The Story of Baymeath

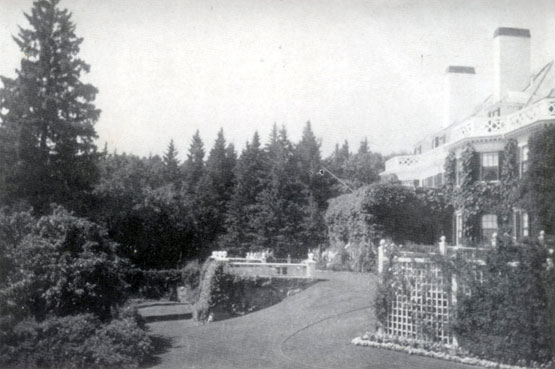

Baymeath, the Bowen house in Bar Harbor as it looked when finished.

By Megan McKinney

Editors Note: Information and photography for this article are courtesy of Brad Emerson, The Downeast Dilettante, https://thedowneastdilettante.blogspot.com/2011/03/three-more-degrees-and-were-done.html

Louise and Joseph Bowen had been in their Astor Street house for only four years when they decided in 1895 to build a modest summer home in Bar Harbor. This was after several seasons of renting cottages and becoming attached to the community.

The couple began by acquiring a lovely piece of farmland with meadows sloping to the shore at Hulls Cove on property with spectacular views of the Mount Desert Hills. The architect they engaged, Herbert Jacques of the fashionable Boston firm Andrews, Jacques & Rantoul, summered in Bar Harbor, making him an excellent choice to design a house appropriate to the setting.

Another view of the completed house.

The task was to construct a low, modest building to blend with the landscape. However, by the time requirements were considered—rooms for the adult Bowens, their four children, with nurses and governesses, houseguests, and necessary maids and cooks—it became apparent that the house would be neither low nor modest. Thirty-five rooms—including 19 bedrooms—would be required for family, staff and guests.

Looking up the slope to the house.

Hidden from general view, the main house was approached by a curving road that wound up a hill through a double stand of maple trees to its stone gates, beyond which Baymeath stood surrounded by soft green lawns and great beds of shrubbery. A description of the completed design was “a fusion of French and Colonial styles, with the steep roofs of a château, but detailed in 18th century American style.” That was merely the house.

An aerial view of Baymeath’s main house, all 35 rooms of it.

.

Soon the lovely piece of farmland with sloping meadows had expanded to an estate with wide-ranging gardens, indoor and outdoor swimming pools, greenhouses and a teahouse. Then there were charming cottages for the gardener and head butler, plus a large stable and a coach house. The coach house, which was not as simple as one might imagine, also contained extensive staff quarters and was known as “the Greek temple.”

The gardener’s cottage.

As the scope of the property increased, so did the need for people to maintain it—40 in all. The head gardener, who lived amid blooms and blossoms in a cottage at the gate, was a Scotsman trained in England. He was backed up by a half dozen assistants who maintained not simply the spacious formal gardens but also the wild garden, the greenhouses and cutting and kitchen gardens in standout condition.

A sample of the Scottish gardener’s work.

The stables—which would become garages—required an on-site workforce. In the early days, these included grooms and coachmen, “who wore elegant liveries that were as expensive as Paris gowns,” not to mention stable hands to care for horses, which were transported in by train, then across to the island every summer.

The housekeeper, cook, scullery maids and chambermaids lived in 10 bedrooms on the second floor in the service wing—envision some of the frequent servants’ quarters scenes in Downton Abbey—and then there were nurses and governesses, who were housed closer to their charges.

The view from the house down to the outdoor pool.

This somewhat unseen support system of servants sustained a life that was lovely; perhaps it was not the simple life Louise had envisioned at the outset, but lovely. There were the quiet summer activities of tennis and croquet, garden parties, sailing and dancing; however, house parties brought guests for days, even weeks, at a time. These visitors required entertainment and Louise’s parties were given for up to 200 guests.

The entrance and front hallway in Louise’s day, with cozy, rather than sumptuous, décor.

Tastes change. Above was Louise’s interior during Baymeath’s heyday. In 1941, when she was in her 80s and a longtime widow, with World War II and “the servant problem” looming, Louise realized that she must sell Baymeath, which she did to a family of aristocratic Belgian refugees. We don’t have a record of what they did with the interior. It was wartime; therefore probably very little.

However, everything would change with the arrival of Edith Pulitzer Moore.

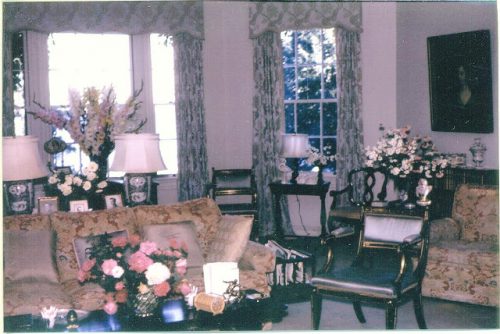

Edith Moore’s Baymeath drawing room.

In 1948, with the war—if not the servant problem—well over, Edith Pulitzer Moore became chatelaine of Baymeath. The daughter of newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer had grown up with summers at Chatwold, the nearby estate of her parents. And she later vacationed with her husband, William Scoville Moore, at their summer place, Woodlands.

Another look at Edith Moore’s transformation of the Baymeath interior.

When Woodlands was destroyed by the fires that swept Mount Desert Island and much of Maine in 1947, Edith, by then a widow, purchased Baymeath. And she redecorated.

It was not the house of the Bowens, nor would it ever be again.

Photo Credit : Brad Emerson

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl