By Megan McKinney

Chicago’s North Side was a dense, muddy forest in the 1830s.

It was real estate investment that took 30-year-old William Butler Ogden out to Chicago from his native New York State in 1835. And it was real estate investment that kept him there—after initial misgivings.

When the Chicago Potawatomi population signed a treaty relinquishing the last of its Illinois land to the federal government and moved west in 1833, it was in effect the birth of Chicago. Almost immediately, a buzz surrounding the skyrocketing value of its “canal lots,” described in an earlier segment, reached the ears of Eastern speculators. And among the Yankees who made an early investment was Charles Butler, brother-in-law of William Ogden, whom he sent out to Chicago as his representative.

After slogging about the muddy quagmire that his sister Eliza’s husband had bought—sight unseen—for $100,000, Ogden wrote that the investment had been the “grossest folly.” This tract included much of the land from Chicago Avenue south to the Chicago River between LaSalle Street and what is now North Michigan Avenue.

A few months later, when he sold one-third of the land for more than the original cost of the parcel, Ogden revised his appraisal and resigned his position as a New York state senator to relocate in the developing community of the 1830s. His persistence, enterprise and single-minded determination created the first legacy of great wealth that continues to be enjoyed by Chicago’s 21st century heirs. He invested heavily in real estate and also acted as agent for Eastern investment partners and clients who wished to direct excess capital for the purchase of Chicago land. Following one term as mayor—Chicago’s first—he continued to serve regularly as alderman, recognizing that, to protect his investments, it was necessary to be active in local government. Ogden continually campaigned for city taxes to pay for streets, sidewalks and other vital infrastructure, and, when unsuccessful, he raised the monies himself.

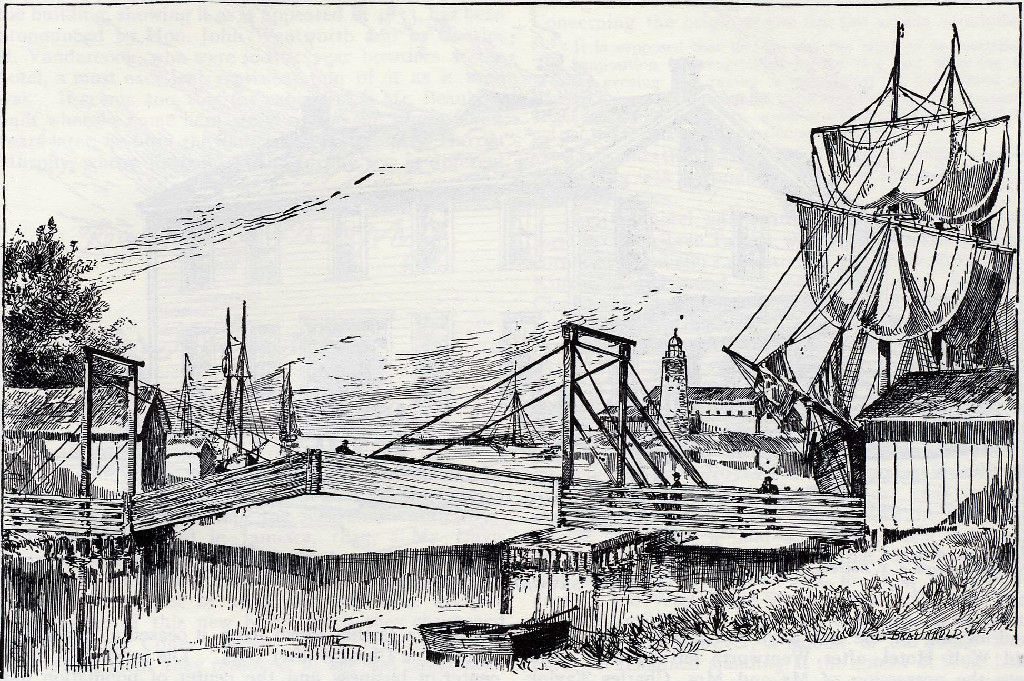

Ogden and a prominent neighbor were creative in raising funds to replace this bridge.

An example of Ogden’s proactive approach to the development of Chicago was the original Clark Street Bridge. The first structure crossing the Chicago River had been a drawbridge at Dearborn Street, which was operated by chains and chronically stuck. When the bridge was mercifully swept away by a storm in 1839, residents south of the river resisted spending money for a new one.

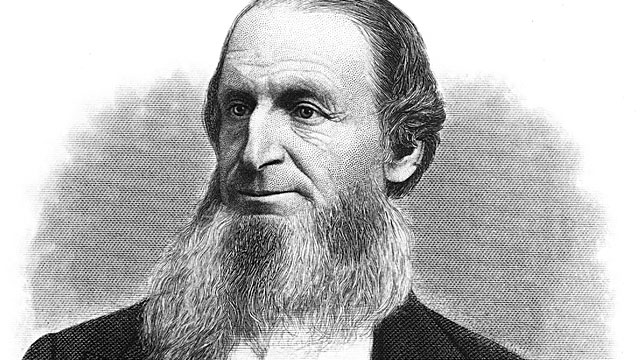

Bust of Walter Loomis Newberry in the library he endowed.

In order to gain Catholic support for construction of a new bridge at Clark Street, Ogden and his friend Walter Loomis Newberry, both North Siders, donated the block between State and Wabash, Chicago and Superior, for Holy Name Church.

When passing by this historic cathedral, remember the source of land on which it sits and why it is there.

In 1836, when it was time to build a house for himself, his mother and a sister, the bachelor Ogden summoned New York architect John M. Van Osdel, who designed Ogden Grove, a large Greek Revival-style residence with a rooftop observatory on four acres of North Side land bounded by Wabash and Rush, Erie and Ontario. An avid admirer of horticulture, Ogden hired a European gardener to cultivate his grounds and installed a glass conservatory in back of the house.

In conforming to a pattern being set in this new North Side residential area, Ogden carefully drained the swamp and cleared away underbrush, but kept the existing elms, maples, poplars and ash trees. He brought in wild and ornamental shrubbery from the Calumet Lake area and planted Virginia creepers, dogwood, Carolina roses and bittersweet. Because the trees were kept, it appeared from a distance that forest still existed throughout the area; however, where swamp and thickets of scrub had been, there was now careful cultivation. And tidy paths of gravel wound throughout Ogden’s garden and grounds.

Architect John M. Van Osdel.

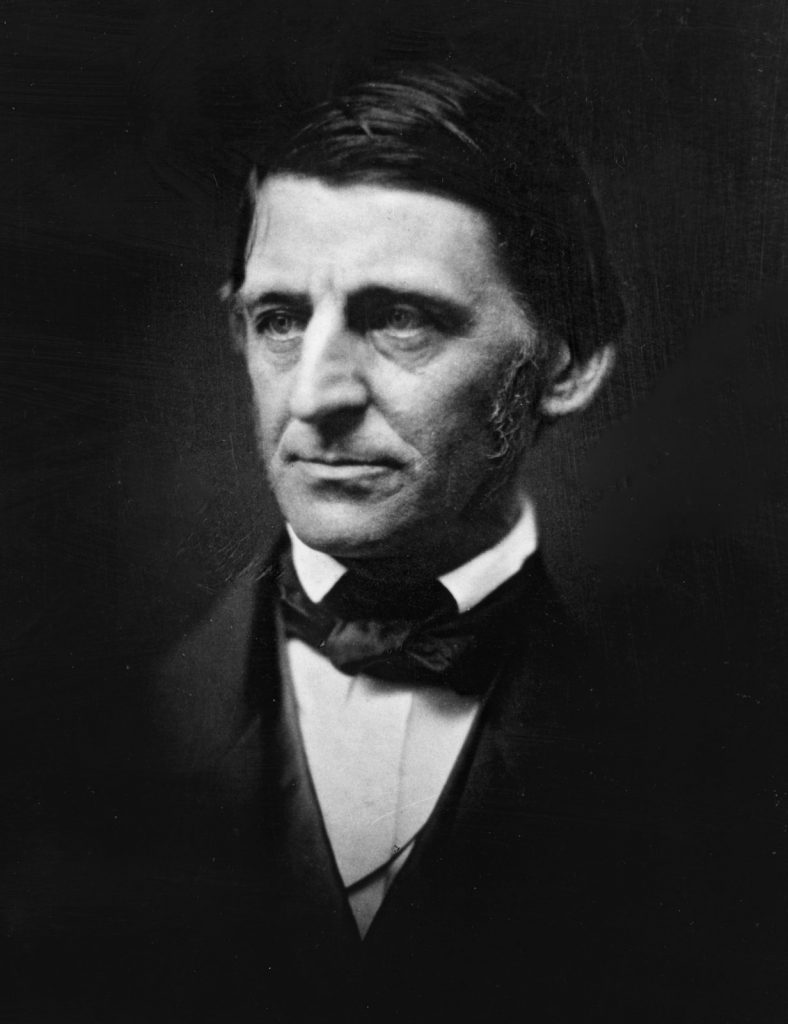

The mansion quickly became early Chicago’s social center, with the handsome, convivial Ogden serving as a hospitable host who threw large parties in which he entertained guests with tales of his youth in New York State and sing-alongs in the parlor to his piano accompaniment. VIPs visiting Chicago invariably stayed at the Ogden estate and notable guests included William Cullen Bryant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Samuel Tilden, Martin Van Buren and Daniel Webster.

Ralph Waldo Emerson.

By 1871, Ogden’s business interests were keeping him in New York for much of the time; he was at Villa Boscobel, his estate at the northern edge of Manhattan, when he learned that fire had destroyed the city he had been so instrumental in building. Hearing the news, he left immediately by express train to return to the desolate city. While picking his way through the ruins, he arrived at his own house. “I came to the ruined trees and broken basement wall,” he later said, “all that remained of my more than thirty years pleasant home.”

Ogden’s brother, Mahlon Dickerson Ogden, also an attorney, suffered great losses in the Fire, but had much better luck with his home. In the late 1850s, he had built an imposing house on Walton between Dearborn and Clark Streets. Although the solid three-story, brick, mansard-roofed structure stood directly in the path of the Fire, it was the only such building to survive, remaining on the spot for several decades until it was razed to make way for the massive Henry Ives Cobb-designed Romanesque Newberry Library.

Mahlon Dickerson Ogden’s house, which miraculously survived the Great Fire of 1871, but was demolished to create space for the Newberry Library.

William Butler Ogden was a public-spirited citizen, whose pro bono activities went beyond the generous contributions of money he donated to the city’s charitable and cultural organizations. Among the institutions he founded, with peers, were the Chicago Historical Society, the old University of Chicago—where Ogden served as president of the board of trustees—Rush Medical College, Northwestern University and the esteemed Chicago Relief and Aid Society. The last was for many years the city’s premier charitable and humanitarian organization and one that conferred great social cache upon its supporters.

Among Ogden’s financial interests were a steamboat company, a brewery and hundreds of thousands of acres of Wisconsin pineland with their accompanying sawmills. Known as the “Railroad King of the West,” he built his earliest rail line in 1848 and little more than two decades later had become Union Pacific’s first president. He also financed several banks and, at one time, was partner with Cyrus Hall McCormick in his Reaper Works.

William Ogden at what was then very old age (seventyish).

But Ogden’s great love was real estate, and among his holdings was The Sands, a large parcel of then notorious land along Lake Michigan north of the Chicago River, which he purchased with the aid of his attorney, Abraham Lincoln, and cleared of its riffraff. During the past decades, this southern portion of Streeterville—created in 1857 as Chicago Dock & Canal and reorganized as a real estate trust in 1962–has been the site of some of the city’s most dynamic development, further increasing the wealth of Ogden heirs.

The childless William left an estate valued at $10 million in the economy of 1877, including monies that funded the graduate school of science at the University of Chicago. He bequeathed his assets, including a generous chunk of Chicago Dock & Canal to a niece, Eleanor Wheeler.

Next in Megan McKinney’s story of Chicago’s first Classic Dynasty is the tale of what happened to what may be Chicago’s greatest existing inherited fortune.

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl