By Francesco Bianchini

Cape Cornwall

It has been widely proven that a disaster in the kitchen sometimes results in cherished memory. I have an abundant supply of such recollections, but the one I am about to relate to is very special to me. In December 1992 I departed Italy for the west coast of Cornwall with the intention of spending two months on my own. It is hard to imagine a world in which the resources we have today were not even imaginable. It was no joke to organize from a distance my stay in such an isolated and rural place. By mail, and also through an incalculable number of communications, I was finally able to reach a farmer who had a summer cottage a few hundred meters from the rough cliffs of Cape Cornwall. It was just what I was looking for, but I had to convince the man to rent me a house that was only equipped for summer living. Confronted with my obstinacy, the farmer promised he would do everything possible to make the place habitable that upcoming winter. I arrived from London on a gloomy afternoon. The farmer and his sons met me at a bus stop after an interminable journey because the usual train had been suspended due to heavy flooding in the south of England. The boys, ruddy from the cold, their tee-shirts snapping in the breeze, loaded my luggage into the car, and off we went under scudding clouds along lanes half-hidden by gorse bending in the wind.

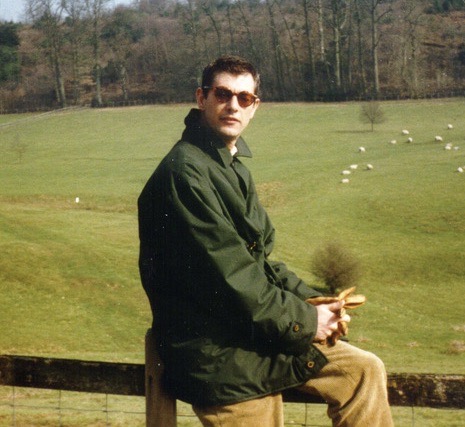

Dressed for a Cornish Winter

The house proved more spartan than I had contemplated: the only room retaining a certain warmth was the living room, with its large stone fireplace housing an electric heater that simulated a crackling log fire. In the bathroom and the kitchen it was necessary to switch the electric radiators on by means of cords hanging from the ceilings. In the corridor, also heated by night-time storage radiators, the temperature never exceeded ten degrees. In the bedroom, in addition to a pile of goose down comforters, I found an unusual item of comfort: a combination radio, alarm clock and teapot occupied the top of the bedside table. At six in the morning the radio came on, tuned to the third BBC channel, while the kettle dripped water into the cup for brewing. In the evening I snuggled under the blankets, two fingers pocking out to hold my book. I fell asleep to the whistle of the wind, the tapping of the rain on the roof, the thud of the breakers against the cliff, dreaming of sailing ships tossed at the mercy of storms, and of French lieutenants’ women scanning the horizons.

The Farm

So began my period of isolation, punctuated by the jingle of coins swallowed by the electric meter, and cheered by the unexpected company of Buster, the farm’s border collie. The dog was not allowed in the main house and I pitied seeing him wandering around the yard in the cold wind and rain. When I opened the cottage door to let him in, he knew we were both breaking the rules. Buster waited patiently for me to spread a waterproof sheet in front of the fireplace before snuggling there. If he appeared at my window on a rainy afternoon, hair glued to his nose – just a flash, as he wasn’t a dog to beg attention – I couldn’t resist. Buster became my walking companion. Whenever I left the house, armed by rubber boots and an oilskin coat, he carefully followed my movements, ears perked. When I climbed low walls in the direction of the village he sadly returned to his kennel, but if I headed toward the lighthouse, he galloped ahead on the grassy path, descending the edge of the cliff to the sea-tossed cove below. There he would wait, his muzzle challenging the wind.

My Friend Buster

As Christmas approached – my first away from family and completely alone – I decorated my little house with branches of gorse and holly. I bought a free-range chicken from a nearby farm, and from a cart at the end of the drive, bought apples, onions, potatoes, turnips and cabbage. Little more than a beginner in the kitchen, I set myself to the task of preparing a regal and festive meal. In the kitchen I sauteed the pippin apples in butter, brown sugar, salt and garlic cloves, filling the cottage with spicy fragrances. I gutted and cleaned the chicken, but stuffed it in front of the television in the lounge with Handel’s Messiah blaring live from Dublin, the 250th anniversary of its first performance. I placed the chicken in the baking dish with the cooking juices, closed it with toothpicks, flecked it with butter and cinnamon, and threw on the rest of the sliced apples and a few wedges of mandarin orange. It was ready to cook. But what I had not considered was the size of the oven compared to the size of the bird. Although I had chosen a modest specimen, I was forced to tie it up in the recommended position for an emergency landing. Enjoyable aromas wafted down the Siberian corridor from beyond the closed doors to where I sat, listening to the crescendo of the concert. Returning to the kitchen, I was shocked to find the oven door ajar. What had happened? The string had burnt, freeing a thigh from its ankylosed position, and it had kicked open the door. It didn’t seem like the end of the world; the smell was delicious and the bird looked inviting. I set the table and uncorked a nice bottle of red wine from Puglia. The first bite, under the golden crust, was promising – but as I cut further down, I found the meat was as firm as the leg that had protruded from the door. Practically raw, definitely inedible. At that point Buster, standing on his paws, peeped in the window. At least the dog would get a mouth-watering feast.

My Christmas Wreath