One Family’s Impact on the City

By Megan McKinney

The eldest son of John and Rachel Wrigley Winterbotham—John Humphrey Winterbotham—was introduced in our previous segment of The Winterbothams. He and his wife, the former Mahala Ann Rosecrans, of Kingston, Ohio, would be ancestors of all Chicago Winterbothams. They married in 1836 and began raising children who would grow to be notable adults. John Humphrey’s first career step was to move within Ohio to Columbus and the manufacture of agricultural tools, then on to Fort Madison, Iowa, where he and a group of friends established the Fort Madison National Bank, of which John became president.

Five Dollar bank note issued by the Fort Madison National Bank in 1871.

There was another move, this time to Michigan City, Indiana, and an assortment of successful businesses in which John Humphrey and his sons became partners within J. H. Winterbotham & Sons. Although the conglomerate was headquartered in Chicago, the patriarch remained in Michigan City and entered politics, becoming a State Senator in 1872.

Photo Credit: Duane Hall

A Civil War Monument is visible evidence of Winterbotham presence in Michigan City, Indiana.

When John Humphrey died in 1895 at 82, the children he left included John Russell Winterbotham, born in 1843, and the first Joseph Humphrey Winterbotham, in 1852. Each would establish a prominent Chicago branch of the family.

John Russell was involved in the 1883 founding of Chicago’s Continental National Bank, which through merger and name changes would develop into today’s Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust. His wife was the very social Amelia Elizabeth Morris, of Quincy, Illinois. And, although he died at 48 in 1892, Amelia lived until January 1938, continuing to operate at a high level, in Chicago and in travels elsewhere, until the age of 85.

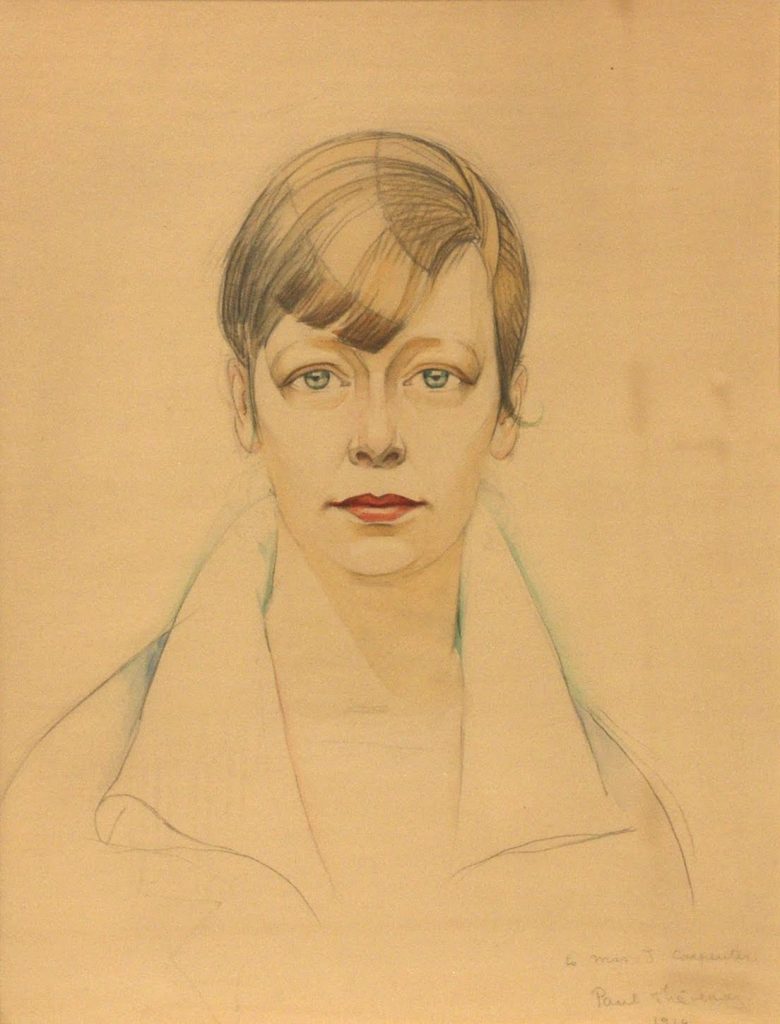

Margaret Winterbotham Poole.

John Russell and Amelia’s two daughters each made interesting marriages. Margaret wed esteemed journalist, playwright and Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Ernest Cook Poole, well-known for his coverage of Russia throughout the Revolutionary period. The wedding took place in Amelia’s house at 2215 Michigan Avenue on February 13, 1907. Ernest too was from a prominent Chicago family. His father was the successful Board of Trade commodities trader Abram Poole, his mother, the former Mary Howe and a brother was painter Abram Poole, Jr.

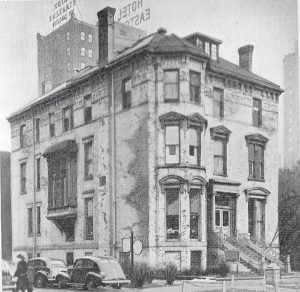

The Abram Poole house stood at the southeast corner of Michigan and Erie in the 1940’s

Katharine, the other daughter in an interesting marriage—two actually; one to an exotic royal—was born in Chicago in 1884. Her first husband was screenwriter Thompson Rodes Buchanan, with whom she was parent of Katharine Roberta Elliott and Thompson Rodes Buchanan, Jr. She then married Jehan Warliker of the Princely Clan of Seesodia of France.

Katharine and Margaret were sisters of John Russell II, born in 1889, and a graduate of the Hill School, Yale and Northwestern Law School. In 1916 he married the beautiful Doris Andrews, with whom he lived for time at 1238 North State Parkway in the glorious row of houses below.

John Russell and Doris were great joiners. She was president of both the Junior League and The Casino. In office at the latter, she was the anonymous woman who has gained great anecdotal fame in Chicago over the past half century by not answering a letter from the John Hancock Life Insurance Company offering to buy The Casino building. Other clubs to which the couple belonged were the Racquet, University, Saddle and Cycle, Onwentsia and The Tavern, of which John Russell II was for a time president.

The first Joseph Humphrey Winterbotham is best remembered for his inspired generosity to the Art Institute of Chicago; however, he was also an astonishingly active entrepreneur, who we are told “organized no fewer than 11 corporations, including cooperage manufacture, moving and transfer, and mortgage financing.” Cooperage, the making of barrels, was an important component in the dynasty’s fortunes, lasting for several generations within the parent corporation, J. H. Winterbotham & Sons.

From Ohio Joseph Humphrey moved first to Joliet, where his illustrious children were born, and then, in 1892, to Chicago. He had married an Easterner, Genevieve Baldwin, with whom he raised John Humphrey II, born in 1875; Luritia—always known as Rue—in 1876; Joseph Humphrey Jr., 1879, and Genevieve, who would marry Frank Maurer of Pasadena, California. Both boys entered J. H. Winterbotham & Sons following Yale graduation.

Joseph Humphrey, senior, traveled extensively throughout Europe for many years. Although not an avid art collector himself, he was intimately familiar with the world’s major musuems and aware of the importance of the accessibility of fine art to the cultural life of a great city. He did not have a collection to give to The Art Institute of Chicago, but he did have money.

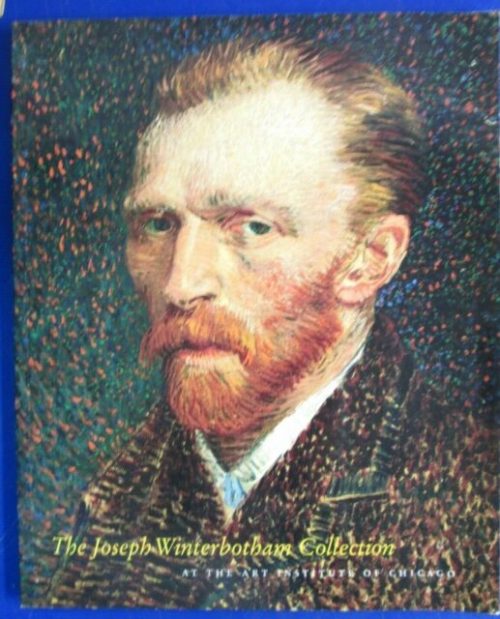

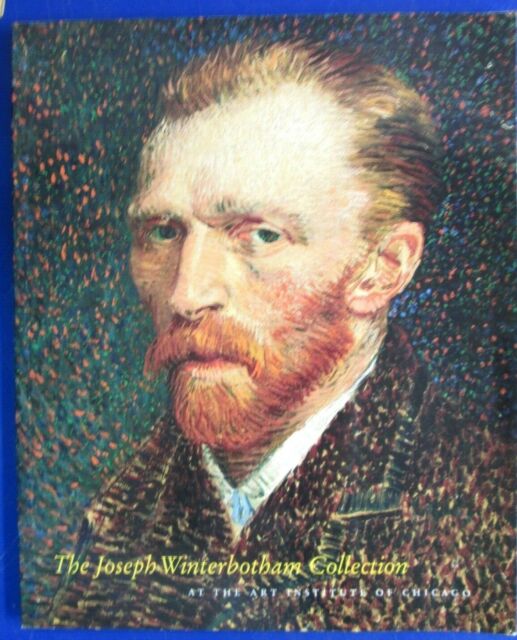

In 1921, he launched the Winterbotham Plan with a $50,000 gift to be invested and the interest used to buy paintings by European artists over a 25- to 35-year period. According to the plan, when 35 paintings had been purchased, “any work could be sold or exchanged for a work of superior quality and significance to the collection.” Thus, the consummate businessman had devised a strategy that was unique in the history of art museums, to the great benefit of the Art Institute.

