By Cheryl Anderson

“Fashion changes, but style endures.”

— Coco Chanel

Coco Chanel was introduced to Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovitch while on a trip to Biarritz in the summer of 1920 with her friend, from her life at Royallieu, Marthe Davelli, a famous soprano. Although, she told Paul Morand she had previously met him in 1914, but hadn’t seen him since then. Tsarist Russia had collapsed. Dimitri was an émigré from Russia — many Russian émigrés found refuge in France escaping the massacre.

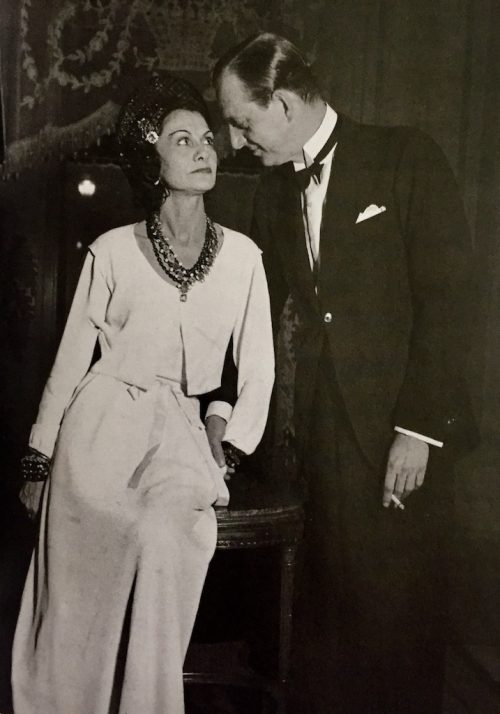

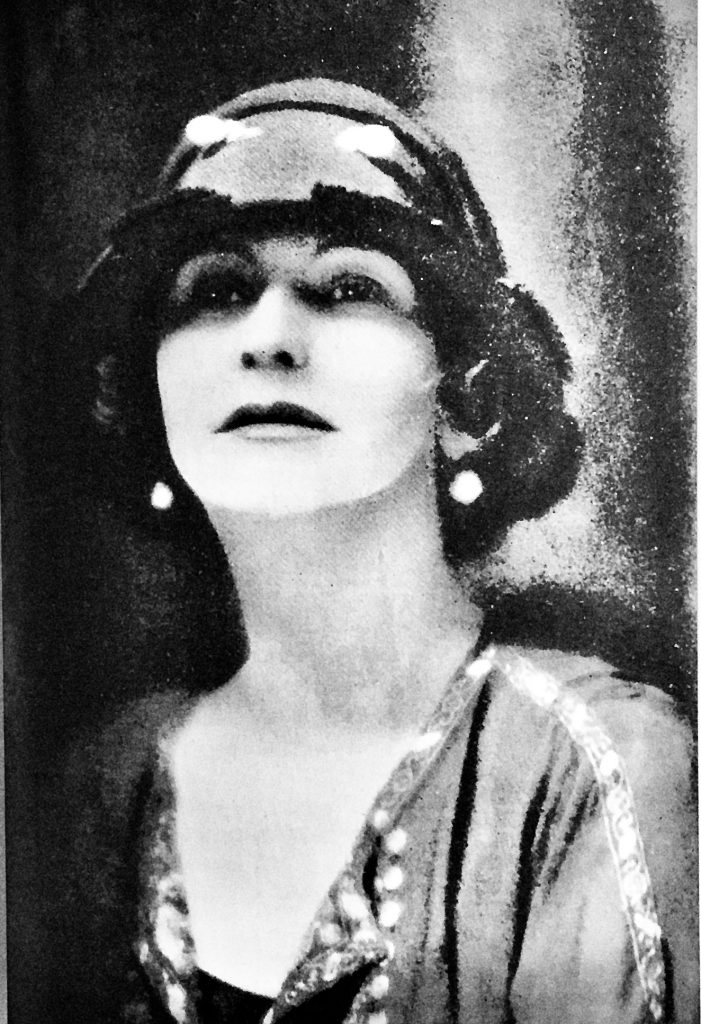

Chanel and Grand Duke Dimitri (1920).

Chanel gazing into the eyes of Grand Duke Dimitri. Shown wearing her evening pajamas — with bolero jacket and trousers.

At the time of their meeting, Dimitri was Marthe’s lover, but soon Chanel lured him away with Marthe’s blessings, reportedly saying he had become too expensive for her. Chanel was involved with Igor Stravinsky at the time, but that didn’t stop her from pursuing Dimitri. Her liaison with Stravinsky would end, but they would remain friends. Chanel and the handsome Dimitri, eleven years her junior, with his Slavic charm and the mystery that surrounded him, were inseparable for only one year, but they too would remain loyal friends thereafter. Mlle Chanel liked his style, that of a true aristocrat, raised by English nurses in a vast St. Petersburg palace.

Previous to fleeing Russia, Dimitri had been one of that country’s richest men, member of the elite Russian Guards Regiment, grandson to Tsar Alexander II, and first cousin to Tsar Nicholas II, but was now nearly penniless. Although, he did depart Russia with a stash of precious jewels. He showered Chanel with ropes of fabulous pearls, chains of heavy gold, crosses covered with rubies, emeralds and semi-precious stones. The Byzantine style of some of the pieces Dimitri had given her would make its way into her line of jewelry that was to come years later. Quoiting Chanel, “Why does all I do become Byzantine?”

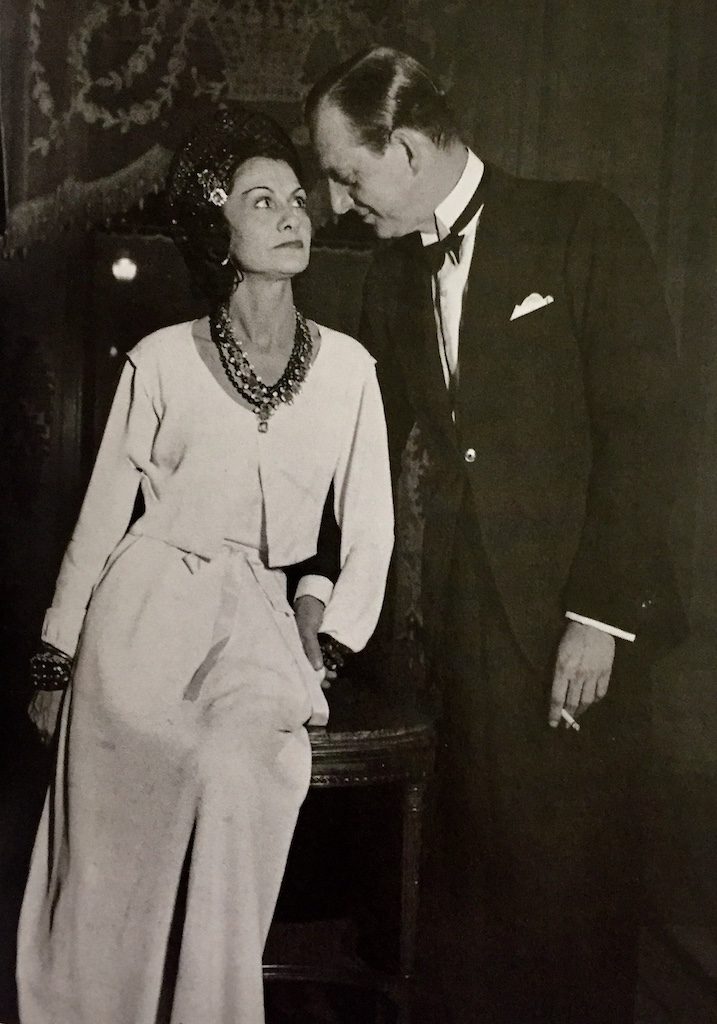

Chanel wearing pearls given to her by Grand Duke Dimitri.

