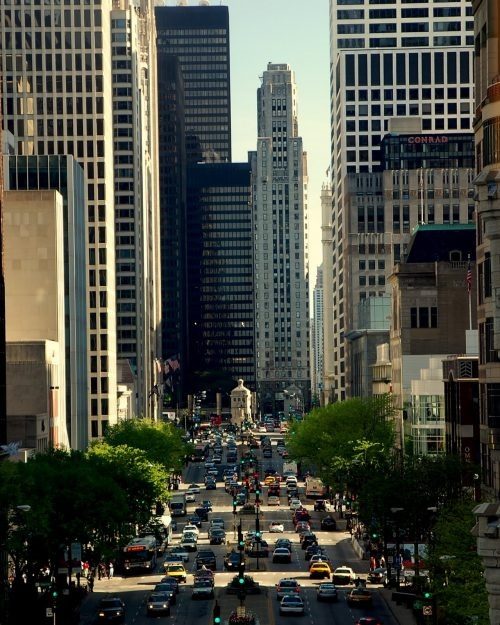

Photo Credit: Robert Whitfield

By Megan McKinney

“Inevitable” was the word used by its early 19th century boosters to describe Chicago’s future as the metropolis of the northwestern frontier. This, however, would have been an imprecise appraisal. Chicago’s dazzling future existed, more exactly, in the energy, courage and determination of a handful of self-made young men from New York State and New England.

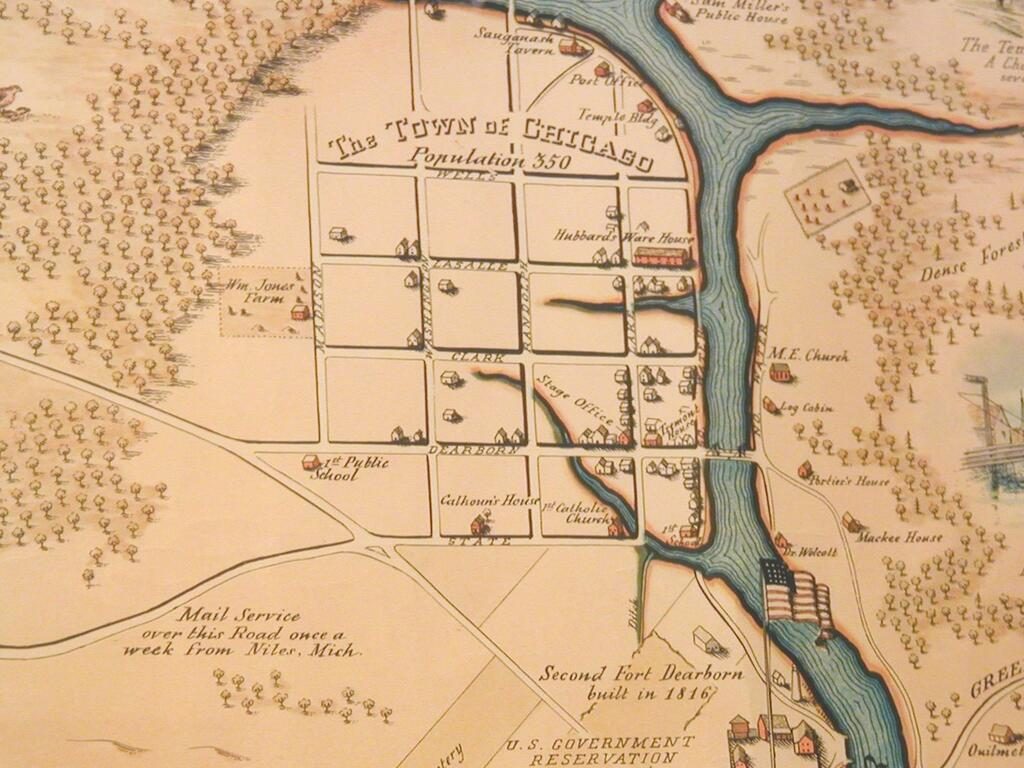

Before it became Chicago, the site at the intersection of Lake Michigan and the Chicago River was a Potawatomi village.

Before it became Chicago, the site at the intersection of Lake Michigan and the Chicago River was a Potawatomi village.

The adventurous young Easterners, most often farmers’ sons who didn’t wish to farm, massaged and manipulated the site’s imperfect geography to create a stage for the city’s unimaginable mid- to late- century explosion into prosperity—a prosperity that would create the earliest of Chicago’s great fortunes and family dynasties, some of which continue to prevail more than a century and a half later.

The Potawatomi Treaty of September 1833 transferred the last of Native American ownership to the United States government and the Chicago Potawatomi moved west.

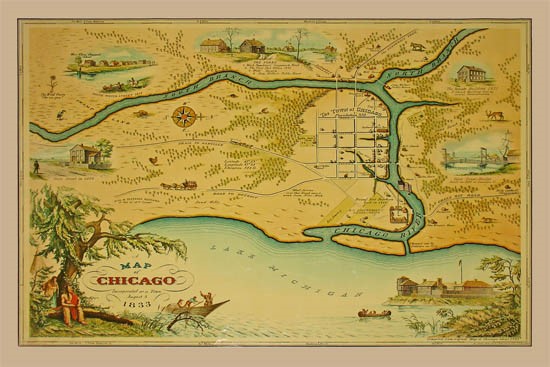

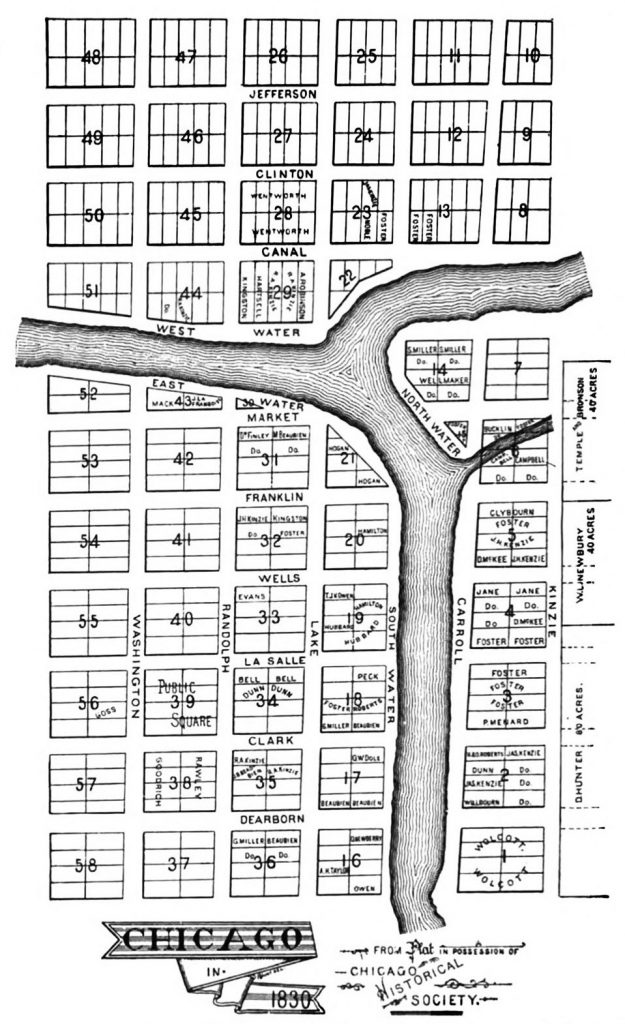

Map of Chicago in 1833; population 350.

Map of Chicago in 1833; population 350.

While its site was tantalizingly close to the point at which the continent’s two crucial systems of water might connect, Chicago was virtually isolated. The embryonic city at the juncture of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan was not only challenging to reach, either by water or land, but it was also a soggy swampland initially thought to be uninhabitable.

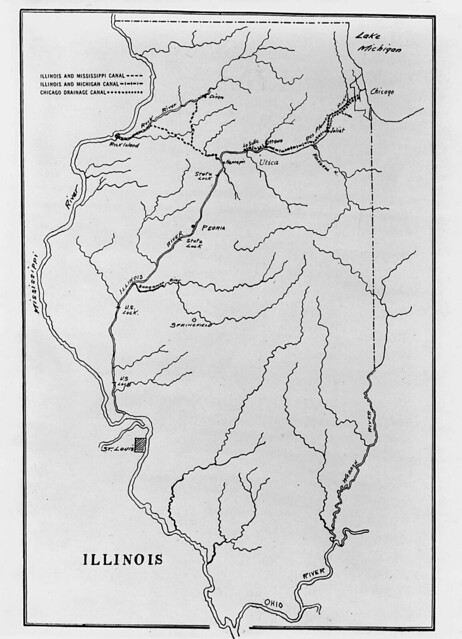

The Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, so close and yet . . .

The Chicago River provided a channel to the Great Lakes; however, there was no clear water passage connecting it to the Illinois River and thus with the great Mississippi. Furthermore, a sandbar blocked entry of larger vessels from Lake Michigan to the Chicago River. However, optimism and enterprise triumphed, and, by 1834, a channel had been cut through the sandbar.

The sandbar at the mouth of the Chicago River was described as having the appearance of an elephant’s trunk.

Although a man-made aquatic strip connecting the two great bodies of water had been visualized by French explorers as early as the 1670s, it was another century and half before the United States considered this a way to develop the new country’s vast interior. In 1822, Congress granted Illinois a band of land for a canal; however, even then, it took time to raise capital to pay for construction.

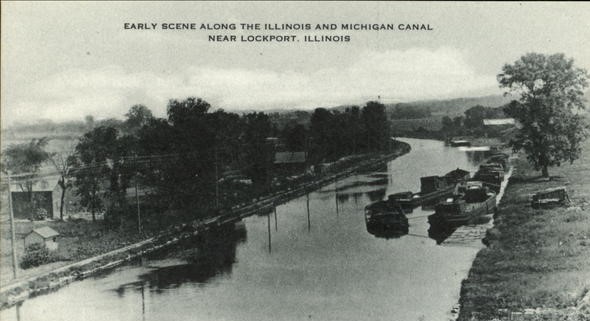

The 96-mile Illinois and Michigan Canal was constructed between Bridgeport in Chicago and the Illinois River at LaSalle, Illinois, completing the connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

In this depiction of the canal location, it is hidden under the orange ball.

The canal land grant consisted of alternate square-mile sections of land in a strip along the canal roughly 10 miles wide and 90 miles long. Illinois and Michigan Canal commissioners made the first plat of Chicago in 1830 and sales continued to repay the cost of the building the canal after its mid-19th century completion.

To finance construction, the federal government also designated large chunks of public land as “canal lots” to be sold in an escalating real estate market as Eastern financiers began speculating on the swampy land. This was Chicago’s first boom, creating a mania of canal lot investment.

The completed canal.

The long anticipated body of water opened in 1848, at last, connecting the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers with the Chicago River—and thus Lake Michigan. It was then, and only then, that Chicago became “inevitable.”

Coming up: Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasties will begin a series on Chicago’s first great dynasty, the Ogdens—and the McClurgs.

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl