series on The Blairs will continue in a future issue of Classic Chicago with The Edward Tyler Blairs.

For previous articles in this or other Classic Chicago Dynasty series, click:

https://classicchicagomagazine.com/category/vintage/classic-chicago-dynasties/

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl