BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

One of the country’s top holiday home tours according to USA Today and 10Best awaits you at the mansion anchoring the avenue that bespeaks Chicago glamor in the Gilded Age.

Accompany Glessner House’s Executive Director and Curator William Tyre and Classic Chicago to learn about visions of sugar plums in the 1890’s when Chicago and its Columbian Exhibition captured the world’s imagination through our tour below.

And plan to visit in person on Saturday, December 21 for a candlelight tour of the H. H. Richardson landmark home built in 1887 for John and Frances Glessner, which welcomes visitors to perhaps Chicago’s most fashionable block. Tours start every 15 minutes, beginning at 4:30pm with the last tour at 6:30 pm. Refreshments, including Mrs. Glessner’s hot cider, follow in the coach house. Advance tickets are required.

Glessner front door.

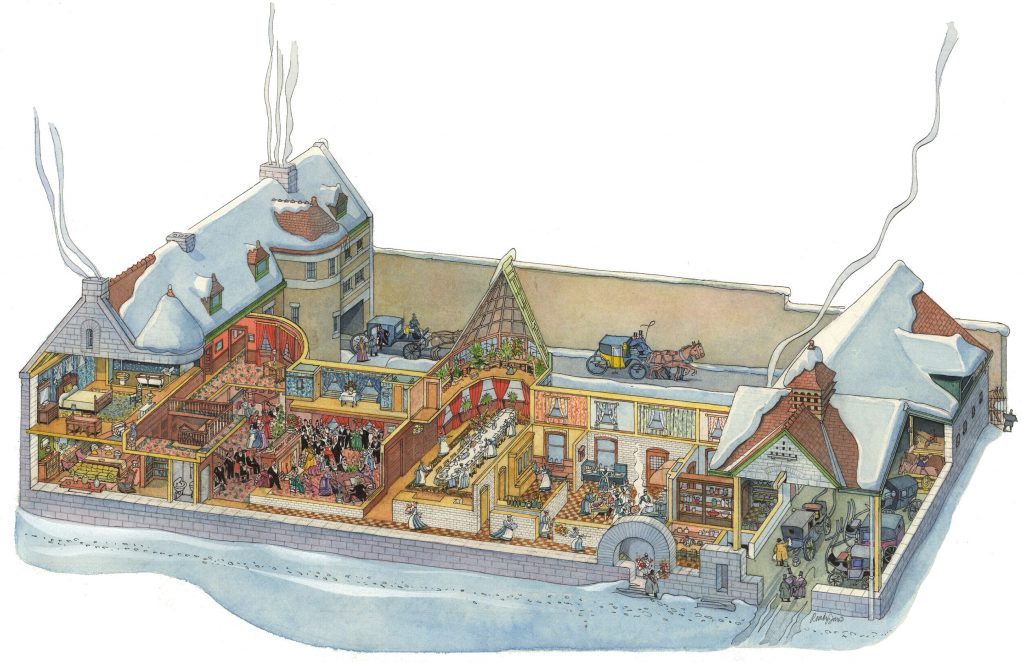

“Christmas at Glessner House” by Randy Jones represents an 1890’s Glessner House Christmas party and depicts the hustle and bustle throughout the house when the Glessners entertained.

Prairie Avenue’s heyday, when social leaders such as the Glessners anticipated the upcoming World’s Fair of 1893 and entertained Chicago’s new industrialists, most of whom were their Prairie Avenue neighbors, is captured each Christmas for visitors. John Glessner, who with the merger of his own company helped create International Harvester, and with his wife Frances, a jewelry designer and canny hostess, made a significant impact on many of Chicago’s cultural institutions. They lived there for 50 years and experienced the evolution of holiday traditions.

Main Hall Christmas Tree.

German settlers first introduced Christmas trees to America in the 1750s. They did not, however, become widely used until the mid-19th century when Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, introduced the customs of his native Germany to Great Britain. As was true in most American homes in the late 19th century, the Glessners’ first Christmas trees were small two or three-foot high balsams or Douglas firs set on tabletops.

Schoolroom Christmas tree.

In an 1888 journal entry, Frances Glessner described some of the Christmas preparations for the family’s second holiday at 1800 S. Prairie Avenue: “The children are today trimming a Christmas tree in the school room. We all hung up our stockings and trimmed our pretty little tree just three feet high…”

George Glessner photographed the schoolroom tree that year, and the photograph is on display today.

By the end of the 19th century, taller trees were often chosen for decorating American homes. The Glessners had their Christmas tree cut each fall at The Rocks, their summer estate in New Hampshire, and had it shipped it to Chicago by rail. They started this custom by at least 1900, when a tall tree in the hall is mentioned in Frances Glessner’s journal.

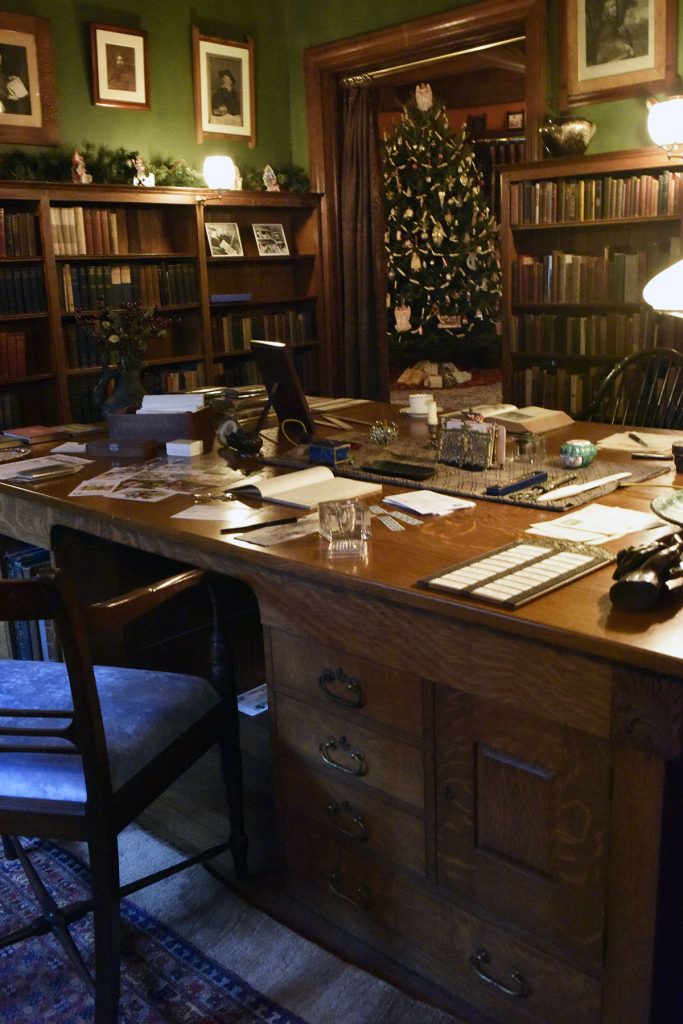

Preparing postcards in the library.

Servant gifts in the butler’s pantry.

In 1902 the journal refers to the lighting of the tree: “The children all came home Christmas morning at ten o’clock when we lighted the tree which stood in the hall.”

Tyre told us:

“In the tradition of the Glessner family, our tree has been shipped from The Rocks, a portion of which now operates as a Christmas tree farm. However, a serious fire at The Rocks earlier this year, made it impossible to ship a tree this year.”

Main hall and stairway.

We asked Tyre about Victorian tree trimming:

“The earliest decorations included strings of popcorn and cranberries. Cookies, nuts and other sweet treats were hung on the branches with a loop of string or thread. Fruit—a prized rarity before refrigeration—and unwrapped gifts were tucked into the branches of the tree. The fashion for making handmade Christmas decorations began in the mid 1800s and continued throughout the century. The painted walnuts and foil covered cardboard cutout bird seen on the schoolroom tree are typical of the homemade decorations of the period.

The original Glessner house ornament.

“We are fortunate to have one original Glessner Christmas tree ornament, returned by the family in December 2018. German in origin, and known as a “kugel,” the green glass ornament reads “1776” on one side and “1876” on the other, indicating it was made as a commemorative item for the U.S. centennial in 1876. It is probable that the Glessners purchased the ornament while visiting the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in August 1876. Glass ornaments were little known in the U.S. at this time, so it would have been quite a novelty. After the children both married in 1898, the Christmas ornaments were divided up between them. This ornament was passed down through George’s line of the family.”

Statue of Narcissus.

Parlor mantel.

Crafts on the parlor game table.

Literary salad.

The tradition of glass Christmas tree ornaments began in Lauscha, Germany in the late 16thcentury, consisting of garlands of glass beads that could be hung on trees. By the mid-19thcentury, the popularity of these decorations grew into the production of glass figures made by highly skilled artisans.

Tyre explained the process:

“The artisan heated a glass tube over a flame, then inserted the tube into a clay mold, blowing the heated glass to expand into the shape of the mold. After the glass cooled, a silver nitrate solution was swirled into it. After the nitrate solution dried, the ornament was hand-painted and topped with a cap and hook. In the 1840s, after a picture of Queen Victoria’s Christmas tree was shown in a London newspaper decorated with glass ornaments from her husband Prince Albert’s native Germany, Lauscha began exporting its products throughout Europe.

“In the 1880s, American Frank W. Woolworth discovered Lauscha’s glass ornaments during a visit to Germany and he made his fortune by importing these items to the United States.”

Fanny’s bedroom.

Packages were wrapped in wallpaper and sealed with candle wax. Commercially produced Christmas wrapping paper became available by 1910. On the Tuesday before Christmas in 1886, Frances Glessner wrote in her journal of “work[ing] all morning sending off Christmas presents.” Over the years there are countless December journal entries mentioning time spent preparing Christmas presents.

Wrapping gifts in the master bedroom.

Tyre told us:

“The custom of giving gifts at Christmas time began as a form of charitable piety during the Middle Ages when gifts were distributed to the poor. By the mid-19th century, Christmas gift-giving was promoted by ladies’ fairs as a religious and charitable act. Christmas gift-giving did not become widespread until the 1870s at which time gifts were placed unwrapped in the branches of the Christmas tree.

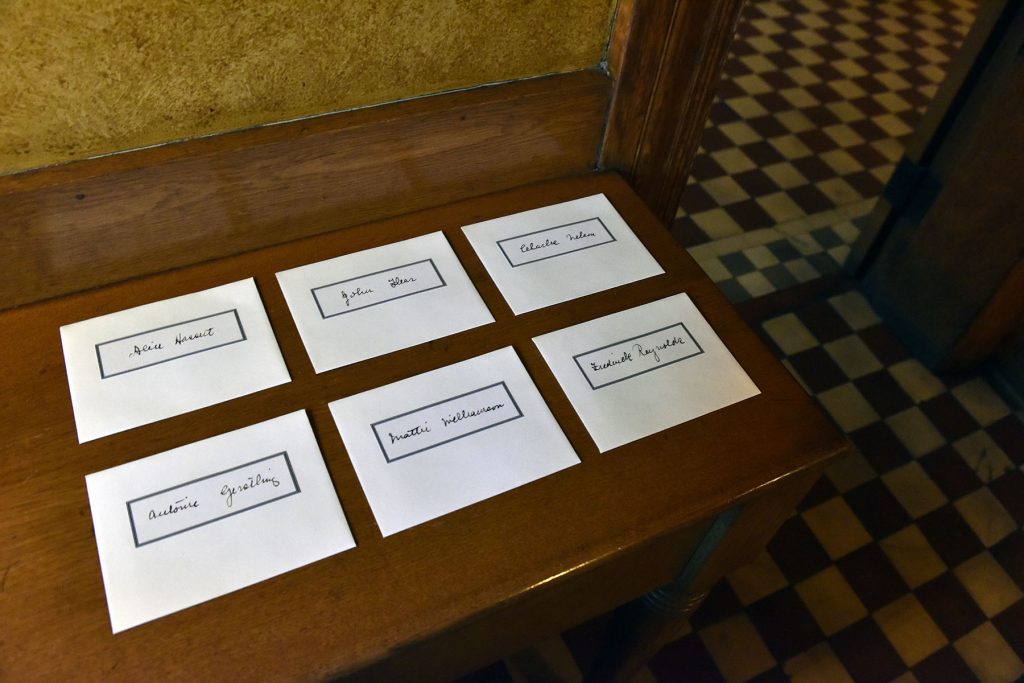

“The Victorians presented a wide array of Christmas gifts to friends and family. Presents such as doilies, silver tea balls and tea strainers for the hostess’ table were popular; and for the parlor there were photograph frames in silver, fabric, or leather. For the bedroom, suggested items were dressing table mirrors, boxes, fans, and jewelry. Gifts for men included cigars and cigarette cases, scarves and mufflers, umbrellas, and a good whip or carriage robe. Other popular gifts included flowers and gifts of food – preserves, jams, jellies and candy, often made the summer before.”

Dining room table.

Dessert table.

Some things never change at Christmastime, with children leaving treats for Santa and his reindeers before bedtime.

This note on the plate of cookies for Santa, written by Frances Glessner Lee’s daughter, a probably 7-year-old Frances Lee in about 1909, is preserved at the house:

“Dear Santa Clause – This year I want surprises. Thank you very much for the lovely presents you gave me last year. I wish you a merry Christmas and a happy new year, and please give my love to all the other children. Frances Lee.”

Preparing turkey in the kitchen.

Staging courses in the butler’s pantry.

Each year Frances Glessner prepared a “Christmas pie” containing small toys buried in rice with rhymes written on paper labels attached. Her journal entry in 1888 describes this tradition:

“We had a lovely Christmas pie covered with holly and smilax. The presents were buried in the tin pan in rice. We had a great deal of sport pulling them out, the labels hung out. There were rhymes on each one.”

We share some of Mrs. Glessner’s favorite recipes below which appear in The Prairie Avenue Cookbook along with favorite dishes of other prominent 19th century doyennes.

Photos by Kathy Cunningham

Drawing by Randy Jones

Pre-paid tickets are required. To learn more about the Candlelit Tours on December 21 visit: glessnerhouse.org