She, in turn, gave him a handsome wardrobe and a delightful summer in her beautiful leased villa at the beach near Bordeaux. In the early 1920s, Dimitri and his valet, Piotr, were also guests at Chanel’s villa, Bel Respiro, in Garches (in the western suburbs of Paris). The playwright, Henri Bernstein, her neighbor in Garches, was an admirer. Chanel was photographed taking his daughter, equally decked out, for a stroll in the streets of Garches. In the photo, she is wearing a sports cape. The capes that the American volunteers of the YMCA wore prompted Chanel to design one — it became part of her 1920 collection.

9. 2208 Chanel in her sports cape with Henri Bernstein’s little daughter in Garches (1920-23). Chanel was thought of as the creator of sports fashion.

The volunteer’s cape of the American YMCA was Chanel’s inspiration for her sports cape.

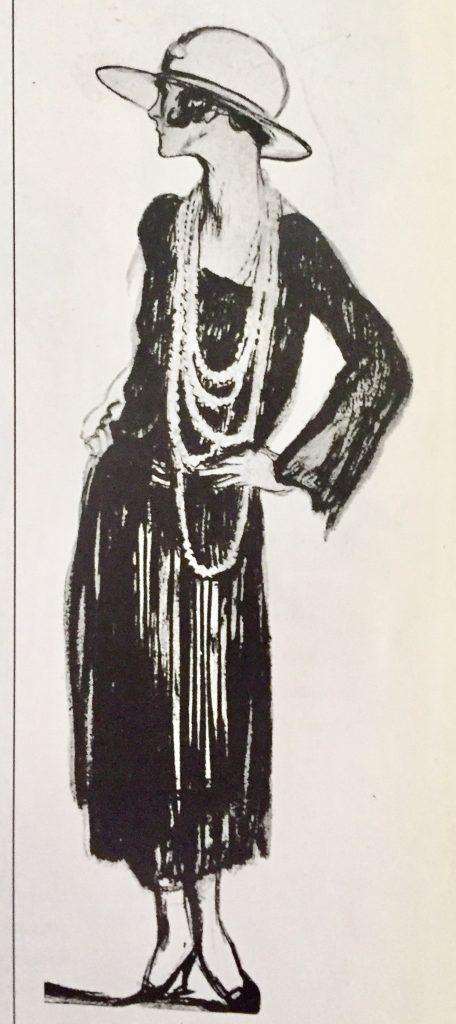

Author, Janet Wallach, in her book, Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, states: “Dimitri’s Russian influence would soon inform her work…Adorned with Dimitri’s gifts, she was shown in Harper’s Bazaar wearing a short dark tunic, pleated skirt, and a mass of ‘dazzling’ pearls. The editors credited her with ‘making simplicity, costly simplicity, the keynote fashion of the day.’ In her showroom, svelte Slavic girls with high cheekbones and good connections started modeling, kissing Dimitri’s hand and calling him ‘Majesty.’ ”

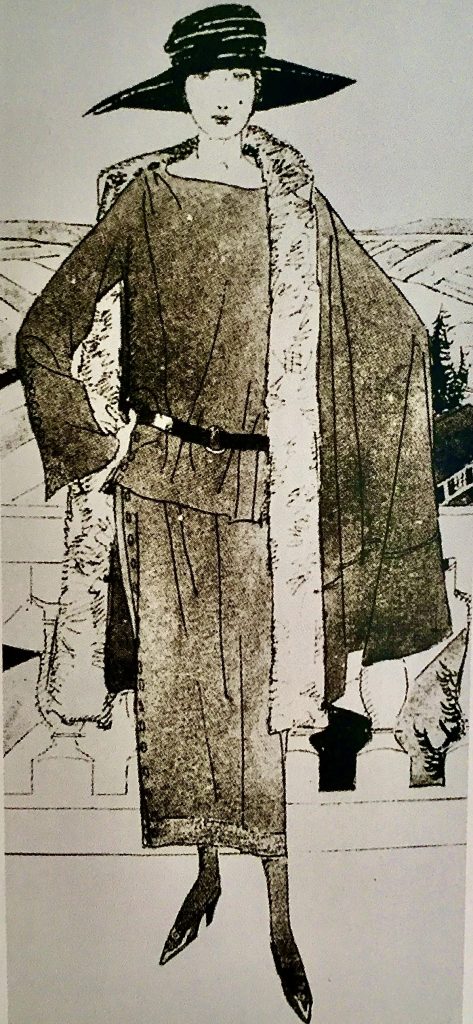

In Harper’s Bazaar, Chanel was shown in a short dark tunic and pleated skirt with ropes of pearls. A sketch of what that looked like.

Dimitri’s sister, Grand Duchess Marie, also in exile, lived in Paris and often visited the Chanel studio on rue Cambon. Marie would become an influencer in Chanel’s Russian designs. Part of the Duchess’ proper education was to learn how to sew and she was skilled in the art of embroidery. Much the way Chanel felt when she began, the Duchess wanted to earn her own living and pay her own way. Marie had been forced to sell her jewels to support her family and brother — lamenting that the days of living amidst royalty and the European courts were over. She wrote about her family this way: “We had been torn out of our brilliant setting, we had been driven off the stage still dressed in our fantastic costumes. We had to take them off now, make ourselves others, more everyday clothes.”

The Duchess decided that the new social and economic situation in life was not going to force her to just give up. Her close observation of Mlle Chanel’s work ethic, how she ran her business, and her dogged determination were attributes that Marie could understand. Chanel’s business sense was to cater to the public in a broader sense-making the chic Chanel standard to appeal to every woman’s taste. Considering her background, Marie was never a big fan of public taste, never the less, she saw the sense in catering to it.

She offered to charge less than what Chanel’s French seamstresses were charging for embroidery and beadwork — Chanel hired her. So, with a few skilled friends, she opened a workshop. Janet Wallach states: “They began by embroidering blouses and traditional Russian tunics, and soon expanded their efforts to jackets and coats worked with passementerie, and to evening chemises studded with bugle beads and pearls. As the embroidered look became popular, they expanded their vocabulary to include patterns copied from Chinese vases, Coptic weaves, Oriental rugs, Indian jewelry, and Persian miniatures.”

Chanel in a Russian inspired blouse — her own design (1923).

A sketch appearing in Vogue (1922). Tunic, kasha-colored khaki, skirt buttoned on the side with a leather belt.

Marie was always aware she was under the watchful eye of Coco. Wallach describes Chanel’s command of her workroom like this: “No matter what aristocratic titles her employees held, it was Chanel who reigned supreme. Her wish was obeyed, her orders prevailed, her word overruled all else… From the start, Chanel was completely in charge of her collection.”

Jersey was still the staple of the House of Chanel, but the Russian look became so popular that Marie, along with designers and technicians, grew her business to fifty or so employees producing beadwork and embroidery — naming her company Kitmir. Kitmir was the name of the Pekinese dog belonging to the former ambassador to Washington. Her embroidered garments were the centerpiece of Chanel’s spring collection in February 1922 — the styles became favorites of many of Chanel’s clients.

Chanel needed large quantities of embroidered garments and machine embroidering made sense. It wasn’t necessary to have embroidery done by hand — the visual effect was what she sought. This same philosophy of the visual effect would occur later on when she launched her costume jewelry. According to Justine Picardie, in her book, Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, after buying a sewing machine, Marie spent a month in a factory in a very poor part of Paris learning how to use it — then she bought an embroidery machine, putting it in the front room of her apartment, and learned how to use it.

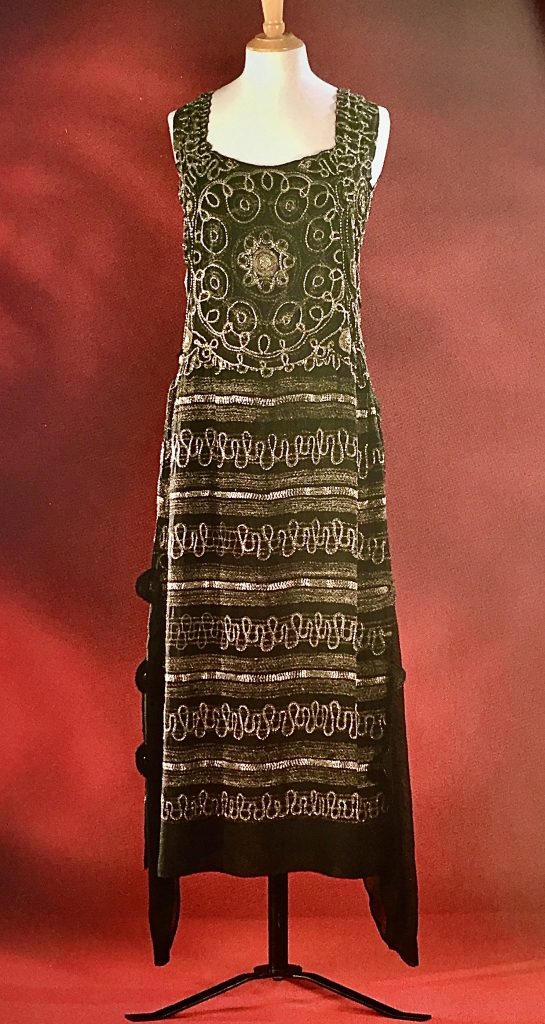

Silk georgette dress decorated with clear bugle beads all over, black and metallic gold embroidery (1922).

In the Duchess’ memoir, she says: “It took me about month to learn the intricacies of an embroidery machine…seating myself on the sofa, I looked at it from a distance. It stood there on the carpet between two armchairs and a table with knick-knacks and photographs — hard, sturdy, and aloof, with the light gleaming coldly on the polish of its steel parts…Just once or twice in my life, my past with all its antecedents has appeared to me… seen from a new angle, like the impression one gets in looking at a familiar landscape from an airplane. This was such a moment, and it made me feel small and helpless.”

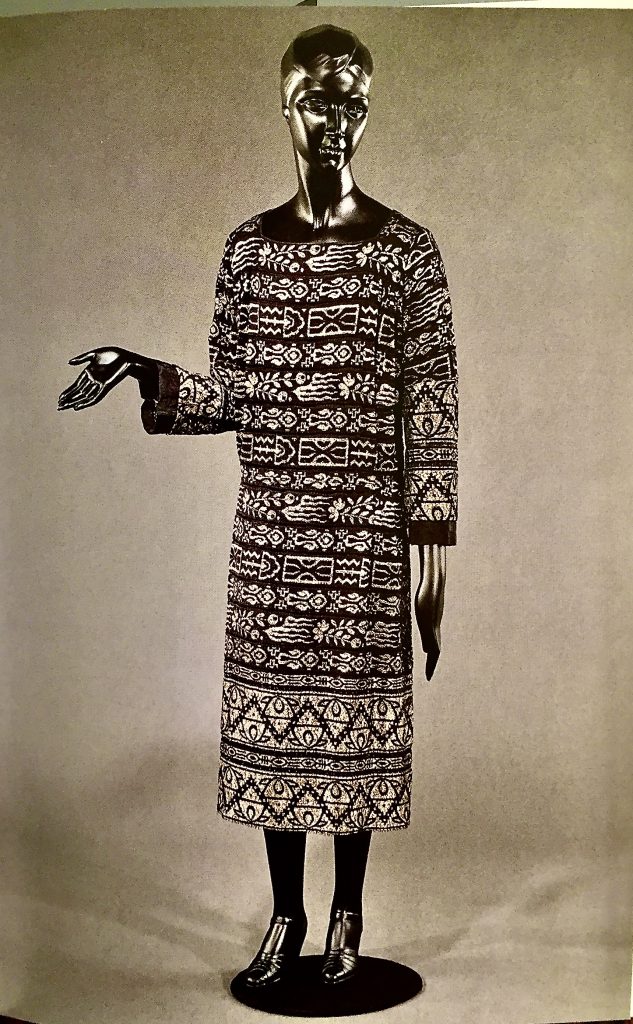

The Chanel peasant dress was born during this period — made chic with ropes of pearls. Russian influence can be seen in her interpretation of the square neckline of the roubachka (an embroidered blouse or tunic commonly worn by Russian peasants), the pelisse (a military-style coat with frogs) and the sailor’s jacket whose line mimicked the Russian military uniform. Edmonde Charles-Roux states: “Chanel adopted the Russian peasant blouse — the long, belted rubachka traditionally worn by muzhiks (peasants) — and made it the uniform of chic Parisiennes. Clearly, Russia had entered the designer’s life.”

Peasant style dress — Black wool shift with gold embroidery of Russian folk art (1924).

It’s not unexpected that the use of fur would find its way into Chanel’s Russian Period — lavish fur-trimmed outfits and fur-lined coats. Chanel had used fur trim in the past, leopard, monkey, and fox, but never as much as between 1923-1924, adding Siberian skins, sable, ermine, and mink. Combining embroidery with fur was new, chic, and caused a stir in the fashion world. Baron de Meyer, a well-known columnist and photographer, wrote in Vogue as being wowed by Chanel’s embroidered white coat with Russian sable trim.

Sketches and text of some of Chanel’s fashions from the Russian Period.

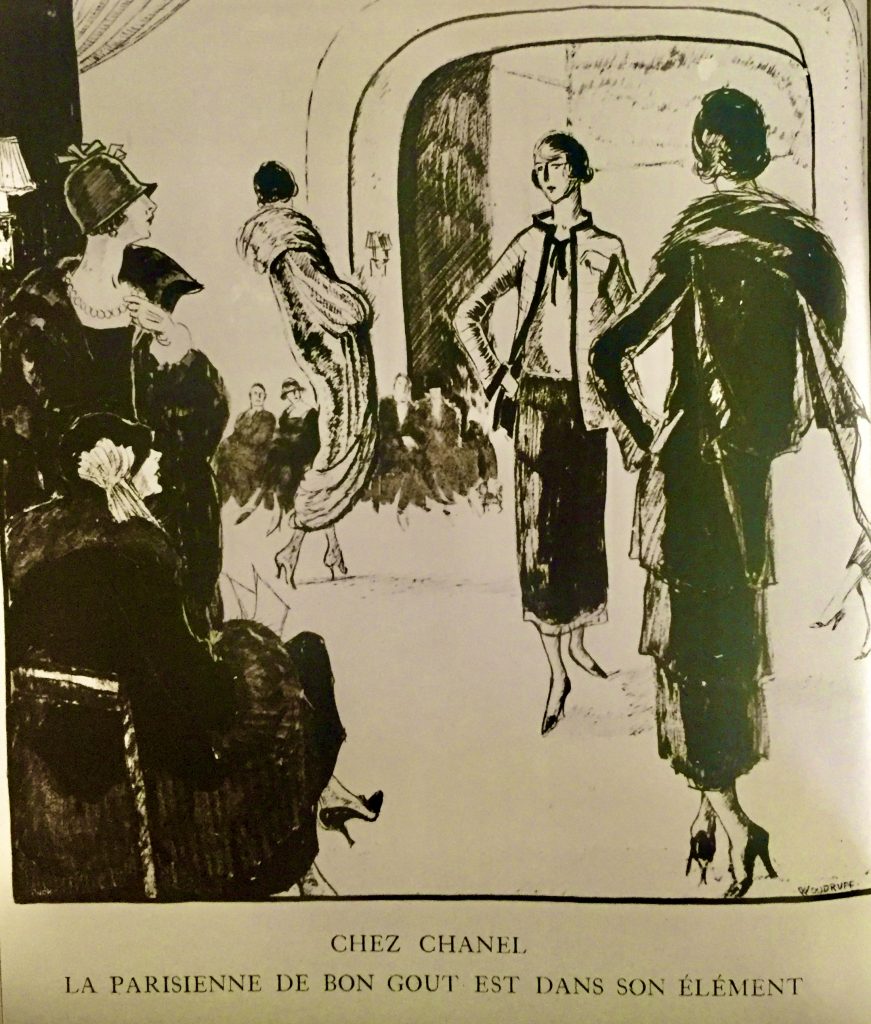

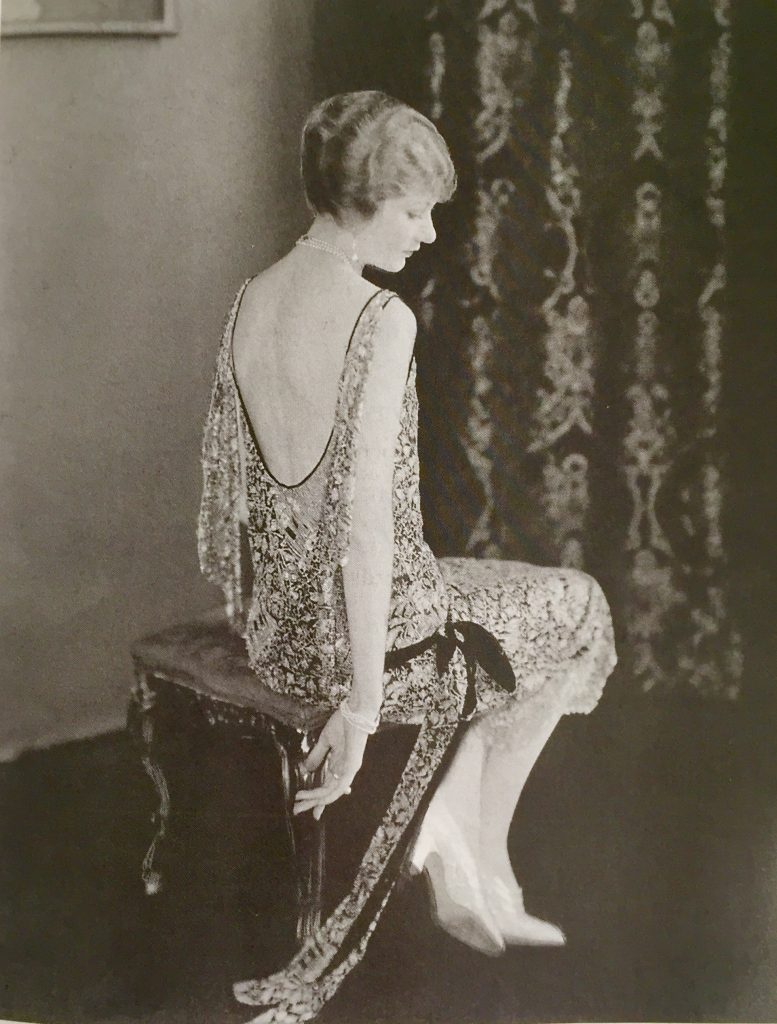

Edmonde Charles-Roux, when commenting on the Woodruff drawing in Vogue (1923), wrote: “Never would so many fur coats and fur linings be seen at Chanel’s as in these years (1923-1924).” Also of note, from this period, are the graceful embroidered hand-beaded waterfall gowns that shimmered and swayed in the rarefied atmosphere of the early 1920’s world of Coco Chanel.

A Woodruff drawing appearing in Vogue, 1923.

A demure young lady wearing a beautiful waterfall gown of crystals and jet.

Chanel’s Russian Period was also the period when one of the most popular and sought after fragrances in the world, Parfum Chanel Nº5, was launched (1921). Its huge sales made Chanel economically independent for the rest of her life. I will share with you the myths and legends surrounding Chanel Nº5 in the next installment of Coco Chanel.

À bientôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by It Books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

Pictures from:

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books