Mason Phelps’ 116-Year-Old Olympic Golf Memento Stays in the Family

By David A. F. Sweet

Winning an Olympic medal is rare — but winning one in golf is rarer still.

Though the sport is far more popular worldwide than other Olympic perennials — modern pentathlon, anyone? — golf has been contested in the Olympics only three times. And for Chicago golfers, it’s the 1904 event — rather than the ones in 1900 or 2016 – that garners tremendous interest.

A 10-man Western Golf Association team traveled by train to St. Louis, which held the Summer Games for its first and only time. Though players from only two nations, the United States and Canada, competed at the Glen Echo Country Club — the jaunt from Europe to the American Midwest was considered too far by top international players — nearly 80 golfers competed that September. Led by captain Chandler Egan of Exmoor Country Club, who had won the U.S. Amateur that year, the Western Golf Association team captured the gold medal after 36 holes of play, topping the Trans-Mississippi Golf Association team and the United States Golf Association team.

Mason Phelps (right) and Paul Hunter were both excellent golfers early in the 20th century.

According to Don Holton, the golf historian at Exmoor, “the players battled high winds, which grew stronger throughout the day, and the WGA led by only two strokes after the morning round. As captain, Chandler Egan knew he had to shake things up. He shuffled two players in the lineup, and, led by his own two-round total of 165 (lowest of the day), the WGA surged to victory in the afternoon.” Golf then took a 112-year hiatus from the Olympics, reappearing in Brazil in 2016.

Amazingly, only three gold medals from that U.S. team are known to exist. Two were discovered more than 100 years after the event. The medal won by Midlothian Country Club’s Robert Hunter, in a private collection after being purchased during an estate sale after the golfer’s death in 1971, was sold at Christie’s in London for $230,000 in 2016; the Egan gold medal was discovered in a metal box containing dozens of his other medals in 2012 before being sold to a collector for $120,000.

And then there’s the gold medal belonging to Mason Phelps, a member of Midlothian, Onwentsia Club, Chicago Golf Club, and others. It is the last known gold medal from the 1904 Olympic golf team in the hands of a player’s family, where it can be admired daily and remind his descendants of his golfing prowess.

The medal won by Mason Phelps was made of 14-carat-gold. Today’s gold medals consist primarily of silver.

“It is an absolute honor and privilege for my family to have our grandfather’s Olympic gold medal,” said Rob Douglass, the grandson of Mason Phelps.

Born in 1885, Phelps started as a caddy at Midlothian, where he won a long-drive contest. Representing Midlothian, he captured the Teen Cup at the Onwentsia Club between semesters at The Hill School in Pottstown, Pa. During his senior year at Yale University, which he attended on a full scholarship since he had no money to his name, he served as captain of the golf team. He roomed at Yale with a Chicagoan whose name still graces one of the city’s most recognizable businesses: William Blair. Phelps departed with a degree in engineering.

Mason Phelps graduated from The Hill School before attending Yale University.

Only a teenager during the Summer Games, Phelps did not take a hiatus from golf as the Olympics did. He captured the Western Amateur in 1908 and 1910, which would later be won by such legends as Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and Tiger Woods. His golfing prowess was such that, as his daughter Marian Pawlick — chairwoman of the board of The Shedd Aquarium in the 1990s — told the History Center of Lake Forest-Lake Bluff, “there were so many cups and trophies around the house that the family ended up using them as pitchers and containers.”

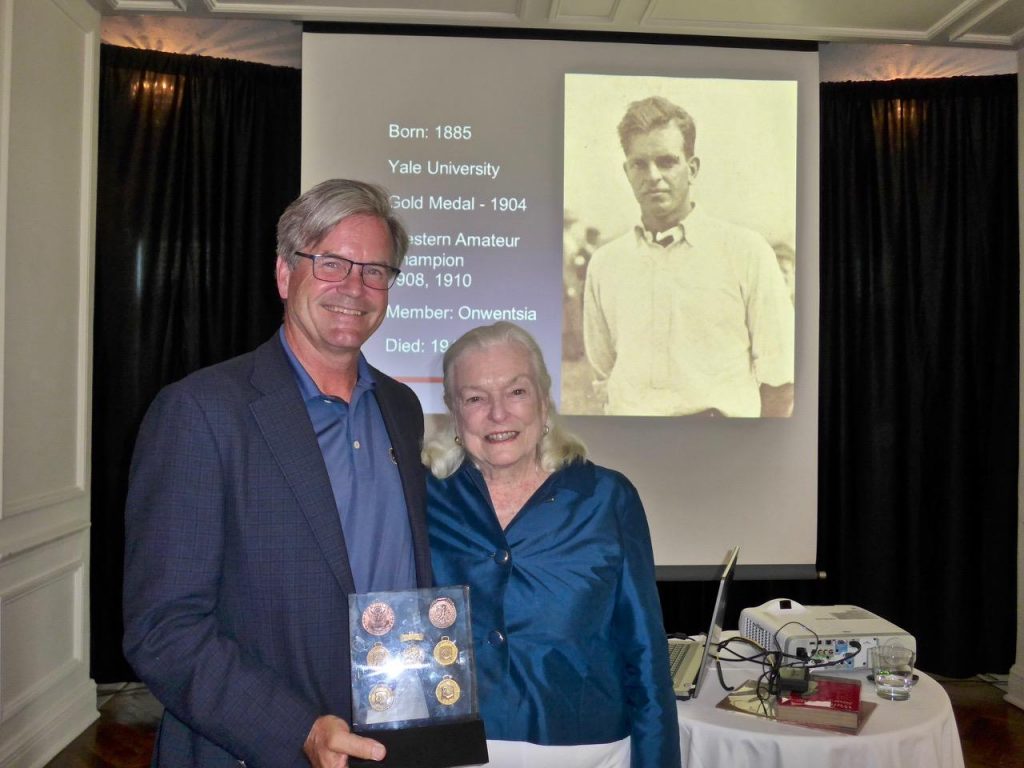

Robert Douglass and his mother, Marian Pawlick, display Mason Phelps’ Olympic medal and Western Amateur medals during an event at Exmoor Country Club.

Phelps also had a hand in creating one of the most stunning holes at Shoreacres in Lake Bluff, often considered one of the top 25 courses in the United States. When he, Robert A. Gardner and Mark Cummins met with Shoreacres first president, Stanley Field in 1919, they suggested the 12th hole could be placed in the ravine, as long as about 80 feet of property owned by McGuire & Orr was acquired. In Seth Raynor’s design, the green sits there today, a steep drop about 125 yards from the tee on the par three.

A lover of music and antiques, Phelps lived with his family in an elegant Italian Renaissance Revival house on Ahwahnee Road in Lake Forest, steps from the Onwentsia golf course. Thanks to a loan from lawyer Silas Strawn, the engineer launched the Phoell Manufacturing Co., which created fasteners for the automotive industry. The business flourished thanks to the hard work of the founder, but unfortunately, Phelps died during World War II, only 59 years of age.

Fast forward into the 21st century. After Mason Phelps Jr. passed away, a package arrived at Marian Pawlick’s house from her sister-in-law. Three medals were inside — the Olympic gold and two from Phelps’ Western Amateur wins.

“I would have loved to have played a round of golf with him,” says Robert Douglass of his grandfather.

“They were in acrylic and well-preserved,” said Douglass, Pawlick’s son, who hadn’t known the Western Amateur medals existed. “You could clearly see the dates on them.”

A bag of clubs is etched onto the front of the 14-carat-gold Olympic medal, along with thistles and the word Golf. On the back is inscribed “GLEN ECHO COUNTRY CLUB/Olympic Team/Golf Champion/Mason Phelps.” Etched on the face of a bar attached to the medal through a loop is “1904 UNIVERSAL EXPOSITION/OLYMPIC GAMES/ST. LOUIS.” The gold is little more than an inch in diameter.

When Douglass, a history buff, traveled to Merion Golf Club in Philadelphia, he checked out its archive.

“I told the Merion person there, ‘I know where one of the 1904 Olympic gold medals is,’” Douglass said. “He was shocked. It has been a mystery where they all are.”

Though Douglass never knew his grandfather and would have loved to have played a round of golf with him, knowing his impact on the sport is a balm. Said the Lake Bluff resident, “He was part of a group men and women who shaped golf throughout the Midwest as we know it today.”

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.