Town versus Country

E.M. Forster’s finest novel Howard’s End, written between 1908 and 1910, would become Merchant -Ivory’s finest film in 1992. The truest transition from word to film I have ever seen, it is set in pre-war Edwardian England when Germany still represented intellectual ideals. Director James Ivory with the bracing script of Ruth Jhabvala embraced with enthusiasm Forster’s obsession with England itself, town versus country, rural versus urban, the natural world versus the industrial —written as a rejoinder to technology loving H.G. Wells’ The Machine Stops.

Margaret sees Howard’s End for the first time.

The film magically transforms his written words into an opulent work of visual art with an exquisite production designed by Luciana Arrighi and set decoration by Ian Whittaker. Brightly colored and jewel like, mysteriously combining Impressionism’s gauzy vision with Pre-Raphaelite detail (from the Burne-Jones palette in the period interiors, the Rossetti wigs!) it is a romantic evocation of the twilight years of the old world in the sceptered isle, an England of the imagination, this imagination anyway.

The melancholy tinkling Percy Grainger score, so little heard today, with the occasional Fifth for gravitas in other scenes, reverberates during the full screen visual extravaganza of blossoms quivering fragilely in the wind, white daffs, purple foxgloves, bluebells, multicolored wildflowers in fields of dappled leaves sparkling in the sun, the landscape pure Constable. Nature is the protagonist with real estate in a supporting role.

Henry and Margaret at Howard’s End.

Oh yes, the plot. Two women of different generations, the older (ethereal Vanessa Redgrave as Ruth WIlcox,) from the Victorian world and the younger a progressive Edwardian, radiant, charismatic Emma Thompson (who won the Academy award for Best Actress for the performance) as Margaret Schlegel are united in spirit by their love of Howard’s End, Ruth’s ancestral home, a beautiful rambling country cottage of red brick festooned with lilacs and wisteria deep in the heart of England, the real England of counties not cities.. (No wonder Vita Sackville-West loved the book). It is set in the fictional village of ‘Hilton’, Berkshire but is actually Peppard Cottage in the village of Rotherfield Peppard, Oxfordshire.

Would you give my sister leave to stay the nght at Howard’s End?

Margaret and her younger sister Helen (Helena Bonham Carter in her best role), half German, haute bohemian upper class, with brother Toby an undergrad at Oxford, live in the house, crammed with pictures and books, where they were born in London— soon to be demolished for modern flats. The sisters were based on Virginia and Vanessa Stephens who Forster knew before they married Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell. (In 1968 in his King’s digs Forster told me there never was a group but Bloomsbury was just a loose association of friends.)

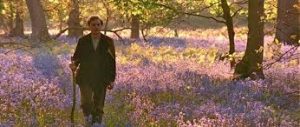

Leonard walking to Howard’s End.

Margaret, as the epigraph states, tries to “only connect”the poetry (of inner feelings) to the prose (of ordinary life) an acute challenge when she marries Ruth’s widower Henry WiIcox (Anthony Hopkins) the rich imperialist with a rubber empire in Nigeria. As she lay dying she scribbled in pencil that Margaret should inherit Howard’s End which Henry chose to ignore. Unaware of this Margaret accepts his proposal under a 40 foot ceiling in an imposing Georgian house where he has no idea whose portraits are on the walls having purchased it lock stock and barrel to fish and hunt — only to discover it was in the wrong part of Derbyshire so he was going to sell it.

Peppard Cottage, Oxfordshire.

While they do not really communicate on the deepest level she is seduced by the material grandeur and soon engrossed in building a new mansion (what happened to Hegelian ideals??). Property and the myth of progress has won her over until she is forced to choose between her husband and Helen, all passion, poetry and pregnant by a working class clerk living in a cold water flat racked by railroad noise with a blowzy wife a former prostitute. The dwellings are signifiers of social class as always in the film.

The sisters with good intentions but unaware of the real world destroy the young clerk Leonard Bast (a wonderful Jim West) who taking their advice quits the only job he will ever have. In a sublime scene on a sparkling sunlight river Helen tries to comfort him by extolling the healing power of art, “when people fail you there’s music and meaning”, to which he retorts, “That’s to make rich people feel good after their dinner.” We agree with him.

Henry’s eldest son, the unutterably snobbish Charles, thinking he is defending Helen’s honor, kills Leonard and is sent to prison, Forster’s fury at the heartless meddling upper classes bristling in the film. Margaret and Henry reconcile and Howard’s End becomes the Schlegel home after his death. Hopefully England will be in good hands, reconnecting its rural past, healing the damage modern life has caused.

Leonard and Helen in a rowboat.

The very beauty of the film is its meaning, so haunting, unlike the 2018 dark, dreary “mini” series, with its politically correct casting and anachronistic verbal cadence and observations. Spare us the scourge of updating the classics! Producer Ismail Merchant, who secured major funding from Japanese companies for this expensive effort, and James Ivory, also filmed adaptations of Henry James’s “Bostonians,” Forster’s “Room With a View” and “Remains of the Day”, and Evan Connell’s “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” all wonderful but not magical Howard’s End.