New Book Charts the Career of Pioneer Race-Car Driver Fred Wacker Jr.

By David A. F. Sweet

Long before races — such as today’s Daytona 500 — became televised spectacles featuring professional drivers whose livelihoods are tied to their steering wheels, amateur sportsmen competed against each other in the United States and Europe, laying the foundation for today’s accomplishments on asphalt.

Fred Wacker Jr. was one of those pioneers. He raced in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, participated in the inaugural General Peron Argentine Grand Prix on the streets of Buenos Aires and compiled more than a half dozen first-place finishes in his career. The new book Fred Wacker, Gentleman Racer, 175 pages and published by Henschel HAUS Publishing in Milwaukee, vividly describes his exploits and is graced with dozens of photos of Fred dashing around in the fastest cars of the day. Consider it an authoritative look: after all, his son Fred Wacker III is a co-author.

Fred Wacker Jr.’s new MG, purchased in 1948, was not a hit with his father — until he looked under the hood.

Born in Chicago during World War I, as a boy Fred Jr. attended the opening of Wacker Drive, the city’s iconic roadway named after his grandfather Charles. With his father he watched the Indianapolis 500 in 1932, which likely spurred his love of racing. He later graduated from Hotchkiss and Yale and served in the South Pacific during World War II.

Though Fred Jr. was passionate about cars and motorcycles, his father did not embrace his devotion, prompting Fred Jr. to keep his motorcycle at a friend’s house in secret. When his parents bought him a clunky car as a gift, Fred Jr. traded it in and returned home with a black, two-seat 1948 MG with the number 8 painted on the side.

“My dad was rather upset when he saw my little MG for the first time,” says Fred Jr. in the book, as his father worried his son would get killed in the tiny car. “But after a closer look at the mechanicals under the bonnet, his concerns lessened and he came to like it.”

In 1949, Fred Jr. launched his racing career, entering the MG at the second Watkins Glen Grand Prix race in New York, where he finished ninth. By the time of the 1950 event, he had upgraded to a faster car — a Cadillac-powered Allard roadster, which became known as the 8-Ball. He captured third.

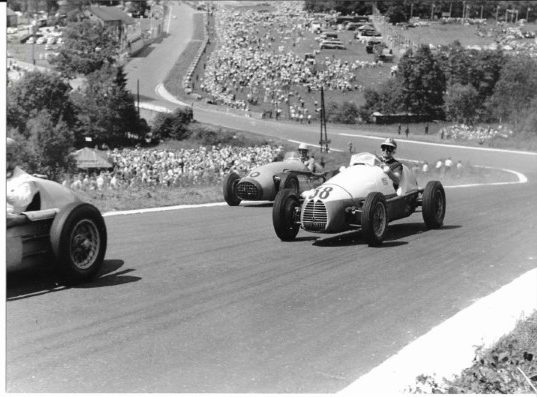

This photo graces the cover of Fred Wacker, Gentleman Racer.

The next year, Fred Jr. joined the team of famous racer and car builder Briggs Cunningham for the 24 Hours of Le Mans in France. Driving as fast as 180 mph and negotiating complicated turns through small villages, Fred Jr. and his driving partner George Rand fared well until Rand – whose headlights weren’t working in the dark — crashed on lap 77.

Racing at Le Mans again in 1953, Fred Jr. drove with Phil Hill, then a rookie who became one of the best drivers of his generation, winning Le Mans three times. Unfortunately, as the clutch, brakes and engine failed, the duo were forced to stop after 115 laps.

Back in the United States, Fred Jr. was focused on improving the safety of races. An event in 1952 had shaken him badly. During the Watkins Glen race – where his fastest-qualifying time earned him the pole position — his left fender struck a 7-year-old boy, killing him. Accidents like that prompted racing to leave public streets, where the crowds stood only feet from the speeding vehicles, for tracks which afforded spectators protection.

Fred Jr. was a chief proponent of this switch. After Watkins Glen, the racer – then the president of the Sports Car Club of America – worked with Curtis LeMay, commander of the Strategic Air Command, to craft a solution to improve safety. They ended up scheduling races at air bases across the country.

Fred (right) competes in the 1953 Grand Prix de Belgique in a Amedee Gordini car.

Closer to home, Fred Jr. formed the Chicago Region of the Sports Car Club of America. He and a friend, Jim Kimberly of Kimberly-Clark fame, flew a small plane over southeastern Wisconsin to scout land for a racetrack. The duo chose Elkhart Lake. They organized three open-road races from 1950-52, with Kimberly winning the inaugural event. The number of cars entered soared by the third year – 238 in 1952 versus 33 in the first race – and about 100,000 spectators watched. In 2006, the original country-road course joined Watkins Glen on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fred Jr. suffered one serious accident in his racing career. During the Grand Prix de Suisse in 1953, a Formula One race, he had little time to prepare and arrived late. Having never driven the course, he was thrown from the car as it flipped and suffered broken ribs and a skull fracture among other injuries. For several weeks he was ensconced in a Swiss hospital.

Despite the crash, Fred Jr. was not demurred. The following year he raced in the Italian Grand Prix. But in 1956, he retired. As racing transitioned from a gentleman’s occupation to a full-time pursuit, Fred Jr. decided it was more important to have a steady job in the Chicago area.

“His racing career was more of a hobby and a passion. He was a sportsman,” explained Fred III. His gracious, humble father was also an accomplished musician who loved jazz and ran two bands: Freddie Wacker and the Windy City Seven and later, the Fred Wacker Big Band.

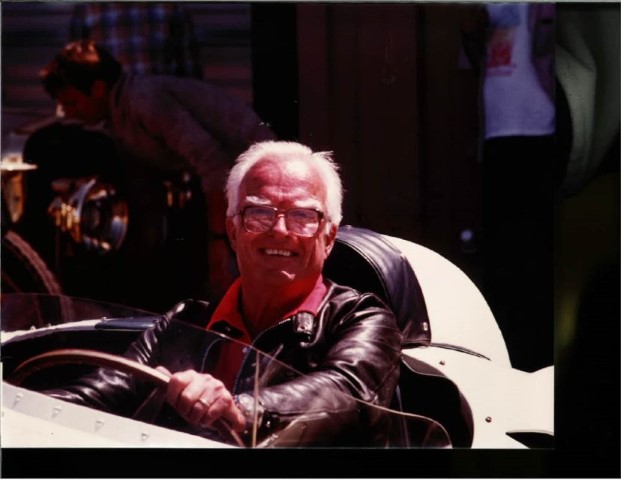

In 1981, Fred enjoyed getting together with old pals during a Briggs Cunningham driver-and-crew reunion in California.

How did the book come to be? While cleaning the basement of his parents’ house a number of years ago, Fred III came upon a few aging boxes. Upon opening them, he found race programs, trophies, articles from Life magazine and more. They were his father’s mementos from a race-car career.

“I start digging through it, and it was a treasure trove,” said Fred III, who grew up in Lake Bluff at a house filled with kids riding mini bikes outdoors and who crossed the United States on a 1913 Indian motorcycle five years ago.

What to do with all of this memorabilia? Through a friend, Fred III got in touch with Robert Birmingham, who had written a number of racing books, including Augie Pabst Behind the Wheel about the great-great grandson of the beer entrepreneur. Pabst was one of the best sports-car racers of his day.

“After I introduced myself to Bob, he said, ‘I watched your Dad race when I was a kid. He was a legend,’ recalled Fred III about the opening conversation. “I told him about the idea of a book. He said, ‘Let’s start tomorrow. I’m 83.’”

The book is a tremendous tribute to Fred Jr., who died in 1998 just short of his 80th birthday. For Fred III, who was extremely close with his father and attended dozens of Indianapolis 500s with him, this labor of love is a perfect gift for future generations to remember a beloved gentleman racer.

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.