By Megan McKinney

All the guardian angels had been at the 1866 christening of Ford Ferguson Harvey, bestowing upon Fred and Sally’s oldest child every gift for which doting parents might have hoped–charm, intelligence, great looks and, possibly most of all, diligence. Yet in the midst of academic honors the 19-year-old was receiving from Racine College, his father insisted he drop out of school to begin learning the Harvey business. He was to do this by following his father day by day both in Leavenworth and on his almost constant travels aboard the Santa Fe.

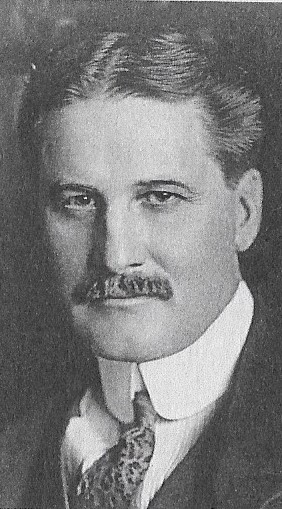

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Ford, the Harvey’s golden boy.

But it wasn’t only his father Ford began shadowing. Another of Fred’s inexplicable Tom Gable-style hires had occurred one day in 1881, when he walked into a Leavenworth bank and asked his favorite teller, 22-year-old David Benjamin, to work full time as his accountant. Tom Gable may have inspired the soon to become indispensable Harvey Girls, but it was Benjamin himself who would be crucial to the organization.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Dave Benjamin.

At Fred’s request, Dave became the company’s business manager and was moved to Kansas City, where he set up the central office, while working his way toward becoming the number two man in the Fred Harvey empire. Therefore, by the time Ford was seriously learning the family business, the second most appropriate man to shadow was Dave, which he did with increasing frequency. Also in the mix of Ford’s impressive mentors was “Uncle Bill,” the powerful Santa Fe President William B. Strong, whose home base in Wisconsin helped explain the nearby Racine College as Fred Harvey’s higher education choice for his gifted son.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Judy Blair and Ford Harvey

In 1888, Ford married the great love of his young life, Josephine “Judy” Blair, daughter of a prominent Leavenworth lawyer. According to Fred Harvey biographer Stephen Fried in his superb 2010 book, Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West—One Meal at a Time, the Blairs were considered “old money” vis-à-vis the “nouveau riche” Harveys. Judy was 21; Ford, 22. Judy was Catholic and Ford, Episcopalian. Although Ford did not convert, their children would be raised as Catholics without opposition. Following a honeymoon at Chicago’s Palmer House, the couple settled in their new home in Kansas City, where they were soon to become among the city’s leading citizens. Although Judy traveled incessantly and the workaholic Ford stayed close to the office, their’s was a stable marriage. Their children were Kitty, born in July 1892, and Freddy, January 1896.

Patriarch Fred Harvey, in spite of his frenetic, on-the-run lifestyle, was never entirely well following his near fatal yellow fever bout as a young man. He was always in search of any sort of medical help—much of it untraditional, so it wasn’t surprising that in late middle age—with his business matured—Fred spent months at a time in his native England seeking cures there. In October 1899, at 63, he at last obtained not a cure from a famous English physician, but a firm diagnosis, followed by drastic surgery. Fred had colon cancer, according the great British surgeon Sir Frederick Treves, who made the diagnosis and performed the surgery.

Sir Frederick Treves

After a convalescence of several months in England, Fred returned to America in May. He would spend a last Christmas with his family at the house in Leavenworth before traveling out by private Santa Fe car to warmth and further medical possibilities in California.

When Pasadena doctors gave no hope for improvement, Fred made the three day journey home by private Pullman on the California Limited, which did not make meal stops. However, employees at every Fred Harvey eating house along the way knew he was on the train and were aware of his tenuous condition; when the train stopped at stations to pick up passengers, Harvey Girls, busboys and chefs stood nearby in respectful silence.

A typical AT&SF train station in Barstow, California.

When Fred Harvey’s life ended in early 1901, the company he left was operating properties—including 45 restaurants—in a dozen states, and managing 20 dining cars. But Fred really didn’t “leave” anything, and he wouldn’t for another decade. According to his will, everything was to continue as if he were alive. The company, which had in recent years been guided by Ford, Dave Benjamin and a few others, with Fred’s son-in-law, John Huckel, operating the extensive and lucrative newsstands division, must not change, nor should his household.

The handsome house in Leavenworth would later become a tourist attraction.

His family was to remain in the same house, for example, with current servants staying on. At the end of ten years, the estate would be split in two, with one half going to Sally and the other divided among his children.

Another continuation of the current status–not Fred’s decision, but an agreement among those who were operating the company before and after his death–was that its name would be Fred Harvey and nothing more. Travelers were not being served by the Fred Harvey Company or equivalent name, they were in the care of Fred Harvey. Again, it was as though he had never left.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Ford Harvey in his maturity.

The year of Fred’s death, 1901, was the year his 35 year-old son Ford encountered the closest brush he would ever have with a religious experience, his first view of the Grand Canyon.

It is an awesome experience for any human being and far too immense, varied and spectacular to be captured in a single photograph. At the time of Ford’s first sighting, the great geological wonder was an obscure, somewhat eccentric destination for travelers; however, within ten years, it had become the nation’s “premier natural tourist attraction,” with more than 30,000 visitors traveling there to experience its unique grandeur annually. And seated directly on the Canyon’s South Rim, reigning over it all, was El Tovar, a hotel operated from its January, 1905 opening by Ford on behalf of Fred Harvey.

El Tovar is believed to continue to be “the most in-demand hotel in the world” today, with rooms booked more than a year in advance by people who plan holidays based on the availability of those rooms.

The spectacularly popular El Tovar.

Classic Chicago readers who are enjoying our Fred Harvey series will be interested in the 2020 Fred Harvey History Weekend. Here is the link to learn about the annual November event–virtual this year–which is hosted by Fred Harvey authority Stephen Fried. https://www.eventbrite.com/e/fred-harvey-history-weekend-2020-online-6-talks-over-3-days-tickets-123954365845

Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasties series on the Fred Harvey family will continue next with Inventing an Alternative Fred Harvey.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl