By Brigitte Treumann

In these days of strange confinement, travel bans, at-home-sheltering, virtual meetings with family and friends, I seek refuge in my diaries and extensive photo files from past travels far and wide. Today I would like to share some memories and highlights of an extensive and intensive sojourn in Egypt in January 2006. It all began with an invitation from an Oriental Institute classmate, dear friend, and distinguished Egyptologist, Edward Brovarski, who co-directed a joint expedition and salvage excavation of Cairo University and Brown University in the so-called Abu Bakr cemetery on the Giza plateau, west of the 4. Dynasty Pharaoh Khufu’s (Cheops) pyramid While I had spent much time working in other parts of the Levant, Egypt had so far eluded me and I accepted Ed’s invitation with alacrity, looking much forward to spending time with him and his team, but also to freely wander through thousands of years of ancient Egypt. That sounds rather pompous but it is exactly what I did. I crisscrossed the country by car, felucca (the lateen-sailed, oar-propelled Nile vessel), dingy little motorboats, and, last but not least, on foot.

Happy wanderer in the Theban mountains

I remember, with great joy, my day-long hikes through the west bank of the Nile from Medinet Habu, located across the Nile from Luxor, to visit the spectacular Ramesside mortuary temples (Ramses II; Ramses III 19. And 20. Dynasties respectively) to the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari where some of the most stunning examples of ancient Egyptian architecture are located: the terraced temple of Mentuhotep II (11. Dynasty) though only vestiges of the grand design survive, and the masterwork of Queen Hatchepsut’s (18. Dynasty) chancellor and architect, Senenmut, her majestic mortuary temple.

Outstanding details of Ramesside architecture

Column in the Hathor chapel of Queen Hatchepsut temple

Portrait of Senenmut

Another day-long hike took me to the Valley of Kings ( if memory serves, I walked into every tomb that was open to the public), and then took a detour, with a glance at the Worker’s Village at Deir El-Medina,(once inhabited by the workers who built and decorated the tombs of the Valley of the Kings), back to Sheikh El-Qurna, the name of the hillside village built over an extensive necropolis of private tombs dug into the soft limestone. Many of these “Tombs of the Nobles,“ are still well preserved; their extensively frescoed walls are often stunningly beautiful and “take their rightful place among the masterpieces of New Kingdom art.” (18. – 20. Dynasties). I remember at the end of that long day, sitting with a jolly crew of guards, drinking apple tea and socializing with my guards.

Wandering in the Valley of the Kings

Socializing with my dominoes-playing guards

Backtracking a bit it amuses me to think of my seemingly adventurous arrival in Cairo airport in the middle of the night. Will the driver be there to pick me up? Will we find each other at 2 am in the busy arrival hall? Had my luggage arrived with me? It all fell into place. The kindly driver was waiting, my capacious backpack arrived and so we drove through the night to the “dig-villa” (the expedition’s headquarters) in suburban Giza. We got to the place, Samvel the driver, unloaded my luggage, and bid me goodnight. I stood in front of a wall and a solid tall metal gate that was firmly and impenetrably closed, no bell to ring, not a soul in sight, not even a passing car. Calling for the watchman was to no avail. I began to wonder whether I would spend the night outside, crouching on my luggage. But, finally, insistent yelling and banging on the metal door brought my friend Ed to the rescue. He proffered a welcome hug, hot apple tea, and a sandwich and sent me off to my designated bed-chamber.

The next day, the last day of 2006. we drove up to the Abu Bakr cemetery where Ed gave a lecture on his work and the significance of the site. And I could actually touch, just a little bit, the rough stony surface of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, Khufu’s Great Pyramid. At night we toasted the New Year under a brilliant starry sky with the faint silhouette of the Great Pyramid as the perfect backdrop.

Our mudir (director) Ed Brovarski at the Abu Bakr cemetery (Photo: Marianne Barcellona)

The famous “Khufu Ship” or solar bark, assumed to have been built for Pharaoh Khufu

The Great Pyramid

The Giza Desert plateau is essentially a vast royal necropolis of the Old Kingdom where not only and most prominently the pyramids stand proudly, but a multitude of courtly tombs, burials of royal spouses and children, mortuary temples and the magnificent sphinx cover the expanse of the plateau and its hillsides. I have spent many times walking around there, not only on this trip, and each visit revealed a new monument, a tomb I had not seen before, a vista not beheld. But the great event of my 1st of January 2006 was to actually enter the Great Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops) – to walk a long stretch of interior corridors. To feel those walls around you, to truly walk (or crouch-walk since I am much taller than the average ancient Egyptian) inside a nearly 5000-year-old structure was breathtaking in every sense of the word.

The Sphinx in front of the Chephren pyramid

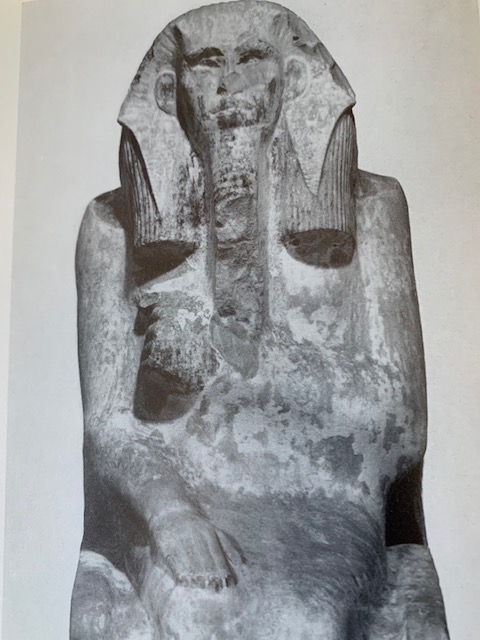

But nothing quite compares to the first glimpse I had at the site of Sakkara, some 30 km south of Giza, of the honey-colored, anciently-silent, desert-surrounded funerary complex of King Djoser, the Great Old Man of the 3rd Dynasty. I had seen his life-size statue in the Archaeological Museum in Cairo, and I was struck then by his peculiarly prophetic gaze and features that are quite distinct from his successors, or that of the canon of royal portraiture that emerged in successive millennia.

Close-up of the great Pharaoh Djoser

Statue of the great Pharaoh Djoser

He, or rather his brilliant architect, Imhotep, designed what we call the Step Pyramid, Djoser’s royal tomb, the unique forerunner of the classic Egyptian pyramidal shape. It is strictly speaking not a pyramid, but a structure of mastaba tomb, (a flat-roofed, rectangular structure made of mudbricks) one stacked upon the other, but so ingeniously constructed that it does have the appearance of a pyramid. Through the millennia, the step-pyramid has somewhat crumbled and lost its original outer mantle of limestone slabs. But there it is, still, sitting among remnants of wonderful limestone enclosures, walls decorated with friezes adorned with rearing cobras, chapels and festival temples, all created by the formidable chancellor and master-builder of the early 3rd millennium BC, Imhotep.

The Djoser Step Pyramid

One of the Heb-Sed Festival Temples

The amazing cobra frieze

The rearing cobra or Uraeus represents the protective goddess Wadjet who was, as we would say, the patron saint of Lower Egypt. In time the Uraeus came to signify the consummate symbol of royalty and the prominent visual element attached to the royal crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Sakkara is, much like Giza, a vast necropolis dotted with pyramids (but none as prominent as the Djoser Step Pyramid) and mastaba tombs of prominent courtiers. I had the good fortune to be allowed to enter the mastaba of Mereruka, a high official from the 6th Dynasty, one of the most wondrous private villa-like tombs, close to the Djoser complex. As you wander around in the many chambers, their walls decorated with lively scenes in painted relief from the owner’s daily life, you quite unexpectedly “meet” the life-size figure of Mereruka, stepping out of a doorframe, dressed in a short loincloth, looking self-assured and regal. It was a mildly shocking experience to have a 4000- year old viceroy staring at you. Unfortunately, we were not allowed to photograph, so the viceregal stare must be imagined.

Needing a break from tombs, chapels, and temples, I flew to Luxor to meet up with Father Nile. Luxor was the ancient city of Thebes, capital of Upper Egypt during the New Kingdom and is, besides a charming lively contemporary town, the site of some of the greatest monuments of that era. Any guidebook worth its salt will expand on the overwhelming complex of temples at Karnak, the formidable Temple of Luxor, the museums and, of course, the west bank that I spoke of earlier and that I loved exploring on foot.

I was now eager to explore the Large River, the live-giving stream without which there would be no Egypt, ancient or modern. A friendly and sophisticated travel agent put me in touch with one of the many felucca owners, a particularly charming and knowledgeable young man, Capt’n Moussa, as he called himself.

Capt’n Moussa

I climbed on board, the lateen sails were hoisted and a gentle breeze moved us up-river. It was one of the loveliest experiences I ever had, leaning back, observing white herons floating above us, peaceful vistas of palm groves and flowering bushes on the proximal riverbanks, daydreaming in the lingering afternoon. Capt’n Moussa regaled me with river stories, true or invented. it made no difference. All was peaceful.

Rivergirl

The great lateen sail

Riverscapes near and far

This riverine excursion was so delightful that I arranged for another outing. The excavation team from Giza had come to Luxor the night before, a reunion we celebrated in a romantic outdoor restaurant by the riverside. I mentioned Capt’n Moussa and his wonderful felucca and would they like to sail upriver with me. And so we did – a very joyful and convivial group we were – Musa had brought snacks and iced tea and we happily sang, “Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream, merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream. “

What a perfect coda to the first week of that fantastic trip these many years ago. Some of us have stayed in touch and we always send a grateful thought to Capt’n Moussa and his gorgeous felucca.

The merry band on the Nile (Photo: Marianne Barcellona)

An approximate timeline of a very long history

Old Kingdom (B.C. 2778 – 2263)

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

First Intermediate Period (B.C. 2263 – 2133)

7. -10. Dynasty

Middle Kingdom (B.C. 2133 – 1786)

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

Second Intermediate Period (B.C.1786 – 1552)

- – 17. Dynasty

New Kingdom (B.C. 1552 – 1085)

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

- Dynasty

Third Intermediate Period (B.C. 1085 – 332)

- -31. Dynasty