BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

If Agnes Northrop could see it now: throngs of visitors ascending the Art Institute of Chicago’s grand staircase, coming face to face with the Hartwell Memorial Window. What would she be remembering of her fellow Tiffany Girls?

The stained glass artist for Tiffany Studios was at the height of her power in 1917 when she designed the dazzling Hartwell window, dramatically backlit to mimic sunlight flooding through, creating a kaleidoscope of color. As head of a group called “The Tiffany Girls,” she created some of Tiffany’s most memorable windows and was the first at the preeminent studio to execute landscapes and gardens in stained glass. She was a true virtuoso in what was referred to at the time as painting in glass.

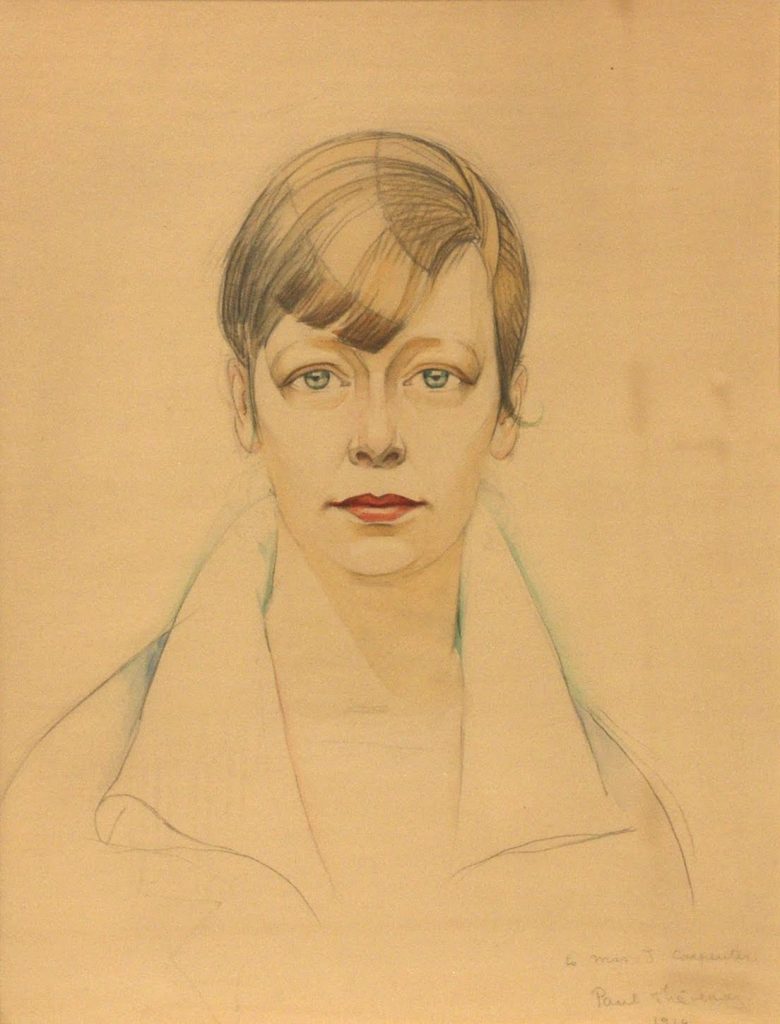

Agnes Northrop.

Tiffany Girls.

Sarah Kelly Oeler, the Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of Arts of the Americas who has worked for the past four years to bring Northrop’s window to the Art Institute, shares a little of the artist’s history: “For five decades Northrop worked closely with Louis Comfort Tiffany and as the years passed, she was unfortunately overshadowed by his work. She was actually Tiffany Studios foremost landscape window artist.”

She continues, “Northrop early on directed the efforts of the Women’s Department at the Tiffany Studios, a cadre of talented women who were crucial to the studio’s creative and technical operations. Women selected and cut the glass. Men worked on the lead parts surrounding the glass. In the time just before World War I, many women were beginning to attend art schools and Tiffany hired a good number to work in their women’s department. You could not be married if you were a woman employed there, men could be married. Northrup worked there for five decades and never married.”

Mary Hartwell, a wealthy Rhode Island widow, commissioned the eponymous window for a new building to be constructed by the Central Baptist Church in Providence. Her husband, Frederick, an industrialist who died in 1911, had been an active deacon there. The church is now the Community Church of Providence and is located not far from Brown University.

Hartwell Memorial Window.

“It was a very unique commission,” Oehler explains. “There are hundreds of landscapes showing Biblical scenes, but this scale and subject is extremely rare for an ecclesiastical site. It depicts Mount Chocorua in the White Mountains of New Hampshire where Frederick grew up. A landscape was a very unique commission: most Tiffany windows executed for churches, such as the magnificent ones at the Second Presbyterian Church in Chicago, had Biblical themes.”

The Hartwell Memorial Window provides a vision of tranquility for anyone experiencing the rush of “open sesame” Chicago. Acquired by the Art Institute 100 years after its creation and just recently installed, it greets visitors anxious to make up for lost time during the pandemic with a breath of fresh New Hampshire air and the luminosity that only the Tiffany Studios could achieve.

“We are hearing that visitors find it very emotional, moving, and gratifying, perhaps finding a feeling of spirituality through a sense of place. Although it is certainly idealized, it is a rare landscape executed for a church and monumental in scale. When it hung in the church in Providence, it was 25 feet above the ground. Now you can closely inspect it,” Oehler said.

Center detail.

Climbing the Women’s Board staircase, I followed Oehler’s instructions to first stand opposite the window and then enjoy the rare opportunity to examine the window, once completely out of reach, and all of its glistening overlaid colors and varieties of glass. Composed of 48 panels, the church window measures 26 feet by 18 feet. The majestic scene captures the transitory beauty of nature—the sun setting over a mountain, flowing water, and dappled light dancing through the trees—in an intricate arrangement of vibrantly colored glass.

The window represents innovation in painting in glass at its finest. There are at least five different kinds of glass, including foliage glass, which is embedded with confetti-like shards and flashed glass, and clear glass overlaid with intensely colored glass, built up anywhere from two to five layers thick.

Window detail.

More detail.

“We were approached in 2017 to see if we had any interest in purchasing the window completed 100 years ago. The church recognized how special it is and wanted it to be safeguarded as well as seen by many more people. Many of church windows have been disassembled or destroyed. They wanted it maintained and appreciated,” Oehler shares. “Previously, it had not been on anyone’s radar. I knew from the get-go that this would be an extraordinary treasure. I found every inch to be dazzling and captivating.”

De-installing, conserving, and reinstalling a stained glass window this intricate and monumental called for an unprecedented plan to maintain the historic integrity of the Tiffany Studios craftsmanship while showcasing the range of effects achieved in the glass. Among the key donors to its purchase are the Antiquarian Society, the Chauncey and Marion Deering McCormick Family Foundation, and Ann and Samuel M. Mencoff.

