BY MILOS STEHLIK AND ELIZABETH NAJDA

The medical clinic is busier than usual, filled with those who are not used to Telluride’s elevation of 8,750 feet, just as the annual Telluride Film Festival, now in its 45th year, unveils its highly selective roster of films. The four-day festival is simply the best film festival in the world.

The official festival begins when the main street, Colorado Avenue, is blocked off with food and drink for pass holders in the opening night “feed.”

Telluride.

The homegrown film festival.

What makes it special is the combination of new and old, of the lack of “business” and hustle, which permeates other festivals like Cannes or Toronto. Telluride means standing in line at an outdoor coffee kiosk behind Ralph Fiennes and the young Ukrainian dancer who is the star of the Fiennes-directed biopic of Rudolph Nureyev, The White Crow.

It means being the first to see films that might well be big contenders in the fall awards season leading up to the Academy Awards, like this year’s astonishing Roma by Alfonso Cuaron (Gravity), the very personal portrait of a middle-class Mexican family seen through the eyes of an indigenous maid. It may mean being the first to see Jason Reitman’s The Front Runner—a truly brilliant take on Gary Hart’s presidential campaign, which short-circuited with revelations of his affair—or The Favourite, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos and focused on palace intrigue in the 18th century court of Queen Anne. Emma Stone, Rachel Weisz, and Olivia Colman form the lesbian love triangle at the film’s center.

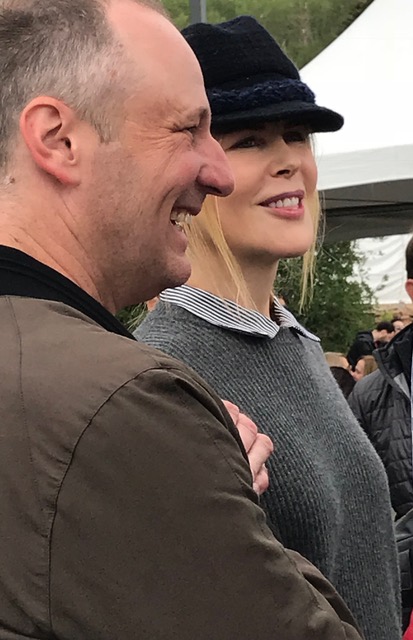

Nicole Kidman at Telluride.

Emma Stone, who received one of the Festival’s special tributes, was there, as was Nicole Kidman (appearing in two films) and Robert Redford, who plays an aging, but smiling, bank robber in The Old Man and the Gun, acting alongside with Casey Affleck and Sissy Spacek.

The Festival’s first screening was devoted to Charles Ferguson’s Watergate – Or: How We Learned to Stop an Out of Control President. At four-and-a-half hours, this recap of history many still remember is nothing short of riveting and eerily contemporary. Werner Herzog, a filmmaker known for his daring films like Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo, both of which are set in the Amazon, turned his camera on Gorbachev in his film of the same name featuring conversations with the aging and ailing former leader of the Soviet Union who, unquestionably, changed the world.

Werner Herzog meeting Gorbachev.

Rithy Panh.

A second Telluride Silver Medallion went to a filmmaker whom everyone should know: Rithy Panh. As a child in Cambodia whose parents and siblings all perished during the Cambodian genocide Panh nearly starved to death in a work camp under the most brutal conditions. These experiences form the body of his now numerous films and books, becoming a witness to history and an agent of reconciliation. In his spine-chilling documentary S 421, he brings a guard at the notorious Khmer Rouge camp face-to-face with one of his victims. In Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell, Panh confronts his audience with the infamous leader of the Khmer Rouge, and in The Missing Picture, brilliantly uses clay figurines to tell the story of his family, his own survival, and eventual escape to Thailand and France, where he now lives.

It took forty-eight years to bring Orson Welles’s unfinished last film, The Other Side of the Film, to the screen. Now reconstructed according to Welles’s notes and unfinished edits through the Herculean efforts of Frank Marshall, the film, which most people thought would never see the light of a projector, finally premiered at Telluride. John Huston plays the director of a film-within-a-film, seemingly channeling Welles in his trenchant and sometimes cynical observations on the state of the film industry and the difficulty of artists trying to survive within it. Dense and filled with brilliant imagery and all-too-much dialogue, the film is, as Hollywood Reporter chief film critic Todd McCarthy observed on a panel discussion following the screening, Welles’s version of Finnegan’s Wake.

The wonder of Telluride is that it is a true celebration of cinema. A guest director is chosen each year to select six films. This year the selections of novelist Jonathan Lethem included two wondrous Ernst Lubitsch films, Angel (1937) and the 1942 classic To Be Or Not To Be, along with Douglas Sirlk’s Tarnished Angels and Nicolas Ray’s Bigger Than Life.

Paolo Cherchi Usai and his wife, Renata, who were married at Telluride.

Paolo Cherchi Usai, the chief curator of one of the world’s great film archives, Eastman House in Rochester, New York, and co-director of the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy brings a selection from the Pordenone Festival to Telluride. This time there were two rare silent French films: Coueur Fidele by Jean Epstein and Fievre by Louis Delluc, with accompaniment by the percussion-based Alloy Orchestra, and a true miracle of a discovery: Christian Wahnschaffe, made in 1920 by Urban Gad, the Danish-born director who discovered (and married) silent film star Asta Nielsen, who played the first female Hamlet in a 1921 film. The film is a revelation. In it, Gad tells the story of the son of a wealthy family, who is unhappy with the trappings of his family’s life and longs for something “real.” He finds it in a poverty-stricken quarter of Berlin where he gives his money away in a quest to buy peace and happiness.

Christian Wahnschaffe.

Stephen Horne, a musician for the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy, played the piano, accordion, and percussion instruments in a brilliant musical accompaniment. At the conclusion of the film, as the main character, attacked by a small mob, is stripped bare, and we see his body against a wall, arms outstretched as if he were being crucified, the audience at the Telluride Film Festival screening stood up and gave Horne (and the film) a thunderous standing ovation. Almost a hundred years after it was made, the film had the power to move hearts and mountains.