By Cheryl Anderson

“Because I was dying of boredom”

—Chanel

…..A quote from Gabrielle Chanel—her reply to Marlène Dietrich when Marlène asked her why was she going to launch herself back into the world of fashion.

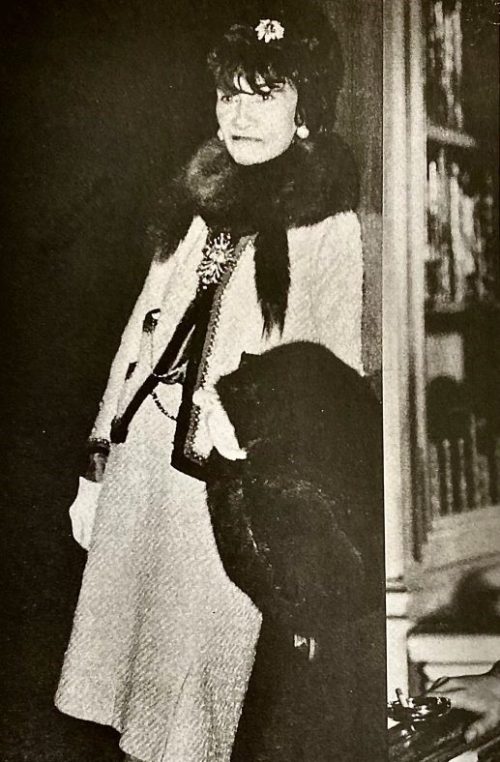

Chanel working on a model. Her first re-entry collection 1954.

The war was over, Paris was once again liberated—Chanel had narrowly escaped incarceration for her German associations during the war. So, a move to Switzerland in 1945 seemed prudent—which she made. Part of that time she lived with Hans Gunther von Dincklage, director of propaganda for the Reich. Did her friend Churchill intervene, is the most often explanation posited, or did her former lover, Westminster, intervene? There are several explanations or stories of what actually happened. Chanel was questioned in August 1944.

The Chanel “look” in Vogue March 1954 issue. Notice the tabs that buttoned onto the waistline of the A-line skirt thus keeping the blouse in place…with what has been described as a “perky bow” at the neck of the blouse. Marie-Hélène Arnaud, the face of Chanel in the 1950s, in the navy suit she modeled in the first collection. Photo Henry Clarke.

Two men arrived at the Ritz to escort Chanel. Justine Picardie states that Chanel’s maid, Germaine Domenger, with her at the time at the Ritz, says that the “interview” by the FFI was brief, that there were no powerful persons intervening and Chanel was back at the apartment within a couple of hours. Needless to say, we will never quite know the whole story—and doesn’t that make Chanel more fascinating, always and forever a mystery.

Eight years later, at the age of seventy-one, Chanel was, as she said, bored and feeling her days as a fashion designer were not over, so she picked up and moved back to Paris—her first show would be in 1954. She sold her villa La Pausa in 1953—Westminster had died and she felt it was time to let go of that part of her life.

Support from the press.

What was going on in the fashion world at the time of her decision to re-enter? Christian Dior had gained success with his new look in 1947. Other designers, all male, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Jacques Fath and Robert Piquet, were gaining recognition. Chanel believed, and was convinced, that women would once again rebel against, in her words, the “waist cinchers, padded bras, heavy skirts, and stiffened jackets”. She thought the modern woman would not go for their “illogical” style aesthetics. Women who were liberated after the war has taken an active role in society. On a mission to reinvigorate women’s fashion, once again, she would be ahead of her time and expertly launch the new modern Chanel style.

She stood at the top of her stairs during the défilé of her models. Maurice Sachs wrote: “She was a general, one of the young Generals during the [Napoleonic] Empire, seized by the will to dominate.”

Coco’s re-entry would bring to the world of fashion the iconic Chanel jacket, the quilted “it” handbag, and the two-tone slingback shoe. To this day, these three things are confirmed classics and have been for well over 60 years. She once said: “dress shabbily and they remember the dress; dress impeccably and they remember the woman.” One can always feel comfortable and confident slipping on a Chanel jacket, stepping into the two-tone shoes, and slinging the quilted bag over your shoulder— all the while feeling perfectly “turned out”.

Charles Roux: “In her little black bolero and utterly plain skirt, she seemed almost provincial. All that remained from the Chanel of yore was the obvious and undeniable severity of her taste.”

Chanel had reigned at the top of society and fashion, and now it was time to begin again. The House of Chanel had been closed since 1939 and she had lived in Switzerland since 1945. She needed to secure financing. For that, in 1953 she went to Pierre Wertheimer, her opponent in her perfume battle. He financed her comeback—in part, realizing it would be to his advantage, it would boost the sales of their fragrances. In the agreement, I read she relinquished ownership in all her businesses, but in turn, retained complete control over the designs.

Photo outside the boutique in rue Cambon 1959. Chanel trademarks in one photo…the suit, pearls, white gloves, the flat hat (reminiscent of her school days), and slingback shoes

Charles-roux describes Coco’s feelings at the time: “Chanel, whose couture house had been closed for fifteen years, felt herself afloat in the endless ‘off season. The more Dior’s star gained ascendancy, the more Chanel’s sank into obscurity.” So, Chanel decided the moment was “now” in 1953 for her to relaunch. Edmonde Charles-roux: “She lived for her work, and the passion that she brought to it was the secret of her appeal, an elixir washing over away the bitterness of exile and forced inactivity.” But one wonders, did that bitterness ever completely leave her? Paul Morand once said of Chanel: a “kind of solid appetite for vengeance that revolutions are made of.”

Karl Lagerfeld’s comment in a drawing of Chanel summing up the 1950s

She needed a new staff and new fabrics—350 workers, included fitters, cutters, pattern-makers, seamstresses were called back to work and for those that were unable to return, replacements were found. Madame Manon was charged to direct her new atelier. She had been the head of Chanel’s workroom in the 1930s. The list of fabrics she needed was long; jerseys in silk and wool, soft tweeds in wool, linens, silks laces, chiffons, and brocades—accents such as braids, buttons, and trims and lightweight silks for linings and blouses.

The Chanel suit appeared in tweed. Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld.

Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld.

She was reinvigorated getting back to work—working on the first collection for almost a year. Madame Chanel would arrive at her workroom about noon. When her assistants saw her leaving the Ritz, located across the street where she had a suite, they would dash around spraying Chanel Nº5 in the entrance of the House of Chanel, the three flights of stairs to her workroom and the salon where fittings would begin.

One of Chanel’s favorite models, Marie Hélène Arnaud, wears the suit in tweed. Photo Sante Forlano.

Days and nights before every collection, the sample garments, worn by mannequins, were presented to her from the workroom—she inspecting them one by one. This critical inspection took place in the mirror-lined salon—the same place the public would view them on opening day. Few people were allowed to be present for this, and those that were allowed were at a distance. Her working uniform was a tweed suit, but her favorite was a beige suit trimmed in red and navy.

Chanel, by Cecil Beaton 1969.

The mannequins, as well as the tailors, were silent. They knew Madame would not hear their protests of fatigue from standing for hours. Snipping stitches of an armhole with her ever-present scissors hanging around her neck on a ribbon, “using pins to reposition it point by point, all stuck in with an almost demonic thrust.”, Charles-Roux.

Chanel and her mannequin at work.

Charles-Roux: “Her face tense, Coco scrutinized the work and, spotting a suspected bulge, seized upon the defect with fingers like talons…Finally satisfied, she would sit down all but fainting with exhaustion. After taking a swallow of water, she might well say to a friend there: ‘Whatever are you looking at?’ ” Often, she was left alone as the associates were overcome with their own exhaustion. She could be humble, but oft times aggressive and sure of herself—her restless nature could step in at any time.

Photo taken on the eve of an opening. Photo Kirkland 1962

To the completed sample garments, final touches were made by her alone—necklaces, flowers, brooches, chains, and belts were available to her to choose from. Perhaps a hat was handed to her, often a variation of the straw boater she had started with, pulling it straight down until it was secure over the brow.

Chanel and Romy Schneider, whom she admired.

The fitting was over when she spoke the words: “Now…there you are…it’s not so tacky, is it? Not too bad, don’t you think? So go ahead.” The model would make her way to the podium between the Coromandel screens, pose and one last time is viewed by Madame, just to be sure. Her process ultimately leads to perfection.

Gabrielle Chanel 1964. The three pearl brooch is by Goossens. Photo Henri Cartier-Bresson

In Charles-Roux’s words, all the adjustments lead to: “The secret of her success, she knew, was in the fit: the more comfortable an outfit was to wear, the more elegant the woman who wore it.” It has been noted that Coco would at times lie down on the floor, on her back, to make sure the hem was perfect.

A tête-à-tête in her private salon with whom Chanel called “the incomparable”, Jeanne Moreau. Photo Giancarlo Botti

Charles-Roux describes the mood on February 5, 1954, on rue Cambon prior to her first postwar collection: [it] “resembled that of a courtroom in the final minutes before a verdict.” There was no music or flowers, no program was handed out, no preface at all to what they would be viewing. Chanel: “Couture is not theatre and fashion is not an art, it’s a craft.”

Elizabeth Taylor arrives in France in 1962. Chanel suit and handbag.

Friends and significant clients took their seats. They were the first to see and judge what they saw. Journalists from Italy, Germany, the United States, and England were there—the French press were seated adjacent to them. Mademoiselle herself was hidden at the top of the mirrored stairs—there she could see everything and not be seen. She sarcastically dismissed rivals as la poésie couturière—and abandoned the custom of giving names to her dresses.

Coco surrounded by her mannequins. She had been building “a stable of young women-about-town” since 1955, says Charles-Roux. She chose them for beauty and personality.

From America, there was Bettina Ballard for Vogue, Carmel Snow for Harper’s Bazaar, Sally Kirkland for Life. Paris editors came from Vogue, Elle, Paris Match, and Marie Claire and newspaper editors from, L’Oracle, Combat, Figaro and others There were buyers from B. Altman, Hattie Carnegie and Lord and Taylor from America—stores from Paris and London were represented.

Grace Kelly in Monaco at a royal palace Christmas party in 1967.

The mannequins emerged—thus began the défilé. Chanel had taught the models to glide with their neck stretched long, shoulders rolled back, hips thrust out, one hand in a pocket, if the garment had a pocket, or on the hip, and in the other hand holding a card with the style number written on it. In this first show there were jersey suits, dresses with matching coats, daytime to cocktails to evening.

Chanel posing for Vogue in 1965.

Comments about the card with a number were voiced: Jacques Cocteau, “like jockeys astride their own horses” and Paul Morand wrote, “provided with a registration number like convicts”. Even Charles-Roux wrote: “Moreover, herself agreed that after fifteen years of inactivity she had lost her touch.”

Criticism was harsh. Michel Déon, member of the French Academy, was at the opening. He published an article in Les Nouvelles littéraires: “The French press were atrocious in their vulgarity, meaness, and stupidity. They drubbed away at her age (71) assuring everyone that she had learned nothing in the fifteen years of silence. We watched the mannequins file by in icy silence”. A reason the French press was cautious, and rude, was because of her collaboration during the war—at the time the war wasn’t that long ago.

Once again, Chanel posed on the mirrored staircase–this time for Cecil Beaton in 1965. Note his reflection in the mirror.

For Chanel, the English contempt was most hurtful—Daily Mail dubbed it “a fiasco”. The American press saw it as a “break through”, saying it had a younger look—fashion and youth brought together. However, I read that some in the English press did call it a comeback the day after the first show. She began to write it off as a crushing loss. They, the press, had not yet learned the lesson that Coco Chanel was a force not to be so readily dismissed. Her comeback collection may not have been an “instant” success, but that’s when her legendary perseverance took over.

Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld.

The looks on the faces of the press and buyers showed skepticism. Her collection was nothing like the current “New Look”. As Janet Wallach puts it: “Chanel was seen as the antichrist.” There were grimaces and snickers breaking the icy silence in the room. Life magazine was courteous and American Vogue applauded. Vogue saying: “The Chanel look, as specific as [water], meant a combination of youth, comfort, jersey, pearls, of luxury hidden away.”

Chanel is hiding upstairs watching her fashion show in the reflections in the mirrors that line the spiral staircase in rue Cambon–noting the crowds reactions.

However, it’s said, the English did call it a comeback the day after the first show. She began to write it off as a crushing loss. They, the press, had not yet learned the lesson that Coco Chanel was a force not to be so readily dismissed. Her comeback collection may not have been an instant success, but that’s when her legendary perseverance took over.

Coco: “How does one become Chanel”? by Karl Lagerfeld

She would recover her “full power” in a year’s time, actually less, partly due to the popularity of the dresses, etc. in the United States. The dresses others criticized at the reopening were selling very well. Charles-Roux: “New York’s Seventh Avenue looked on with unbelieving eyes.” The buyers along Seventh Avenue called her “Coco” once again. American women couldn’t get enough of Coco’s neat little suit. Its popularity similar to that of the “little black dress”—bien sûr!

By the fall of 1954, there began to be a change from the initial attitude and by her third collection Life declared: “She is influencing everything. At 71 she is bringing in more than a style—a revolution.” The classic look was updated. Marlène Dietrich, Romy Schneider, Jeanne Moreau, and Grace Kelly were enthusiastic fans and scheduled fittings. Celebrities and the wealthy returned to Chanel in droves. American women embraced Chanel’s return and created the demand for liberating suits and jackets. Dior took notice!

Coco making one more snip.

In 1957, Neiman Marcus invited her to receive an award as the most significant designer in the past fifty years and the city of New Orleans gave her the keys to the city. Chanel sat down with The New Yorker for an interview. They called her a “formidable charmer [with] the unquenchable vitality of a twenty year old.” Nan Robertson interviewed her for the New York Times and remembers her looking “strikingly handsome” with a personality that was “snappy, feisty and forthright.”

Mannequins await and Madame continues to make the garment perfect.

Marie-Hélène Arnaud, the face of Chanel in the 1950s, was photographed by Henry Clarke for the March 1954 issue of US Vogue. Arnaud was one of Chanel’s favorite models. For the photo shoot, she wore three outfits; a red dress with a V-neck pared with ropes of pearls, a tiered seersucker evening gown, and a jersey suit, navy-blue, mid-calf, slightly padded square-shouldered cardigan jacket, with patch pockets, sleeves that unbuttoned back showing crisp white cuffs, together with a muslin blouse sporting a perky collar and bow at the neck. The blouse stayed in place with tabs that buttoned onto the waistline of the A-line skirt. The tabs hooking the shirt to the skirt brought back memories of my daughter’s school uniform, their white shirts, too, buttoned onto the pleated navy-blue skirt.

Her favorite “uniform”, beige with red and blue trim.

Bettina Ballard, of Vogue, bought the suit for herself because of its youthful elegance and insouciant impression—she remained loyal. Orders for the clothes Arnaud wore poured in. Both the editor and her readers were satisfied with the return of the classic Chanel look—they got the look in the navy-blue suit. A Chanel suit is still sought after all these years later since it first arrived in the House of Chanel.

The second collection caught the attention of Life, declaring Chanel had regained her position in the haute couture market—it had been a struggle but she prevailed. Charles-Roux: “Life agreed that the celebrated couturière had miscalculated when she made her precipitate return, but so great had been her influence already become that Chanel seemed to have initiated less a fashion than a revolution.” As Chanel simply said, when in the end, victory was hers: “A garment must be logical.” This is what she had always thought, from the very beginning of her career as a designer—simplicity. By the third season, respect and success were once again hers. Chanel became the “it” brand by maintaining a mature clientele and drew in the new generation of young women.

About the suit:

“A garment must be logical”. Chanel

A collarless cardigan jacket, trimmed in braid, with patch pockets, gold buttons with a slim graceful skirt. Jackets, straight, structured, a bit boxy, no darting, and a single seam down the center of the back. Slim sleeves set high on the shoulder, comfort and movement optimized. Chanel saying: “Elegance in a garment is the freedom of movement.”

In constructing the jacket, in her words: “The inside should match the outside.” The jackets were lined in silk. Perfection throughout! A characteristic of the jacket so that it hung properly from the shoulders was the gold colored chain sewn into the hem—perfect drop, hang and swing. The Chanel suit, as we know, became a status symbol for a whole new generation as well as a symbol of the House of Chanel—it has achieved its place in history. In 1954, the suit came in solid or tweed fabrics. To quote Chanel: [she put women] “in suits that make them feel at ease, but that still emphasize femininity.” American women embraced Chanel’s return and created the demand for liberating modern suits and jackets. Clearly, the Chanel jacket is one of fashion’s chicest and most revolutionary pieces.

Ton sur ton braid on the jacket around the neckline, down the front, around the pockets, cuffs, and hemline. This is the design we are most familiar, and the design that she favored as her “work outfit”—beige with blue and red trim. There are many photos of her with variations on the theme.

Most of the classic jackets had four patch-pockets, two breast pockets and two at the waist, jewel-like buttons that could be of a lion’s head (she was a Leo), a camellia, her favorite flower, stars, like those in her diamond collection and at La Pausa, a sheath of wheat or a double C. She created iterations of the jacket over time and Lagerfeld in some way repurposed its look in every season. Timeless! The classic design has been copied.

Villa La Pausa.

About the handbag:

“Elegance is in the lines”. Chanel

Chanel had a passion for horse racing. Always getting ideas from what she observed, the matelassé, the quilted raised surface with the diamond-patterned quilted appearance of the jackets only stable boys wore was graphic, practical and supple—thus it was this observation and recollection that gave us the Chanel handbag. It would become the “it” bag and its popularity has not waned since 1955. The lines of her design were simple.

But, it was not the first time she designed a handbag. She had introduced a handbag that was inspired by soldier’s bags with shoulder straps keeping hands-free in 1929—the convenience of a shoulder strap very much appealed to Madame—saying: “I got fed up with holding my purses in my hands and losing them so I added a strap and carried them over my shoulder.”

The updated Chanel handbag was launched in February 1955—it became the “2.55”. Convent days and love of the sporting world influenced the design. The chain strap plaited with a leather cord was inspired by the chatelaines worn by the Catholic nuns of the orphanage, the burgundy lining referenced the convent uniform. Or, perhaps the chain suggested the horse bridles and harnesses.

At the end of her life, when commenting on the fact that the Chanel handbag chain was so recognizable, said: “I know women. Give them chains. Women adore chains.” Chanel being provocative. Justine Picardie suggests: “or possibly this was as close as she could get to honesty, to an admission that she had not yet rid herself of the bonds of her past, nor stopped yearning for the links that bind a woman to a man.”

About the “two-tone” shoes:

Chanel on the shoulders of Serge Lifar around 1937. Notice the “sandals” with the black toe she is wearing. These shoes influenced her “two-tone” pumps.

“They are the height of elegance”. Chanel

The Chanel pump/slingback first appeared in 1957. Where did the idea for a “two-toned” shoe for women come from, you might ask? Chanel was always observing, analyzing and visually dissecting the aesthetics of clothing she saw. One observation was that of the black-toed shoes the sailors wore on the Duke of Westminster’s yacht, the Flying Cloud—natural fabric and black leather points.

The other shoes whose aesthetics she thought practical were the “sandals” worn by her dear friend Serge Lifar, dancer and choreographer—his were beige canvas with thick soles and black leather tips, commonly worn by participants for sporting activities and camouflaged stains that may occur. She was amused by the way Lifar nonchalantly slung them over his shoulder. Chanel can be seen wearing these sports shoes in the photo of her on the shoulders of Lifar in 1937.

Chanel took her ideas to Raymond Massaro and his father, both shoemakers— it turns out, they were drawn to the Chanel brand. They conceived the asymmetrical sandal—the shoe provided freedom for running, dancing, jumping into the city, as one author said, with comfort.

To Chanel Raymond Massaro said: “the worst thing that can happen is for a woman to be angry with her shoemaker during a night out.”

“We leave in the morning with a beige and black, we lunch with beige and black, we go to a cocktail party with the beige and black. We are dressed from morning to night.”, Chanel words when presenting the shoes.

No more buckles, as the slingback with an elastic strap supports the heel! The blacktip, slightly squared, shortens the foot, and the beige melts into the ensemble, elongating the leg. The tip in black protects the pump from weather and normal wear, the 5cm high heel was comfortable— then and now, there remains an A-list of fans.

The design of the modern two-tone shoe is considered one of the greatest technical innovations in the history of shoemaking. Before then women only had monochrome and often had dye shoes to match the outfit. The press tagged them the new “Cinderella slipper”. They have not declined in popularity. The same beige leather had tipped in navy, brown, or gold. “With four pairs of shoes I can travel the world.”, Chanel.

About Robert Goossens’ jewelry:

“They are magnificent—if people ask where they came from we will say the excavations at rue Cambon!” Chanel

…this her reply when Robert Goossens told her his designs were influenced by Barbarian, Visigoth, and Etruscan jewelry.

Robert Goossens, the goldsmith and French jeweler, was to whom she turned for the new line of jewelry she sought to have produced. They met in 1953. Like Chanel, he liked to mix faux with semi-precious stones in these designs.

A piece he is best known for, is a gold brooch with three very large pearls and a diamond— apiece Chanel wore and was replicated in her new collection. It’s visible in one of the pictures featured with this article. Chanel also commissioned furniture, chandeliers, and mirrors from Goossens for her Paris apartment at 31 rue Cambon.

Designers seek to design something that is forever recognizable as being their design beyond their lifetime—few achieve such a triumph. Chanel achieved it with a jacket, a handbag, and a two-tone shoe—and lest we forget, Chanel Nº5 perfum.

“I don’t like people talking about the Chanel fashion. Chanel—above all else, is a style. Fashion, you see, goes out of fashion. Style never.”

À bientôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson

The Allure of Chanel, by Paul Morand, published by Pushkin Press 2017 Translated from the French by Euan Cameron

The Golden Riviera, by Roderick Cameron, published by Editions Limited

Diana Vreeland -The Eye Has To Travel, by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, published by Abrams, New York

French Riviera – Living Well Was the Best Revenge, by Xavier Girard, published by Assouline.