By David A. F. Sweet

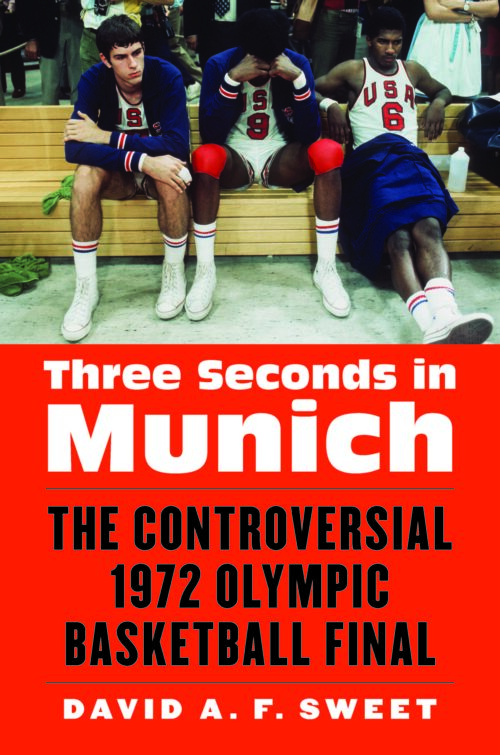

Editor’s Note: The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet wrote the book Three Seconds in Munich. On September 9, 1972, the USA Olympic basketball team essentially won the gold-medal game twice before the Soviet Union sank the final basket. What happened? The head of international basketball kept putting time on the clock — illegally. The 12 Americans became the only Olympic athletes to reject their medals — a half century later, they still refuse to accept them. In an Olympics marred by the brutal murders of Israeli athletes and coaches, read the excerpt below to see how Doug Collins gave the United States the lead with three seconds left before chaos and corruption struck.

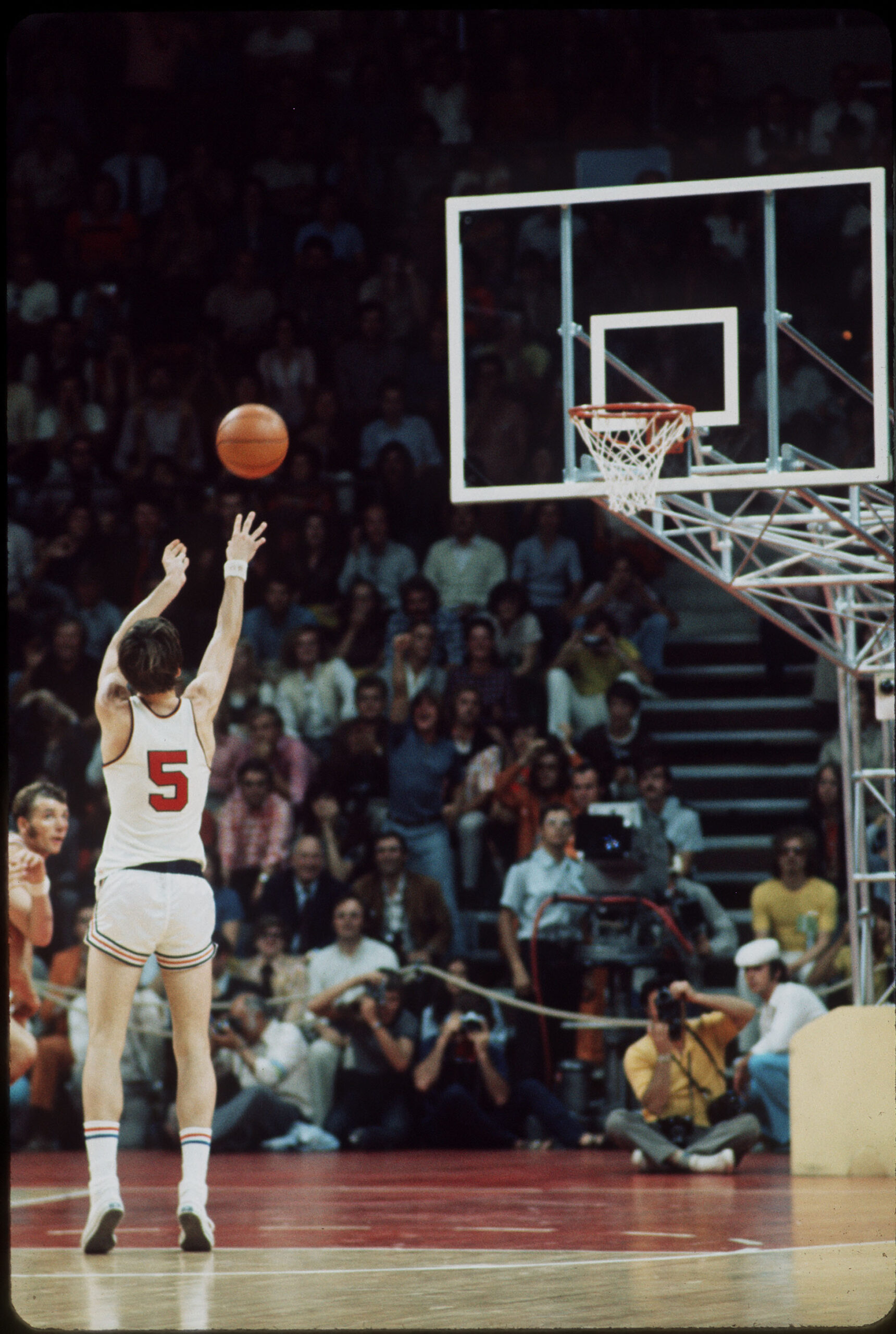

Doug Collins sank two of the most pressure-packed free throws in Olympic history to put the United States ahead in the gold-medal game.

Excerpted from Three Seconds in Munich: The Controversial 1972 Olympic Basketball Final by David A. F. Sweet by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2019 by David A. F. Sweet.

Hornswoggled

If anyone had told a knowledgeable basketball coach at the 1968 games that Doug Collins would be the most memorable name to come out of the next Olympics, the coach would have laughed or, perhaps, looked perplexed—or even asked what country Collins played for.

Here’s why: Paul Douglas Collins, the son of a county sheriff, didn’t become a starter at Benton High School in southern Illinois until his final season; after all, he stood only five foot nine as a junior. The player rarely made his presence known with his voice.

“I used to be so bashful I couldn’t hardly meet people in the face,” Collins said.

When he joined Illinois State after graduation, it wasn’t even a Division I program. Early in his tenure there, his parents got divorced, devastating him. But he persevered.

There was plenty to like about Collins, whose height soared to six foot six while a Redbird, prompting the nickname “Toothpick Slim.” Naturally tenacious, he could also shoot, becoming the third leading scorer in the nation during the 1971–72 season. But given that he played at a little-known school, being chosen to try out in Colorado Springs in the summer of 1972 was far from guaranteed.

“I had to beg to get an invitation to the Olympic Trials,” Collins recalled. “When I got my invitation, I was on cloud nine. My coach called me into his office and told me.

“To prepare for the tryouts, I spent three to four hours in the gym every day, running. We were going to Colorado Springs and I knew it was going to be in the altitude, so I was going to be in the best condition possible. I just prepared myself to go in and do the best that I could do. After a few days at the tryouts, I felt like I could play with anybody, even the cream of the crop, the players from the much bigger schools. The light went on for me that I could do it.”

Like the training camp that followed at Pearl Harbor, the disciplinarian Iba made sure tryouts in Colorado Springs—featuring constant, monotonous, grueling practices—were as miserable as possible. Said Collins in the midst of the torture, “When this is over, me and my partners are taking a van to the hills, opening up some Coors and turning on the stereo. And I ain’t never, ever comin’ back to this here Air Force Academy military fightin’ place.”

In one game at the trials, he scored 30 points, and soon after Bach kidded him, saying he better play some defense, too, for Coach Iba. Replied Collins, whose growth spurt seemed to mitigate his bashfulness, “That’s bull about my defense. . . . Iba will see. So will the Russians and all them others. We’ll win it all. Talent always prevails.”

Hovering over the free-throw line in Munich, his jersey dangling outside his shorts, Collins stared at the basket five yards away. What seemingly stood between the United States and its eighth straight gold medal was whether a one-time high school benchwarmer from a town none of his teammates could find on a map could twice toss a basketball into a braided net under excruciating tension.

Soviet forward Alexander Boloshev studied Collins.

“I hoped he was through, but when I saw his eyes, his concentrated gaze, I thought that this guy would make his two foul shots.”

Collins examined the hoop, ten feet off the ground and nearly a foot and a half in diameter. Receiving the ball from the referee, he dribbled three times and spun the ball, his free-throw regimen from his days playing in his backyard.

He tossed up the first free throw. It was good. McMillen, standing at the lane for a possible rebound on the second free throw, pumped his fists, as did Forbes; the score was knotted at 49.

“This place goes insane,” announced Gifford above the roar.

Collins walked outside the arc of the free-throw area before returning. Again, he dribbled the ball three times. He looked at the basket. As he was poised to let go of the second free throw, a horn sounded.

Despite the unexpected blare, Collins followed through unperturbed. The ball swished through the net and, for the first time all game, the U.S. led, 50–49.

“I have not seen anything grittier or guttier,” Haskins said years later. “I could not believe he swished the two free throws.”

Three seconds remained. Thanks to switching strategies— embracing a hurry-up offense and a relentless defense that forced turnovers—the United States scored 22 points in just over ten minutes to take the lead. Collins’s steal and 2 points scored were as dramatic as the events more than a quarter century later, when Michael Jordan—a man Collins coached in his first stint as an NBA head coach—did the same to win an NBA Finals for the Chicago Bulls over the Utah Jazz on the road. But while Jordan represented one city, Collins played for an entire country, which counted on the U.S. team to prove once again that freedom and a bunch of college-aged amateurs could prove superior to the Soviet state and its machinelike sports complex.

Yet the sound of the horn during Collins’s second free throw proved to be a harbinger of the most chaotic, controversial finish in the annals of the Olympics—and arguably in the history of sports.

The USA players have refused their silver medals for 50 years — and some have put in their wills that their descendants cannot accept them.

In 1972, FIBA rules on time-outs during free throws were clear: one could be called before the shooter received the ball for the second shot, but a time-out was not allowed once the player touched the ball or after he shot. Two methods could be chosen to call timeout. Coaches could push a button that sparked a red light visible to the scorer’s table or walk a few steps over to the table and signal for a time-out with one’s hands (players were not allowed to call time-outs).

According to Soviet coach Kondrashin, he had signaled for a time-out via the electronic device before Collins ever stood at the free-throw line. He assumed it would be applied before the second free throw, while not asking as much.

“The idiots, they wanted to give me the time-out before the first free throw; of course I refused,” he said. Kondrashin’s reasoning was simple; he would need to see if Collins made the first shot to figure out the proper strategy. But without letting the scorer’s table know his intention, it correctly did not give a time-out before the second free throw.

After Collins swished his second shot, Sharmukhamedov quickly inbounded, with Bulgarian referee Artenik Arabadjian waving him on. Soviet assistant coach Bashkin rushed to the scorer’s table to demand a time-out. Noticing the commotion, Brazilian referee Renato Righetto stopped play with one second left, positioning his hands into a T formation to signal an administrative time-out. The ball rested in the Soviets’ backcourt in the hands of Sergei Belov who, despite his propensity for scoring in the game, was not even in the act of shooting.

The crowd chanted “USA! USA! USA!” Iba rushed to the scorer’s table, demanding an explanation.

At that moment, a man dressed in a suit and sporting a bow tie (but foregoing his customary cigarillo) approached the scorer’s table from a seat behind the end of the Soviet bench. He lifted his thumb, index finger and middle finger to signify the number three, meaning: Three seconds should be put back on the clock. The man was the secretary-general of FIBA, which ran the Olympic basketball tournament. His name was R. William Jones.

At sixty-five, the only person in the building who had been more involved in basketball than Jones was Iba. Jones was the most powerful man in international basketball, and he was heavily responsible for getting the sport included in the Olympics for the first time in Berlin in 1936. At the same time, the FIBA kingpin was tired of watching the Americans win every Olympic game.

Coach Hank Iba — who had previously guided two gold-medal-winning teams — looks for answers amid the chaos at the scorers’ table.

Before the 1972 Olympics, in fact, Jones pushed an odd request that would boost one political bloc while harming another. He claimed that organizing a pre-Olympic basketball tournament in Munich in late June or early July would “provide the means of testing the [new] stadium and all technical facilities and equipment contained therein, as well as the personnel of the Scorer’s Table.”

In the real world, anyone suggesting that a new basketball court— similar in rectangular size and wooden materials as others around the world—needs to be tested for nearly two weeks to assess its viability would be scoffed at. The agenda was obvious: teams within a reasonable flight of Munich (read: USSR) would be able to attend for special training and games, while the United States—whose team wouldn’t even be finalized by the proposed start date—could not.

Cliff Buck, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, denounced the idea. But the pre-Olympic basketball tournament occurred anyway, without the United States, as ordered by Jones. That added to the tension already swirling around the sport of basketball. Brundage, poised to retire, declared that basketball should be eliminated from the games, since semipros were “undermining the Olympic movement.”

Since two seconds had elapsed and no time-out had been granted to the Soviets before the ball was inbounded (or after, since no FIBA rule granted retroactive time-outs), the United States argued against rewinding the clock to three seconds. After all, two seconds had been played; how could they not count? Iba had to be pushed back toward the U.S. bench by one of the referees. The scorer’s table and referees seemed unsure about the unprecedented move—and the fact that no one spoke a common language, such as English, confused matters greatly.

According to FIBA rules at the time, “The referee shall have power to make decisions on any point not specifically covered in the rules.” Putting time on the clock was well outside Jones’s purview. But considering he was the head of international basketball, Righetto, Arabadjian, and the timekeeper (who all owed their jobs to Jones) agreed to return to the three seconds that existed when Collins’s second free throw dropped through the net.

After much confusion, the teams set up for the final moments. Though the scoreboard clock had not been properly reset, instead showing fifty seconds remaining (the operator could not change the old-time digital clock from one second up to three seconds; instead, he wound it down from one minute), Ivan Edeshko received the ball from referee Arabadjian behind the baseline. The fact that he had entered the game was surprising—and against the rules. According to the FIBA rulebook, a substitute needed to report to the scorer, who would then sound the horn so both teams and the referees knew what was happening. After the chaos of the inbounds play following Collins’s free throws, no one was alerted that Edeshko would enter as a substitute (ironically enough, the one time a horn should have sounded). Further, no official time-out had been recorded where he could have entered the game after proper notification.

With McMillen guarding him closely, Edeshko bounced a pass to a nearby teammate to his left, who—as a horn again sounded unexpectedly—heaved a one-handed, eighty-foot shot that Alexander Belov tried to tip in. The ball bounced off the backboard. Three seconds had passed, and the game was over. Thanks to a remarkable comeback, the Americans had won their sixty-fourth game in a row—and their eighth straight gold medal.

Players jumped around, slapped hands, hugged and wept. Iba smiled, swept his fist through the air and was congratulated by Bach. Fans emptied out of the stands and stormed the court on the U.S. side.

“This place has gone crazy,” Gifford announced. “The United States wins it, 50–49.”

Said Henderson, “I was hugging Tom McMillen, who I couldn’t stand, so I was really happy. Someone from the stands was tapping me on my back and trying to get my shirt. He had it over my arms, and I was going to clock him. He hauled his ass away.”

Recalled McMillen, “We were all jumping up and down. It was a feeling of exultation.”

“We went through most of the game thinking we could lose, and then Doug makes those free throws and we’ve won this thing,” Davis said. “We’ve kept the streak alive—that was a sense of relief.”

“It was a great feeling. It was jubilation,” Bobby Jones said. “My job the last few minutes had been telling Jim Brewer who he was and where he was. Then I told him we won.”

Oddly, even as the celebration gathered steam, a horn kept sounding. Whistles began blowing. One of the referees approached Iba. Looking bewildered and angry, the sexagenarian walked to the scorer’s table. There stood Secretary-General Jones, his back to Iba, his hand still positioned to form the number three as he watched the scoreboard slowly change the time. A pronouncement bellowed over the loudspeakers.

“There are another three seconds less [left],” emphasized the public-address announcer with a German accent.

How could that be, when they had just played the final three seconds? Jones, with the referees’ blessing, said the inaccurate scoreboard clock meant the play was nullified. Though the scoreboard clock had been set improperly, considering only three seconds remained—an amount of time a child could count to—it seemed almost irrelevant. Referees traditionally conduct their own count when only a few seconds remain in a game, in case there is a scoreboard problem, and there was no doubt three seconds had passed and then some once the ball bounced off the backboard and bounded around the court.

One of the referees waved his right arm more than half a dozen times at American players, trying to steer them to their bench. Iba was enraged. Bach confronted Jones.

“I was up at the table trying to speak to Dr. Jones. But he kept saying ‘Three.’ And I kept saying, ‘You can’t put time on the clock.’ But his order to me was, ‘Tell Mr. Iba to put the United States team on the floor or forfeit the gold medal.’ And Coach Iba had to decide in that chaos what to do.”

According to the Games of the XXth Olympiad Munich 1972 Basketball Regulations, “Any team which without valid reason fails to appear to play a scheduled game or withdraws from the court before the end of the game, shall lose the game by forfeit.” That would seem to be a good reason why Iba and others would be worried about departing the court, especially since the United States held the lead. But who could call a forfeit? FIBA rules at the time, under the header Duties and Powers of Referee, declared, “He shall have power to forfeit a game when conditions warrant.” No one else is listed as possessing that power—including the secretary-general of FIBA, Jones.

At the same time, leaving the court seemed reasonable. After all, the team had more points at the end of the game, and thus had won it. It would take tremendous courage to hand the United States its first ever loss via forfeit merely because it refused to keep playing the final three seconds yet one more time. Haskins demanded as much. But Iba said he wasn’t going to lose the game sitting in the locker room.

Bach further pleaded the team’s case futilely at the scorer’s table, where neither the referees nor anyone in charge spoke English.

“It was the Tower of Babel,” he recalled. “Who do I talk to? Who understands what I’m saying?”

At some point Tommy Burleson—the tallest player on either team—tried to persuade Bach and Haskins that, despite his benching, he should defend Alexander Belov, who was hovering near the U.S. basket.

Iba refused.

“I was really mad—I was very upset,” Burleson said, speaking passionately more than forty-five years after Iba’s decision. “I said, ‘We’ve got to be in their face when they go up to shoot the ball.’”

Beyond inserting Burleson, another way to achieve a similar result would have been to move McMillen away from the inbounder and have him guard Alexander Belov down the court, given that McMillen stood a few inches taller than the Soviet player. Even Kondrashin, in retrospect, said the United States should have done as much. But Iba wanted McMillen on Edeshko, especially since his defense had been successful on the previous play.

Though Iba made that decision, between his arguing with the refs and trying to talk with those at the scorer’s table, he wasn’t able to orchestrate the strongest defense. In fact, Bobby Jones—who was picked for the team because of his defensive prowess and ended up as one of the greatest defenders in NBA history—wasn’t on the floor at all in the last three seconds.

The U.S. players matched up as best they could and awaited yet another inbounds play. On the Soviet side, though, Kondrashin really enjoyed two unofficial time-outs during the chaos. He had nothing to argue about at the scorers’ table, so twice he gathered his players in front of their bench and explained what he wanted from them on the final play.

Remembered Edeshko, “Coach said that I must give pass to Belov. Only one moment was possible to win—a long pass.”

Kondrashin also tried to boost their morale as they faced their only deficit of the game.

“I said that three seconds is a lot of time,” Kondrashin recalled. “Everything isn’t lost.”

Known for his passing prowess from the end of the court, Edeshko had thrown lengthy strikes to Soviet players by the far basket in games before the Olympics. He set up out of bounds, seven or eight feet deep, as McMillen bounded to the baseline. Yet unlike the previous inbound pass, McMillen then moved far away from Edeshko, ending up near the free-throw line. Why? Referee Arabadjian motioned McMillen with his left hand to move away and then made an upward movement with his left arm near the end line, which the American player interpreted to mean: stay away from the inbounder.

“The Eastern European referee kept motioning me off the line,” McMillen recalled. “The player had a lot of room to go back. Of course your arms are going to go over the line—that’s fine, as long as my feet are behind the line.

“It’s a stupid, made-up excuse that I was over the plane with my arms or couldn’t go over with them. The referee shouldn’t have been making any motions. Another problem was he didn’t speak English—I thought he would give me a technical foul if I didn’t move.”

When McMillen guarded Edeshko’s previous inbound pass, Arabadjian had made no gestures; McMillen stood right by the baseline, forcing a short pass in the backcourt.

With McMillen so far away as to be inconsequential, Edeshko moved closer to the baseline. Enjoying a clear and unimpeded view downcourt, he took one step and, with the motion of a shot putter, heaved the ball toward Alexander Belov at the other end of the court.

For the twenty-year-old Alexander Belov, the key was trying to outjump the equally tall six-foot-seven Forbes and the six-foot-three Joyce, who scurried away from Sergei Belov and began running toward the lane after Edeshko let go of the ball. Alexander Belov leaped up and clutched the ball. Forbes fell to the floor after knocking into Belov, and Joyce’s momentum carried him out of bounds.

Alexander Belov stood alone in the lane, a few feet from the basket. Achieving the Soviet Union’s first gold medal in basketball rested in his hands, only moments after he was prepared to go down in history as the nation’s biggest goat. From the field during the game, he had shot miserably, making two baskets on eleven attempts, his 37 points in a previous Olympic game a mere memory.

He looked at the basket. After one fake (perhaps out of habit, as no one was guarding him), he released a soft bank shot—and it dropped in, likely the easiest 2 points of the whole Olympics. Then the horn sounded—for the last time. USSR 51, USA 50. In the dark late night of Munich, snapped was the U.S. streak of sixty-three wins in a row, along with its Olympic hegemony in basketball, which had started hundreds of miles to the north in Berlin on a rainy court during the reign of a German madman.

This time, at long last, the game was over. But the controversy was only beginning.

To order a signed copy of Three Seconds in Munich, please send an e-mail to David at dafsweet@aol.com.