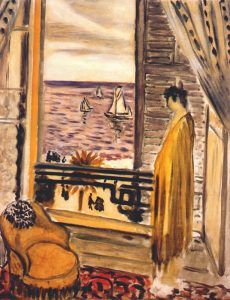

This 1919 Henri Matisse canvas, Woman Standing at the Window, was the first of the Winterbotham Plan purchases. The painting is no longer owned by the Art Institute, but it is significant in setting a tone for the Winterbotham Collection. Joseph had only specified that acquisitions be by European artists; however, ten of the first 13 were also 20th century works. At the time, some paintings from the great late 19th and 20th century collections for which the Art Institute is known had been exhibited in the museum, but the gifts had not yet been made. They would be shortly, the collection of Bertha Palmer, would be given in 1922; that of Frederic Clay Bartlett, in 1926, and the gift of the Martin A. Ryersons, in 1933.

Rue Winterbotham Carpenter

It didn’t take long for Joseph’s children to become active in shaping the collection he had endowed. After his 1925 death, two offspring, John Humphrey II and Rue, gave money to enlarge the principal to $70,000, and in 1935 Joseph Humphrey, Jr. suggested that a family member always be a participant in managing the collection. He would be the first Winterbotham to join one trustee and the director on the Winterbotham Committee, a combination that stands today. Joseph Humphrey, Jr. would be succeeded by his niece Rue Winterbotham Shaw, followed by her son, Patrick Shaw. Today Patrick Shaw’s daughter, Sophia Shaw, is the family representative on the Winterbotham Committee.

Joseph Humphrey Winterbotham, Jr.

Following Yale graduation, Joseph Winterbotham, Jr. married Eleanor Hall of Morristown, New Jersey, and they raised their one child, Louise, at 212 East Superior Street. Joseph Humphrey, Jr.’s memberships included the Chicago Club, Onwentsia and the Saddle and Cycle.

Unlike his father, this Joseph Humphrey Winterbotham was an art collector, and the Art Institute would benefit greatly from the largesse of each. At the younger Joseph’s death in April 1953, the Chicago Tribune wrote that his was “one of the largest bequests ever made” to the museum. The gift included 36 paintings and sculptures valued at—in mid-century dollars for tax purposes—$313,700, and a collection of oriental objects of art, set at $20,810. Included in the paintings was the Van Gogh self-portrait shown earlier in this segment.

Joseph Humphrey, Jr.’s total estate was $890,935; much of it left in life trust for his widow and daughter.

1301 Astor

One of the great stories of vintage Chicago real estate is the development of 1301 Astor, the stunning Art Deco cooperative at the North-East corner of Astor and Goethe. There are those who believe it was the product of another sort of “Winterbotham plan”—this one hatched by John Humphrey II, then living at 40 East Huron. In 1927, when the mere idea of hosting a cocktail party was in itself cutting edge, such an event was held in a posh Near North Side location. It was at a time when Chicagoans who could afford to do so almost invariably resided in houses—usually grand houses—either on Lake Shore Drive or elsewhere in Potter Palmer’s Gold Coast. It was generally assumed that even Palmer’s son, Potter II, and his wife, Pauline, would continue as permanent residents of the Palmer Castle itself. Until this party.

The Potter Palmer Castle.

The 1301 Astor marketing strategy was for a sleek, elegant residential building, designed by architect Philip B. Maher, to be built at the Astor-Goethe Street corner, with plans presented in advance to a gathering of prospective buyers. Architect Maher himself “recalled every floor being sold out within 24 hours of a cocktail party” and no one has ever contradicted him. Certainly not the Potter Palmers II, who moved from his parents’ Castle to a triplex in 1301 when the building was complete. Contained within the three floors of the Palmer unit was a full floor for entertaining, another for Pauline’s mother, the widowed Mrs. Herman Henry Kohlsaat, and a third, at the top of the trio, for bedrooms. The building’s remaining apartments were either duplexes or full floor simplexes. Soon living in these were some of the city’s smartest families, including that of John Humphrey II.

Next in Publisher Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasty series is Winterbothams: Rue and Rue, a segment on a pair of the most interesting women in the history of Chicago.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl