By Megan McKinney

Cloud Gate, Chicago’s beloved “Bean,” an international favorite in the city’s handsome Millennial Park.

In 1890, a few days after A. Montgomery Ward, George R. Thorne, their retinue of vice presidents and a civilian army of white-collar workers moved into the new Montgomery Ward building at 6 N. Michigan Ave., Ward stood in his office window, looking across the avenue toward the park. There was a beautiful blue lake out there, but he could scarcely see it. Nor did he see trees, grass, green shrubs or flowering bushes. What he did see were livery stables, squatters’ shacks and a few other unsightly buildings, along with heaps of tin cans, mounds of ashes and other rubble.

The Montgomery Ward Building, center, on Michigan Avenue at Madison Street.

Ward had hired architect Richard E. Schmidt to design a building to line up on the west side of the avenue with other distinguished corporate headquarters housing Chicago’s great companies—it was an elegant stretch, a proud parade of the city’s commerce. On the other side, in Ward’s words, was “a shabby dumping ground.”

Back in 1836, when public officials were platting land to be sold to pay for the Illinois and Michigan Canal, they decided not to let go of the stretch of space next to the lake. Instead, the lakefront portion of the three-year-old village, from Randolph Street south to Park Row, was deeded a public square to “Remain Forever Open, Clear and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstructions Whatever.” That changed somewhat with the Fire of 1871 when debris from the conflagration was pushed across the space, expanding its borders into the lake, and eventually flattening the enlarged area into smooth terrain. Other parks have blossomed on landfill, but not this.

In 1844, the “public square” of 1836 received a name, Lake Park. The space was extended in 1852 by rails on a causeway built offshore by the Illinois Central Railroad and separated from the park for a time with a stagnant lagoon. Temporary intrusions—such as the white tents above for Civil War veterans celebrating an 1890s reunion or troops camping during the Pullman Strike—came and went.

Ward believed, and believed strongly, that Lake Park should be restored to what it was meant to be, a lovely green public park with grass, flowers, walks, benches and trees, a place where workers could stroll during lunch hour. Someone should have taken steps to clear the area long ago, yet nobody had; the Fire had been past for nearly two decades, and the condition of the area was becoming worse. It was then Ward knew that if there were to be a change, it would be he who must make it. He immediately contacted his lawyer and good friend George Merrick.

“Merrick,” he was heard to bark, “this is a damned shame! Go and do something about it.” And Merrick did. He rounded up an expensive team of lawyers, paid by Ward, to begin a series of legal battles that would stretch on for more than another 20 years. It should not have been difficult; Ward simply wanted the city to enforce the original dedication of the park for public use, “Forever Open, Clear and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstructions Whatever.”

But it did become difficult, and, as the last decade of the century progressed, many of Chicago’s powerful businessmen wanted to erect buildings in the space. The first suit began in 1890 and continued for seven years and thousands of dollars until the Illinois Supreme Court agreed in Ward’s favor in 1897, and the property was cleared.

“Without recourse to the courts,” Ward said, “there would be merry-go-rounds and whatnots all the way to Park Row. They have made a dumping ground of the park, allowed circuses, masked balls and anything else there.”

But it wasn’t over and the cost to Ward was not merely money; he was scorned by many in Chicago’s business community, who accused him of stopping progress. The Chicago Tribune, which lined up on the side of the businessmen, described him as “a human icicle, shunning and shunned.” Victor Lawson also steered his Chicago Daily News against Ward, ordering his employees to “destroy” the park in print, declaring, “The lake front should be used to produce revenues for the city.” But Ward carried on.

When the Illinois National Guard wanted to construct an armory in the park, the legal process began all over again, also winding up in a Supreme Court decision in Ward’s favor. This was followed by a third suit and a fourth—each time working through lower courts and on up to the state’s highest. There was but one building Ward allowed to remain.

