BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

“Parks should be open and available to everyone,” says DeDe Petri, the first president and CEO of the National Association of Olmsted Parks. “That was not the case when Frederick Law Olmsted first brought public parks to the urban landscape. He was less of a landscape architect than someone who wished to restore a sense of civility and advance the democratic experience for all. His designs were beautiful and restorative, but we honor him this year more for his expansive plans to bring the country together outdoors.”

This year, Olmsted 200 celebrates the birth of the founder of American landscape architecture and profound social reformer, with Chicago; Lake Geneva, Wisconsin; and Riverside, Illinois, serving as Midwestern celebration sites recognizing the genius of the man best known for creating New York City’s Central Park. Frederick Law Olmsted and his son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., also played a significant role in establishing and creating our country’s national parks.

Petri has traveled across the country to lecture on Olmsted, brought other experts to the table, and planned a variety of virtual programming. Following a summer presentation to a full house in Lake Geneva, Petri shared, “Olmsted designed the American landscape. In the Midwest, you are living with this legacy. Because he designed Central Park, he is thought to belong to the East Coast, but that is definitely not the case. He came to Chicago in 1871 with Calvert Vaux to design the South Parks plan, with the upper park being Washington Park and the lower, connected by the Midway Plaisance, being Jackson Park. It was a beautiful plan, but with the Chicago Fire, it was put on hold.

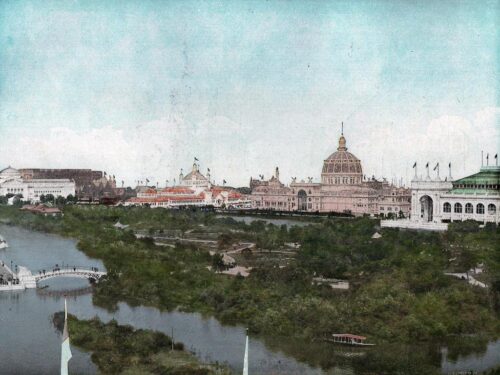

“There was then a little work done then in Washington Park but not by them,” she adds. “He returned in 1892 to work on the World’s Fair, which opened a year later.”

To Petri, previously the 42nd president of The Garden Club of America, Olmsted’s greatest accomplishment for the World’s Fair was to “soften the White City” by adding places such as the Wooded Island, water features, boating experiences, and scores of plantings: “He was really up against the clock, getting it ready to go,” she explains. “He scoured the Wisconsin and Illinois countryside and brought in over a million plants to line the sides of the vast lagoons.”

Olmsted was 70 at the time of the World’s Fair and Petri feels that his lifetime of experience contributed to the beauty he created: “His life was very exciting, and he learned from every experience. He travelled coast to coast, down the Mississippi, and had amazingly diverse experiences.”

He sampled various careers including merchant, apprentice seaman, experimental farmer, author, and even gold mine manager. He directed the United States Sanitary Commission, which was the forerunner of the American Red Cross, and wrote for the New York Daily Times, where he exposed the injustice of slavery, all before he created Central Park

While in Lake Geneva, Petri recognized the significant efforts of the Yerkes Future Foundation, working to preserve not only the historically significant buildings of the 1897 Yerkes Observatory (whose ownership was transferred to the Yerkes Future Foundation by the University of Chicago in 2018), but also to authentically recreate the 48 acres of Olmsted-designed grounds surrounding them.

Members of the Lake Geneva Garden Club have been directly involved with these landscaping plans. According to legend, Albert Einstein asked to see just two places during his first visit to the United States in 1921: Niagara Falls and the Yerkes Observatory.

Olmsted also became involved with the Glessners, explains William Tyre, Executive Director and Curator of Glessner House in Chicago: “The Glessner and Olmsted families formed a close friendship after they were introduced by our architect Henry Hobson Richardson in 1885. Olmsted was a frequent visitor to the Glessners’ winter and summer homes in Chicago and New Hampshire, respectively, and advised on the landscaping of the latter, known as The Rocks.

“His son, Frederick Jr., known as Rick, was the best friend of the Glessners’ son George during their years together at Harvard in the early 1890s, and Mrs. Olmsted referred to George as their ‘adopted son.’ Rick and his brother John formed Olmsted Brothers after their father’s passing and continued to provide landscaping design services at The Rocks for decades.”

In Riverside, Olmsted took on the design of an entire town in 1869. Architect Charles Pipal, Chair of the Riverside Preservation Commission and an adjunct professor at the School of the Art Institute, shares, “As in his earlier park work, he was quick to assess those aspects of the existing site, which he could utilize and even enhance in his design. In Riverside that was specifically the changes in elevation, both subtle and dramatic, existing stands of native trees, and its proximity to Chicago via convenient rail link.

“The key aspects of his plan of 1869 were the curvilinear streets, in stark contrast to Chicago’s unforgiving grid, which followed the existing natural topography; the design of picturesque public spaces, including two large ‘commons’ and the Swan Pond along the Des Plaines River; and layered, naturalistic plantings. All of these were fully employed to given the residents and visitors the impression that they were visiting a park, where one yard visually flowed freely, without fences, to the next.”

Olmsted himself summed up his efforts in 1893 to Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer: “The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery … and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to the power of scenery.”

Visiting any of his outdoor spaces, it is hard not to feel deeply the impact of the scenery around you.

To learn more about the multiple celebrations of Olmsted’s life, visit olmsted200.org.