By Megan McKinney

Inside Sam Insull’s magnificent Benjamin Marshall villa.

During his deprived upbringing in a tiny rented London dairy, Sam Insull’s most predominant characteristic was his energy. It was a trait that would remain with him throughout his life.

Samuel and Emma Insull in about 1866, with their children at the time, Sammy, Emma, Queenie and Joseph.

When, as a young man, he decided to learn shorthand, Insull approached the project—as he did everything—with a vitality that was nearly “demonic.” He became a brilliant stenographer, leading to a rapid and seemingly presaged progression of events that would transform his life.

The young Sam Insull.

The sequence began in November 1878, when the 19-year-old picked up a copy of Scribner’s Monthly and became fascinated with an article on 31-year-old Thomas Alva Edison. Almost immediately, the American inventor became his idol. Less than three months later, Insull was fired from his job as chief shorthand clerk for an auction house in favor of the son of an important client. Though devastated, he straightaway answered a classified ad in the morning Times; it was for a secretarial position that seemed perfect for him.

It was perfect—far more so than he could possibly imagine. The ad, although Insull didn’t know it at the time, had been placed by the London representative of Thomas Edison.

The youngish Thomas Edison.

In 1881, Edison, who was struck with Insull’s weekly reports, sent for him to come to America, where he became Edison’s personal secretary in the inventor’s new headquarters at 65 5th Ave., for which he had just left Menlo Park.

Off and on for the next 11 years, Insull woke Edison in the morning, bought his clothes, wrote his letters, made him stop working long enough to eat meals and reminded him when he had forgotten to wear a necktie. Meanwhile, he became thoroughly acquainted with the new phenomenon of electricity and the technical side of the emerging light and power business.

In time, Insull moved on to Schenectady, New York, where he participated in establishing the manufacturing arm of the precursor of General Electric. In 1892, he wrote to the capitalists controlling the fledgling Chicago Edison Co. suggesting himself as president. He was successful in his quest, and, within five years, he had incorporated another Chicago electric company.

In 1907, he merged the two, creating Commonwealth Edison Co., the monopoly that delivered Chicago’s electricity. What he had done with electricity, he repeated with gas, and, in 1913, became Chairman of the Board of the Peoples Gas, Light and Coke Co.

During the 1920s, Commonwealth Edison Co. was reaching half a million people and generating annual revenues of almost $40 million. One of Insull’s companies, the immense Middle West Utilities Company, delivered one-eighth of the country’s electric power to 32 states and parts of Canada.

Sam Insull.

Insull was a small, thickset man, with a mustache, dark eyes, silvering hair and an Englishman’s ruddy completion. He continued to approach everything with great energy and displayed an almost autocratic self-assurance, but was soft-spoken—and always half-smiling—while issuing decisive orders in the low-voiced English accent he never lost.

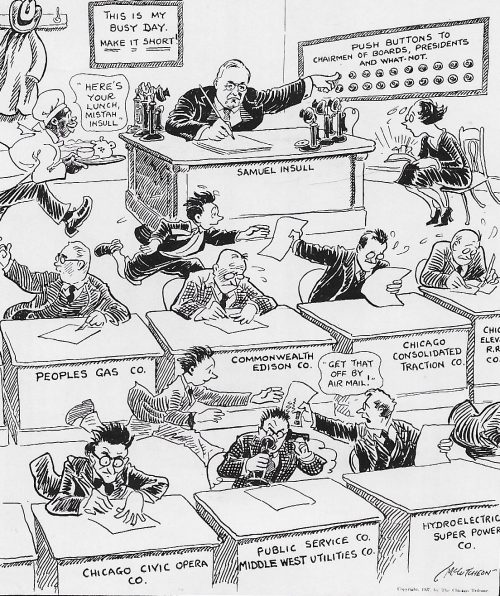

The complexities of the burgeoning Insull Empire would not escape the keen eye of the sophisticated Chicago Tribune political cartoonist John T. McCutcheon.

His routine, as the years went on, began at 7:10 every morning, when he arrived at his mahogany-paneled Commonwealth Edison office. Because of an Englishman’s dislike for steam heat, he had a log fire to keep him warm. At 12:30 p.m. sharp, he would lunch with a friend or business associate at the Chicago Club. And afterwards, he might visit one of his other offices in the Peoples Gas Building or the Chicago Civic Opera House.

Gladys Wallis.

In 1898, when Insull was 36, he saw actress Gladys Wallis in a touring company production of The Squire of Dames, with John Drew, Maude Adams and Ethel Barrymore, and instantly became her “starstruck admirer.” When they later met at a dinner party, he began an intense pursuit for her attentions, which resulted in their marriage two years later.

More of Gladys Wallis.

Wallis was known as a “pocket Venus”; at under five feet and weighing less than 90 pounds, she appeared to be fragile, but was not. Insull soon learned that she was as rigid as she was pretty. Because of her profession as an actress, being viewed as respectable had been important to her. However, as it turned out, so-called “respectability” was not merely her image but a central part of her character. Wallis was anti-alcohol, which was fine with Insull, who was from a temperance background, but she was also frigid, which was not. The latter would be a prime factor in the turbulent marriage and presumably the eventual intrigue that would develop.

And still more of Gladys.

She was also demanding and chronically dissatisfied, never letting Insull forget she had given up her career to marry him. Actually, she wasn’t that unhappy to have left the stage, at least initially. She soon became a grand lady, enjoying the world of charitable fund-raising and social functions, as well as the beautiful housing, expensive gowns and luxurious jewels Insull was increasingly able to provide. However, her difficult personality did not make her popular with the other ladies in Chicago’s social world.

Although Insull was well liked by his immediate associates, on the whole they were an unpopular couple in Chicago society, which considered her frivolous and him boorish and underbred. . .

Coming Up: Megan McKinney’s Insull series will feature Sam Insull’s Turbulent Home Life . . . and Escalating Empire next week in Classic Chicago.

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl