BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Editors Note: How have Chicago artists translated the pandemic and this time of social unrest through their work? We share their creative process and powerful results in Part 2 of this series.

With their latest creations, we learn more about how gifted artists Melanie Parke, SHENEQUA, and Janet Trierweiler are impacted by the isolation and uncertainty of COVID-19 and the current context of the Black Lives Matter movement. They inspire not only through their art but with their insights.

Melanie Parke.

A graduate of the School of the Art Institute, Melanie Parke grew up on a small horse farm in Indiana. She and her husband, Richard Kooyman, organize an artist-run project space, The Provincial, in the little village of Chief, Michigan, where they now reside. Her work is currently on view as part of a spectacular solo show at Kenise Barnes Fine Art in Larchmont, New York, and closer to home at Anne Loucks Gallery in Glencoe.

What are you working on right now and how has it been affected by what’s going on around us?

I feel change afoot within my practice. I recently began a new series of gouache on paper, titled DOMUS. Domus means “house” in Italian, in particular the Imperial-style homes of the second century BC, like the ruins seen in Pompeii and Herculaneum with courtyard gardens, fountains, and frescoed interiors. These ancient painted walls narrate mythic stories populated by bodies, birds, and flora and fauna.

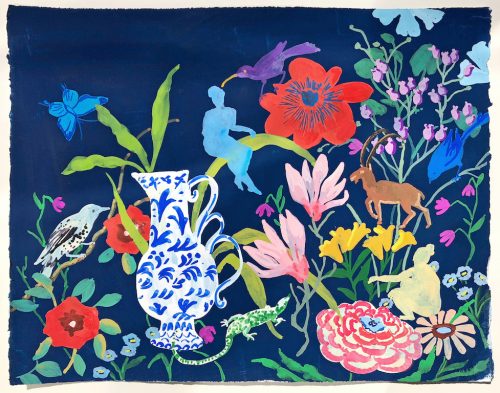

Night Pogonia, 2020, 16×20, gouache.

The idea of DOMUS resonated as a historical springboard to think about how much time we are spending in our homes now during COVID-19 and how much time women have been confined to the home for centuries. Ideally, the home is a place of protection and comfort, but for women and children, it is often a place of great peril as well. This concern drives the work.

I find the figure is a powerful presence to illustrate female imagination, desire, and longing. We have yearned for safe places for so long. What do they feel like, what do they look like? DOMUS is also a way to re-think the loaded uses and implications of what is domestic. For instance, domestic abuse is such an unsettling term. When to domesticate means to cultivate, and to cultivate is to grow, to love, to support and nurture, abuse is particularly antithetical within the protective spirit of home. And yet, it’s been unsafe for women and children of all ethnicities for centuries. I worry that when we imply domestic as in domestic abuse, it is brushed off as unknown and invisible: invisible abuses, coercions, rape, and murder.

Golden Urn, 2020, 16×20, gouache.

With all eyes on police brutality against black lives, I really appreciate how #SayHerName calls attention to the names and stories of crimes against black women as well, often committed in the home. 26-year-old Breonna Taylor was murdered in her own home, so was 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, and so was 92-year-old Kathryn Johnson.

I think we are in an amplified moment when not only are the streets unsafe, the home is not safe. The police, the very framework claiming to keep us safe, are causing greatest harm, and nothing feels safe right now. And it needs re-imagining and it needs visibility.

Is there a personal resonation for you within these issues?

I am a feminist. I am a survivor. I was repeatedly beaten and sexually assaulted by a male babysitter as a child. He was never prosecuted but would go on to abuse many others. This experience informs my life and work with a very clear and conscious purpose to use my voice.

On the upside, I am fortunate to come from a multi-generational family of anti-racist activism. My great-great grandfather, William Camp Gildersleeve, was tarred and feathered for being an abolitionist leader, part of the Underground Railroad. A white mob yanked him from his home, tarred him, and paraded him and a wooden beam through the town of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for housing and promoting anti-slavery speakers. Gildersleeve survived, but none of the perpetrators were arrested. My grandmother was an oral family historian and told me these stories over and over when I was growing up, and they seared in my consciousness.

My grandfather on my mother’s side was a young journalist covering the horrific public 1930 lynching of three teens in Marion, Indiana. He had tried holding back a white mob on the jailhouse steps, but with sledge hammers, they tore into the jail, brutally beating the young men and publicly hanging them from a tree in the courthouse lawn before they were given a fair trial. Miraculously one of the teens, James Cameron, survived and would go on to establish America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee.

My late father was an abolitionist writer and historian in Indianapolis. Wanting to expose Indiana’s dark racist history, he provided research to the Indiana African American Heritage Trail, the Indiana Historical Society, and the Society of Indiana Pioneers.

It helps to have been born into these generational dialogues but is it enough? Is what I paint making a difference? These are difficult internal dialogues I confront all the time, and I think it’s important to remain vulnerable, to be in a constant state of learning in the process of thinking through these ongoing tragedies of abuse and unrest.

Do you think the way you create is changed going forward based on everything that has happened this year?

I feel life is that much more precious and fragile. I feel a heightened awareness of the brevity of it all: health, relationships, small pleasures. And I feel driven to be engaged in whatever way I can.

As an artist, what unique perspective can you share about responding to everything right now?

With the pandemic, we are faced with vast layers of immeasurable, epic, global collapse. And it just keeps coming: irreplaceable loss of life, home, livelihood, and futures. And I think it takes time to survive and find your way. We need to be kind to each other.

But if possible, I think uncertainty can be a fertile place to be. It takes some practice to be in that state of mind, but when one sits with it or bumbles around awhile, expectations are shifted allowing new prospects to show themselves. Artists tend to utilize isolation as a playground of thought and experimentation.

It is often said that the most difficult thing an artist faces is the blank canvas. With the pandemic leaving in its wake so many empty spaces, physically and psychologically, I think artists are especially adept in making gestures of possibility and propositions, imagining what something else might look like. I think it will take this kind of brave imagination and creativity going forward to rebuild a healthier world for everyone.

Butterfly Leopard, 2020, 16×20, gouache.

Night Vision, 2020, 16×20, gouache.

Has your creative process helped you get through the pandemic?

Absolutely. As a survivor, I developed tools to navigate trauma, searching for life on the other side—the most valuable tool being the imagination.

Resisting depression is akin to resisting oppression. It is a process of rerouting our thinking. Forging new pathways mentally, physically, socially, and politically. For me, creativity combines critical thinking with determination to investigate how it might be possible to transform harm into vitality.

Shenequa Brooks.

Shenequa Brooks, who as an artist refers to herself as SHENEQUA, describes herself as “a black Caribbean woman and Artprenuer.” She is part of a cadre of teaching artists for the non-profit Changing Worlds, working with students in Chicago Public Schools develop self-discovery through the arts.

Tell us about your art, its evolution, and influences.

My familial background, conversations with others, and Ghanaian experience influence my art practice. My art is born from the traditional craft of weaving and transitions into a wall hanging, sculpture, performance, fabric, or ‘garment’ pieces. I got into weaving when I was in undergrad at Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI) in Kansas City, Missouri, where I studied fibers and textiles.

My art practice has shifted in the process of making. I’m making around the idea of celebrating the men and women in my life that have inspired me. There is a shift on the horizon in my art practice that I don’t know of as yet, but I know it’s going to be a great one.

What do your students learn from you as an artist about weaving? How do they express their feelings through their own weavings?

My students learn how to express their feelings and experiences through weaving. They come up with their own language or code. They speak through color and pattern to tell their own stories.

Have you found that you are responding to these times consciously or subconsciously through your work?

I’m responding to these times both consciously and subconsciously. I live by myself in Chicago away from family, so when I’m working on a piece about my family, it makes me feel like they are right here with me. When I center the work on celebrating life, love, and prosperity it makes me feel optimistic about life despite the craziness, injustice, and sickness of it all.

Grandma Violet.

How has your art evolved during this period and do you think the way you create will change going forward?

It has evolved in the process in which I’m producing my work. So instead of making everything by hand, I am outsourcing and getting it digitally made, and approaching weaving in a different way by taking it apart, collaging, sewing, and beading. I think that the pandemic has influenced the way I think about making, and how I move as Black Caribbean women in America.

Black on Black, with detail.

Black Hair with Gold Trimming, overview and detail.

How are you responding to the uncertainty and isolation right now? What do you miss most?

I’ve been an Artprenuer for a year now and uncertainty of what’s next kind comes with it. Nothing is really certain unless you manifest what you want in life with actionable goals to follow but even so, things don’t always go as planned. Being isolated from those I love and care about has been difficult during this pandemic, but I do live and work alone. I just miss being social, hugging, and kissing.

How has your work and process helped you through this time?

I definitely have found comfort in making during this time. Also, I’ve found comfort in slowing down even when I make—not to add pressure on me and take it a day at a time.

Janet Trierweiler.

Janet Trierweiler describes her pre-COVID-19 work as “gestural abstractions,” saying, “If there is an image for what the process of change looks like, that is how I like my paintings to look. They’re fluid and energetic like weather.”

Tell us about your current work.

The changes that occurred from being sheltered in place for so long have to do with an even greater appreciation for Lake Michigan. Walks and bike rides to the lake have been not only for exercise but also to witness a new scene every day: the water was ferocious or still or just welcoming and gorgeous.

At the lake during the quarantine.

I started ordering large quantities of pet food online and the packaging caught my eye. The boxes my cat’s food came in had a bright orange band around them. I couldn’t wait to paint on them. I chose blue to contrast with the orange, and that led me to think about the lake. These small abstract box paintings inspired a series of large paintings on canvas, all based on memories of my visits to the lake. I use fluid oil paint for all the work.

Abstract Lake Study, 7x11x2.5 in, oil on cardboard.

Abstract Lake Study II, 7x11x2.5 in, oil on cardboard.

How has your process helped you during this time? What about it has surprised you?

Art can be so healing. It’s the unexpected that drives my painting process and keeps me working with enthusiasm. It teaches me to pay attention and appreciate what’s around me. I believe the subconscious will bring up things that need our attention. If we’re listening, we can take this information and process it consciously. This is why art requires inner and outer quiet space. Painting, like yoga, is a practice. It’s hard to show up, especially in these times, but once you start, you get into the flow of energy, which keeps you going.

In terms of surprise, I’ve been compelled to write stories from a flood of memories I’ve had since witnessing the devastating video of George Floyd’s senseless and cruel murder. These memories and stories involve the black people in my life, including friends, teachers, and helpful strangers. The writing makes me think in new ways and question my own understanding of their experience. The Black Lives Matter movement has helped me to realize the immensity of the brutality in our country toward black and brown men and women. I’m not alone and for that I’m grateful and hopeful that we can find new and creative solutions to alleviate all the fear and hatred in this country. These times are a call for creative, compassionate, and thoughtful response.

How has your art evolved during this period and do you think it will continue to impact the way you create?

Being at home and arranging life around a pandemic has made me much more aware of time and organization. I was an everyday shopper: we’d decide what was for dinner a few hours before and go to the store to get it. We’re friends with all the checkers at the grocery store because we were there every day. Now we shop for two weeks at a time.

So many things in our lives have become less casual. This new formality has shown up in my painting. I’m far more interested in geometry, borders, and edges in the work than I was before the virus. Previously my paintings had a suggested, underlying geometry, which has become more present and plays more on the surface in contrast with the expressive, gestural forms. I’m enjoying how this new formal quality in the work creates a balance with the more fluid areas.

Intuition, 32×43 in, oil on canvas.

Phrases, 32×43 in, oil on canvas.

As an artist, what are your thoughts on the isolation and uncertainty of these times and how to cope?

Isolation is the hard one. We can get caught up thinking about it too much and what we’re missing. Turning our attention toward doing something, even a small gesture, for someone else may seem counterintuitive when we feel needy ourselves, but it really helps. It requires a bit of creative thinking and that in itself can lead to more positive feelings.

In terms of uncertainty I’ve let go of things I have no control of for now and appreciate the little things. My daughter graduated from high school this year. She had a virtual ceremony. I couldn’t have enjoyed it if I compared it to the ceremony my older daughter had. I felt I needed to bring my enthusiasm to watching it with appreciation for all the effort and beauty and love that went into creating it.

***

For more information about Melanie Parke, visit melanieparke.com or @missmelanieparke on Instagram. Shenequa Brooks can be found at shenequaabrooks.com or on Instagram @shenquabrooks. View Janet Trierweiler’s works by visiting janettrierweiler.com or @jtrierweilerar on Instagram.