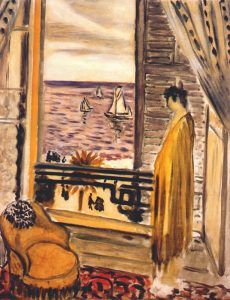

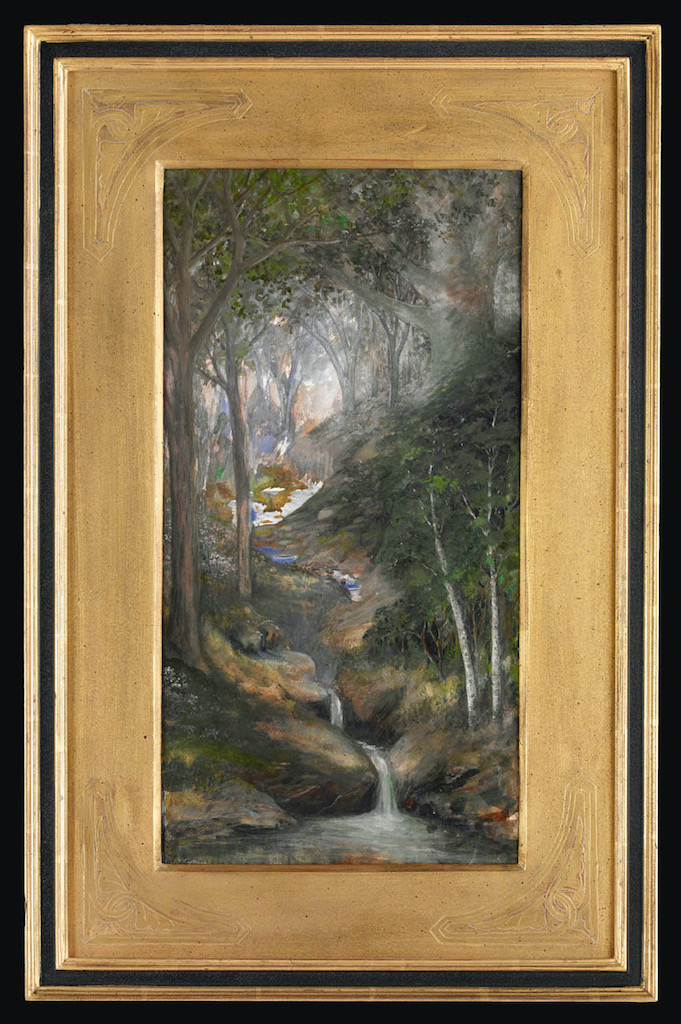

Anna Musci, the newly appointed executive director of the Driehaus Museum, which also includes Northrop works as part of its collection, tells us more: “Before there was a window, there was a sketch, a study, and a full-scale cartoon. ‘Landscape’ is a study for what would likely have become a Tiffany stained-glass landscape window and was created by Agnes Northrop, who ranked top among the female Tiffany artists. Already an accomplished artist in constant pursuit of capturing nature in her photographs and paintings, Northrop honed her skills as a stained-glass window designer working for Louis Comfort Tiffany as early as 1884 and remained with Tiffany Studios until it closed in 1932.”

Landscape, 1890-1925, Agnes Northrop (American, 1857-1953). Gouache and oil on board. Collection of the Richard H. Driehaus Museum, Chicago. Photograph by John Faier.

“In this study, a stream flowing through the forest hinted of the ‘River of Life,’ a popular motif in Tiffany Studios ecclesiastical commissions, which were featured in the Museum’s 2019 exhibition Eternal Light: The Sacred Stained-Glass Windows of Louis Comfort Tiffany,” she adds.

The Driehaus Museum has Fourth of July program kicking off the first of the month and running until the month’s end that brings a little hint of this piece to the forefront. As part of their Live From the Drawing Room series, they’ll discuss a new form of classical music in America, Copland, from the early 20th century that was influenced by the eclectic and uniquely American art of the late 19th century: Tiffany.

Some viewers of this very special Tiffany creation have made the connection between it and Psalm 121, which begins: “I lift up my eyes to the mountains—where does my help come from? My help comes from the Lord, the Maker of heaven and earth.” No matter where your beliefs lie, looking up at this magnificent window, with nature rendered in all its glorious colors, is a truly divine experience.

To learn more about the Hartwell window at the Art Institute of Chicago, visit artic.edu. For more on the upcoming Driehaus programming, click here.

Full image credit for all Hartwell window photos, provided by The Art Institute of Chicago:

Design attributed to Agnes F. Northrop (American, 1857–1953)

Tiffany Studios (American, 1902–32)

Corona, New York

Hartwell Memorial Window

1917

Leaded glass; 798.7 × 554.7 × 42.5 cm (314 7/16 × 218 3/8 × 16 3/4 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, purchased with funds provided by the Antiquarian Society, the Chauncey and Marion Deering McCormick Family Foundation, and Ann and Samuel M. Mencoff; through prior gift of the George F. Harding Collection; Roger and J. Peter McCormick Endowment Fund; American Art Sales Proceeds, Discretionary, and Purchase funds; Jane and Morris Weeden and Mary Swissler Oldberg funds; purchased with funds provided by the Davee Foundation, Pamela R. Conant in memory of Louis John Conant, Stephanie Field Harris, the Komarek-Hyde-Soskin Foundation, and Jane Woldenberg; gifts in memory of John H. Bryan, Jr.; Wesley M. Dixon, Jr. Endowment Fund; through prior gift of the Friends of American Art Collection and Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson; purchased with funds provided by Jamee J. and Marshall Field, Roxelyn and Richard Pepper, and an anonymous donor; Goodman Endowment Fund; purchased with funds provided by Abbie Helene Roth in memory of Sandra Gladstone Roth, Henry and Gilda Buchbinder Family in memory of John H. Bryan, Jr., Suzanne Hammond and Richard Leftwich, Maureen Tokar in memory of Edward Tokar, Bonnie and Frank X. Henke, III, Erica C. Meyer, Joseph P. Gromacki in memory of John H. Bryan, Jr., Louise Ingersoll Tausché, Mrs. Robert O. Levitt, Christopher and Sara Pfaff, Charles L. and Patricia A. Swisher, Abby and Don Funk, Kim and Andy Stephens, and Dorothy J. Vance; B. F. Ferguson Fund; Jay W. McGreevy, Dr. Julian Archie, Mr. and Mrs. John W. Puth, and Kate S. Buckingham endowment funds, 2018.121.