By Melissa Ehret

From the mid-19th century and especially after the 1871 fire that destroyed much of the city, Chicago began to experience astounding growth. Opportunities for advancement were rampant. Farmers’ sons could become millionaires presiding over a department store empire. A man with a vision to design railroad sleeping cars not only amassed a fortune, but, for better or for worse, established an entire town bearing his name. And amazingly, for some 25 years or so, a great majority of Chicago’s wealthiest citizens decided to assemble their palatial new homes on a six-block stretch of one street: Prairie Avenue.

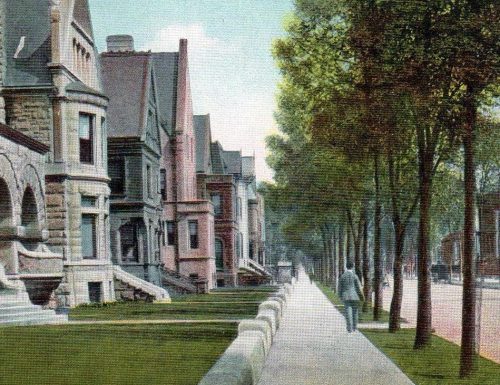

A postcard of Prairie Avenue, circa early 1900s.

Romanesque fortresses and French chateaux began rising on what would soon be dubbed “The sunny street that held the sifted few.” Some of the world’s premier residential architects such as H.H. Richardson and Richard Morris Hunt arrived from the East to witness their extravagant designs take life. Trips to Europe enabled newly rich homeowners to acquire prized antiques and to buy paintings from then-unconventional artists such as Degas and Monet. The Herter brothers, considered to be the finest creators of furniture at the time, populated many interiors with their exquisite cabinetry. Rare, delicate orchids thrived while sleet pounded the glass walls of elaborate conservatories attached to the mansions. All that was left to do was to show the trophy houses to their best advantage. Given all that had been spent on these showcase homes, it was incumbent that entertaining be executed comme il faut.

Some of Chicago’s social elite migrated from the East and South, where they had been raised in affluence. Bertha Palmer, daughter of a wealthy Kentucky family, had been schooled to excel in fine arts and deportment. The brilliant, confident Mrs. Palmer had all the attributes of a social leader and philanthropist. Other women, married to self-made men, were bewildered as to how to navigate the shallow, subtly shifting channels of conduct they had perhaps observed only from afar. How did one assimilate into a new, yet intimidating culture? How, exactly, did one become social?

Matching the extraordinary passion that powered Chicago’s founding businessmen, their spouses were driven to show that they could play the game as well. Whether that drive was borne from the need to provide visiting dignitaries with suitably impressive entertainment, or compulsion to keep up with the Fields and Pullmans, the ladies of Prairie Avenue were relentless in establishing a formidable social order.

According to the 1953 book, Fabulous Chicago, “The chief characteristic of Chicago society was its newness.” The author, Emmett Dedmon, went on to describe how Prairie Avenue was Chicago’s virtual birthplace of luncheons for ladies, perhaps the precursors of the “ladies who lunch.” Calling hours were established as was the leaving of calling cards on silver salvers. Dinner parties started consisting of food that were considerably more elaborate than meat and potatoes.

One of the most influential figures in elevating the domestic culture of the newly wealthy was Herbert M. Kinsley. An East Coast hotelier and restaurateur, Kinsley experienced many ups and downs in his career prior to settling in Chicago. After opening and closing several restaurants, and experimenting with the first Pullman dining cars, Kinsley finally found success in the 1880s with his palatial establishment on Adams Street. Kinsley’s was not only the dining place of choice for Chicago’s wealthy, but it provided unparalleled catering services. With his Eastern connections and knowledge of fine food, Herbert Kinsley became the premier consultant for at-home entertaining on Prairie Avenue.

Kinsley eventually became an arbiter of good taste (no pun intended) for Chicago society. He published books on etiquette, how to conduct proper afternoon receptions, and instructions regarding appropriate attire and jewelry by occasion. He even maintained a glossary of French phrases and witticisms that one could artfully slip into conversations. Existing artifacts from Kinsley’s restaurant, such as the 1885 Gorham soup tureen below, shows an insistence on elegance and quality.

Prairie Avenue also became home to an increasing array of sophisticated help: Matrons began to recruit the most sought-after butlers, footmen, cooks and governesses they could find. According to the delightful Prairie Avenue Cookbook, “Few households were as large as the Marshall Field’s, and Mrs. Field was reputed to have on staff ‘a representative from nearly every civilized nation of the globe.'” Families would “borrow” the best of their neighbors’ staff for major parties, no doubt astonishing guests as to the quantity and sophistication of help amassed by these Midwestern hostesses.

The presence and gentle influence of English butlers and French cooks could help confer instant patina upon families whose previous help consisted of a penniless chore girl or two. A butler might be counted upon to pack the Sevres china for a picnic in Jackson Park, as illustrated in Arthur Meeker’s novel, Prairie Avenue. A lady’s maid may have suggested to the lady of the house that a diamond parure was not really necessary for an informal outdoor event.

To ensure they were as culturally informed and conversationally adept as any New York hostess, the ladies of Chicago began to organize clubs, including the Fortnightly and the Twentieth Century Club. According to Fabulous Chicago, the original purpose of the Fortnightly was the dissemination of both “social and intellectual culture.” The same book identifies Mrs. George Roswell Grant as founder of the Twentieth Century Club, who noted that, “when a distinguished foreigner … comes to Chicago, they want to meet the representative society people. They don’t care about being bored with a lot of men who have a local reputation as men of genius… they want to meet people whose names are known as men and women of fashion.”

Mrs. Frances Glessner was a cultural institution in and of herself. The Prairie Avenue resident was the founder of the Monday Morning Reading Class, a group that fostered friendship among Chicago’s intellectually active women and faculty wives from the new University of Chicago. Mrs. Glessner was also a member of the Fortnightly, the Colonial Dames, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

The children of Prairie Avenue were seen as extensions of their parents’ accomplishments. For the privileged boys and girls, there were governesses fluent in multiple languages, private tutors before entry into Eastern prep schools, and equestrian instructors. Then there were the obligatory lessons at Bournique’s. It became far more than a dance academy, which was its original purpose when established in 1867. Bournique’s was a place where, per an 1883 Chicago Tribune story, “particular attention is given to gracefulness of motion, courtliness of deportment and modest self-confidence, all of which are so essential and characteristic of well-bred people.” The Bournique’s became sufficiently successful to have opened several locations. The most opulent was in a newly constructed building near Prairie Avenue, designed by the architectural firm of Prairie Avenue resident Daniel Burnham. It boasted a huge ballroom with a dance floor composed of more than 173,000 pieces of hardwood.

The intrepid people of Prairie Avenue were visionary, even in their social legacy.