By Francesco Bianchini

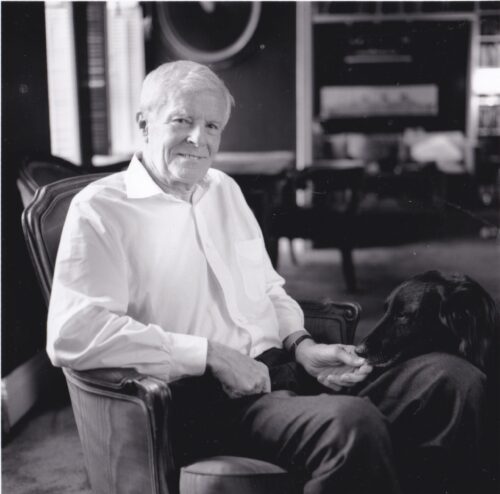

I was well into my thirties when I met him; to everyone he was ‘Van’ even though his given name was the more ponderous ‘Van der Veer’. We were at least forty years apart in age, and a stroke had compromised his ability to speak. He struggled with words; his diction was indistinct and slurred, a heavy handicap for someone who, as editor-in-chief of an important national magazine, had built his career on words. Yet most of the time, when Van couldn’t finish a sentence, he laughed as if fate was playing a prank. I learned to understand him and to anticipate what he had in mind. His habit of stripping a page of everything superfluous led him to limit his interventions to what was strictly necessary, and to be more willing to listen. For the rest, he was still an inquisitive, passionate, independent man, who inspired sympathy in anyone who came across him, and gave a glimpse of the truly awesome guy he’d been. And he was still surrounded by friends who – some for one reason, some for another – had contributed to the cultural vitality of New York from the post-WWII period to the mid-80s. Van had been a close friend of Howard Moss, for forty glorious years editor-in-chief of The New Yorker poetry section, as well as Daniel’s Pygmalion and companion – my first American boyfriend. That’s why, that’s how, I made Van’s acquaintance in a scorching American summer at the end of the 20th century. If I remember him today, it’s because he was the doting grandfather and uncle I’d never had.

Van der Veer Varner (1924-2008) and his dog Shep

Van lived in an iconic pre-war skyscraper on Central Park at the corner with the Museum of Natural History – the place where young Holden Caulfield returned to find the enchantment of his adolescence intact. For ten years, until Van’s death, that address was my home whenever I visited the city, and I got to know all its recesses: its various entrances with their sleek towers of fresh flowers; the service staircases and elevators; the immense and disquieting basements with bike sheds, utility rooms, and laundries; the faces of doormen, elevator operators, maintenance workers. I loved the building’s bulky profile, with its turrets soaring above the treetops of Central Park from whatever angle you looked. Following Van’s dog through the dark corners of the park on our evening strolls, the edifice shimmered with the lights of its twenty-three stories, emanating a sense of comfort and solidity, like a stronghold keeping watchful eyes on us. And a stronghold it was in the truest sense; the only house, in fact, to which I needn’t carry a key. No stranger dared sneak by the doormen unannounced – which is why Van’s apartment door was never locked.

A touch of class on Central Park West

Van had moved to the Upper West Side in the 1970s, when fashionable interior designers loved to paint walls in dark colors – plum and eggplant, even pitch black – to highlight metal and chrome, yet his apartment – a green so dense to seem black – was furnished with sober Empire pieces, including a boat bed nicknamed ‘Carlotta’s’ because it had, indeed, belonged to the unfortunate Empress of Mexico. The ensemble was beginning to show its age, as was Van’s wardrobe, but he didn’t seem to care. His passions were ocean liners, horses – a true Kentuckian at heart – and theater shows, and he loved to share them. Together we’d go to eleven a.m. movies at Lincoln Center, or to afternoon shows at Broadway music halls. He introduced me to the older hits, like South Pacific, Annie Get Your Gun, and my favorite, Cole Porter’s 50 Million Frenchmen. Van also took me to horse racing at Belmont and Aqueduct where we’d rigorously wear coats and ties – but we got there on public transportation. He was happy to explain how race sheets worked, but I had no head for strategies and combinations, nor patience even to read the program. I bet at random on horses whose names tickled my fancy – Lulu’s In Charge, Betcha By Golly, Blind Ambition. Van collected his winnings with the enthusiasm of a young boy, even though the best seats in the stands, and the refreshments in the elegant dining room reserved for members, cost him far more than he won. The staff recognized him and treated him with special care and kindness – not because he exuded any social prestige, for Van was not a rich or powerful man – not by New York standards, at any rate – but they saluted in him a dying all-American grace. To everyone he was the Southern Gentleman who smiled at life and had a frank word of kindness for everyone, an Ashley Wilkes or an Atticus Finch; a rare commodity in a world increasingly subjugated by arrogance and vulgar coarseness. In the elevators he reserved the same cordiality for the rich and famous residents of his building as he did for the young man who operated it.

My castle in Manhattan (photo by Zal Latzkovich)

I haven’t met anyone as disinterested in food. For Van, eating was either a purely utilitarian matter or an inescapable social duty – but in both cases personal gratification was not part of the equation. He, who happily spent his savings on luxurious cruises, plays, and horse races, became stingy when it came to eating, and he was generally content to order obscene pizzas for delivery from Pizza Uno, or take-out dinners from a nearby cheap Chinese place called the Silk Road Palace. When in New York, I loved making the rounds of the neighborhood’s fine food stores, then cooking in Van’s kitchen that hadn’t been remodeled since the 1970s, and setting the table with his magnificent china, crystal and silverware he’d inherited from his mother. Van liked to sit on a stool and watch me without saying anything, but his smile – I knew – meant ‘so much trouble to put food on the table!’ To keep him happy I’d appeal to his easy childish tastes and never fail to buy ice cream on my way home, or whip up a pineapple upside down cake that made him squeal with pleasure.

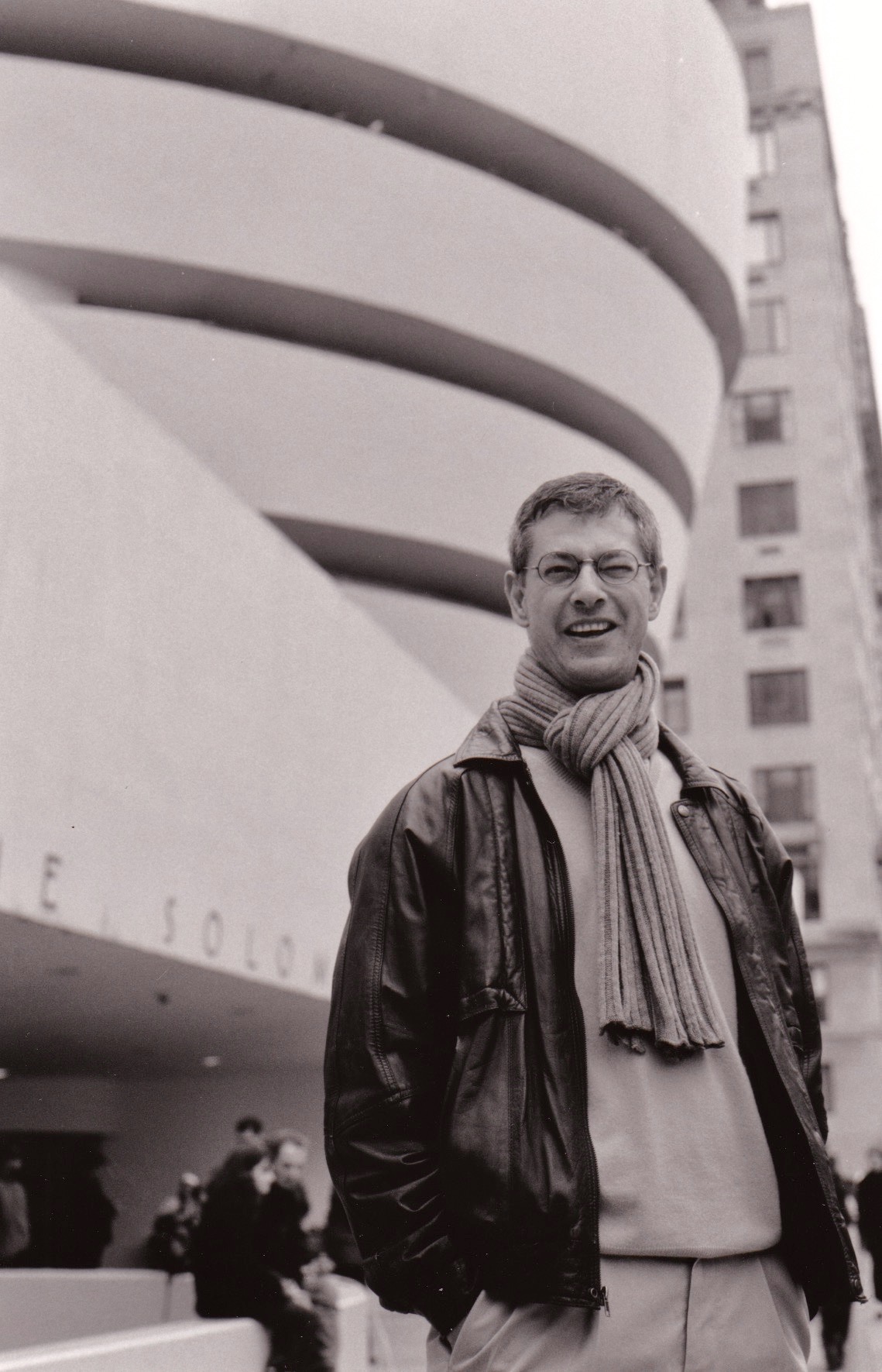

Out and about in NYC