By Francesco Bianchini

I spent my freshman year at an experimental university in Pescia, a Tuscan town in the province of Pistoia, famous for its carnations. It was my father’s idea. Professors from the universities in Pisa and Florence – attracted by the novelty of it all – came to give lessons to a handful of us, inmates studying in the ancient cells of a Poor Clare convent. Pescia had nothing at all to animate a student’s life. In the intentions of the founders that was, perhaps, a good thing: no distractions to disrupt serious studies in political and social sciences.

As I’d anxiously awaited the moment I could flee far from home, however, I’d imagined my escape in more dazzling color: green riversides shaded by majestic silver beeches, framing the spires of soaring Gothic buildings; smoky cafes enlivened by late-night chats; romantic attics inhabited by young people like me, intoxicated by life and poetry.

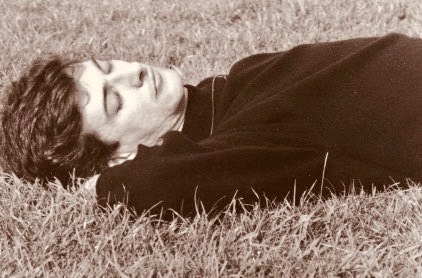

In my field of dreams

While waiting for the convent to be equipped with a dormitory for students, my parents placed me in the care of an elderly widow. That lady put at my disposal a dark room overlooking an alley, with a bathroom shared by another lodger – a taciturn office worker – plus the use of the same kitchen where the landlady spent most of the day, and from which she kept an eagle eye on our comings and goings. At the end of every month, she intercepted me with a grin that barely concealed her wheedling tone: when would I be handing over her ‘nickels and dimes’?

It was first time I’d been on my own and I can’t say I was able to give my best to domestic chores. The kitchen was heated by a stufa economica whose pipes snaked in all directions before disappearing between the beams of the ceiling. And it was there I sautéed hot dogs, prepared freeze-dried soups, toasted bread for bruschetta, or fried eggs in a pan. The old woman watched my preparations from her corner armchair, invariably tottering up to poke her sharp nose over my plate, which I tried to arrange in the least disheartening way. Inhaling the aromas, she’d ooh and aah in what sounded like malevolent condescension. Occasionally a friend of hers would visit and together they’d spend the evening ruminating in the gloom, glancing my way, and hissing inaudible conversations over the hum of a television set.

The stufa economica of yesteryear

I rarely lingered beyond the time necessary to eat my dinner; just cleared the table, and speedily retired to my room – a tiny space poorly divided by a partition which, on occasion one assumed, could accommodate a second person. That other half served me as a study even though – with no windows, and only a fanlight between the wall and ceiling – it was necessary to keep a lamp on both day and night. A lacquered cherry wood armoire there saturated my clothes with the stench of mothballs, left to disintegrate since time immemorial, and I studied with a heater on, listening alternately to Billy Joel, Loredana Bertè, or Rachmaninov on a cassette player.

I was reading Dostoevsky, and with dreamlike participation let myself be so engaged by his oppressive and desperate atmosphere, that I fantasized about freeing the world of the old woman’s unpleasantness by doing away with her completely with the very knife she kept for scaling fish. And for good measure, I’d include her sidekick too, who – unfortunately for her – would blunder onto the scene at the wrong time.

During the week, lunches arrived at the university in aluminum containers, thanks to an agreement with the local school cafeteria. Sometimes joined by our professors, we students sat at tables made of formica in the barren convent refectory that soon filled with the fumes, say, of roasted chicken, green beans, and boiled potatoes.

To continue playing the piano, I cajoled a set of house keys from a distant relative who lived in a palazzo halfway down Pescia’s long square – the central one framed by buildings plastered in the enchanting mottled yellows and browns of Tuscany. Since she much preferred life in the country, I spent lonely afternoons tinkering in the living room into which she seldom let air, and that smelled of musty upholstery.

|

My cousin’s palazzo, halfway down the long main square |

One end of Pescia’s central square |

A certain languor, propelled by my austere diet, drew me to her pantry and refrigerator, both stocked with delicious produce from this cousin’s farms. Desperate to afford cigarettes and a few weekly outings, I plundered her kitchen hoping that my petty thefts were sufficiently inconspicuous – especially since she had a tendency to obesity and, being quite old, certainly ought not gorge herself on cheese, eggs, and salami.

My classmates included some young people from the surrounding provinces – but they were a closed and separate clique. We out-of-towners were a polyglot group with anomalous backgrounds: a girl from Sicily, one from Genoa, another from Piedmont, an American guy, and even a boy from Peru. Misfits, we met regularly at a trattoria called La Buca – ‘the hole’ – which was housed at the bottom of steep steps on one end of the square. For only the equivalent of about five dollars you were entitled to the dish of the day, and an all-you-can-eat appetizer buffet.

Among the many dishes, I never passed up was La Buca’s smoked herring and onions, slathered in sour cream – something which in the culinary temple of Tuscany would be considered, like our group, a perfect intruder, and whose pungent fumes overpowered the others: sauces of giblets, bruschetta smothered with tomatoes and fine Tuscan oil, tripes perfumed with bay leaves, chick pea flatbread called cecina, polenta with sausages, pecorino di Pienza, and various cold cuts. The taste of herring and onion clung in my mouth for a long time afterwards, leaving me quite thankful that the romantic encounters for which I yearned should have to wait a little while longer.

My favorite: smoked herring, onion and sour cream dip