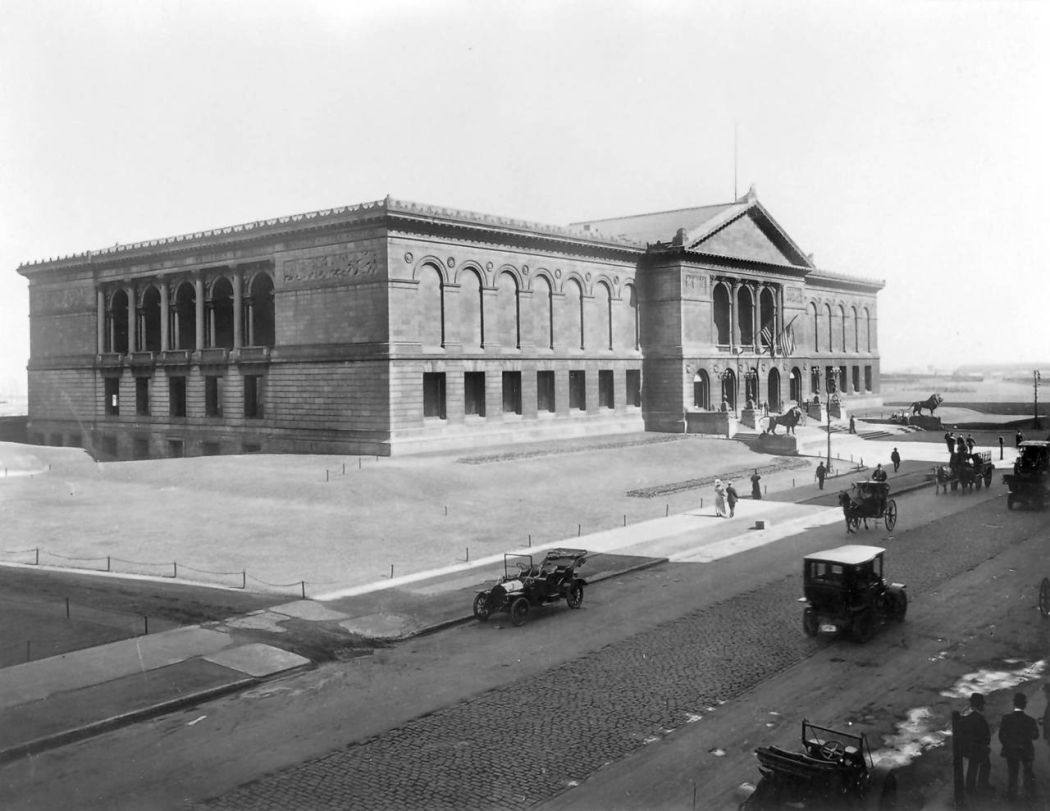

The Art Institute was designed by the Boston firm Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge in 1893. Look closely, Edward Kemeys’ lions—recast in bronze from their original plaster White City version—were on guard from the beginning.

Montgomery Ward’s great personal legacy to each of us is breathing space and natural beauty. It was only he who recognized that the city’s richest asset was the lake, and the time to preserve Chicago’s unique advantage was not after massive industry had forever cluttered the glorious curving shore, along with its fine white sand and clear water. Ward’s amazing tenacity in fighting the commercial and industrial development of the lakefront is and always will be a great gift to all Chicagoans and those who visit the city.

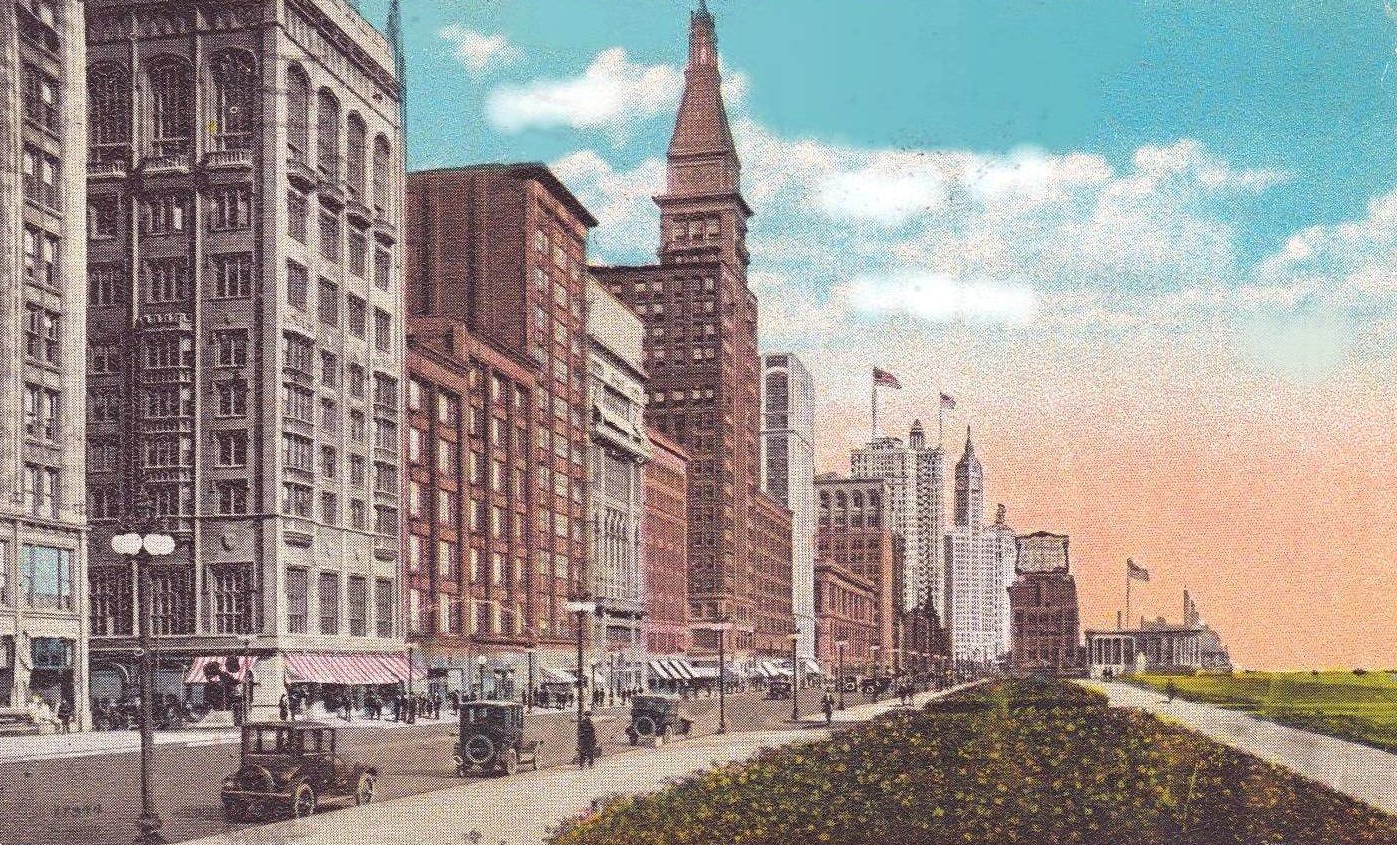

“Chicago’s Front Yard” in 1925.

The only newspaper interview ever granted by A. Montgomery Ward was to a reporter from the Chicago Tribune in 1909, four years before his death. “Had I known in 1890 how long it would take me to preserve a park for the people against their will, I doubt if I would have undertaken it…I fought for the poor people of Chicago—not the millionaires.” He added, “Perhaps I may yet see the public appreciate my effort. But I doubt it.”

The Aon Center on Randolph Street.

Nearly a century later, on the second anniversary of our celebrated Millennium Park, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lois Wille wrote in the Chicago Tribune of a 1997 encounter between Mayor Richard M. Daley and the late “civic leader extraordinaire” Sara Lee chief executive John Bryan at a reception on the 80th floor of the Aon Center. The impromptu meeting between the mayor and the great pro bono fundraiser lasted but a few minutes; however, those few minutes sparked the creation of the magnificent 21st century park that is the gem of modern Chicago.

“Daley asked Bryan to look out the window,” Lois Wille wrote, “To the left was Lake Michigan, the right was the stately Michigan Avenue skyline. Glorious, both of them. But directly below, south of the Randolph viaduct, lay a muddy pit littered with remnants of a railyard, discarded machinery, a few parked cars, even some old railroad cars. ‘We should build a park there,’ the mayor said.”

Would it surprise you to read that Lois Wille’s next paragraph began, “It turned out to be the best thing that has happened to Chicago’s downtown lakefront since the day in 1890 when Aaron Montgomery Ward looked out the window of his new office tower at 6 N. Michigan Ave.”?

She continued, “Daley and Bryan, helped by the brains and cash of a host of other Chicagoans, put together the exuberant mix of art, architecture, gardens and theater that is Grant Park’s northern neighbor. Millennium Park.”

Don’t fret, Monty, it’s not a building; it’s a work of art

The Montgomery Ward series within Great Chicago Fortunes will continue next with Montgomery Ward and the Thorne Rooms.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl