BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Distinguished collectors have rightly given Rhonda Brown’s powerful canvasses portraying African American women in bold Expressionist colors places of honor in their homes in Chicago and across the country. We are excited to share her family legacy with you and more about her work and artistic process.

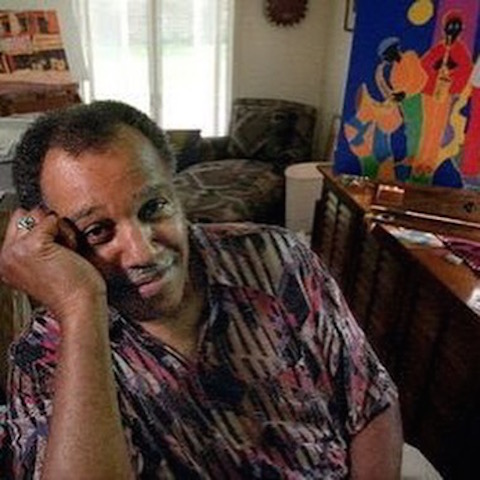

Rhonda Brown. Photo by Sonya Martin Photography.

We asked one of our favorite and most discerning people, Jillisa Brittan, what drew her to Brown’s work: “I am fortunate to have three of Rhonda Brown’s paintings. I purchased the first one over fifteen years ago and commissioned the most recent one in spring 2020 as a gift for my husband Jeffrey’s decade-changing birthday. In visiting the Art Center Highland Park where Rhonda’s work was exhibited in late summer 2019, Jeffrey fell in love with her ‘Royals’ series: beautiful, strong, contemporary Black women seated on their thrones. So, I asked Rhonda if she would paint a ‘Royal’ for Jeffrey’s birthday.”

“I find Rhonda’s work to be visually beautiful and evocative, as well as multilayered in its allusions to contemporary culture and the artists whose work has inspired her,” Brittan adds.

Royal I, 2019.

Royal II. Acrylic on canvas, 2020.

Georgia Peach, 2007. Collection of Jillisa Brittan and Jeffrey Smith.

Brown shares, “I have a master’s degree in art history from University of Wisconsin and double majored in painting and drawing and art history at Ohio State University. Over the years, I have seen a ton of art. Taking the time to fully immerse yourself with artwork, I believe, makes you better. Like my father always did, I enjoy paging through retrospective and exhibition catalogues—it’s part of my practice. Right now I am looking at Kerry James Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and many emerging contemporary Black photographers.”

“From the very beginning, I have been preoccupied by the way in which we, Black women, carry and construct the weight of the world: how we wear it, what we do with it, and what it becomes,” she continues. “You will experience that heaviness in my work. I use expressive line, shape, and color to exaggerate my figures and backgrounds. My goal is to invite the viewer into a dialogue and to evoke a response to the painting.”

Samori’s Mother. Acrylic on canvas, 2020.

Stacey Yvonne. Acrylic on canvas, 2020.

Command. Acrylic on canvas, 2011.

Brown herself is grounded in the tradition of her father, Malcolm Brown, a noted painter and arts educator who passed away from Alzheimer’s this past October. He was the first Black member of the prestigious American Watercolor Society and in 1980, her mom and dad founded the Malcolm Brown Gallery in Shaker Heights, Ohio. The gallery was the first for-profit, Black-owned fine art gallery in the country and featured her dad’s work alongside Black artists of international prominence such as Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, John Biggers, Hughie Lee Smith, Fred Jones, Moe Brooker, Selma Burke, and many more. Her parents introduced the region to significant artists who, at the time, had rarely been exhibited in art museums or galleries in the heart of the United States.

The artist’s late father, Malcolm Brown.

Malcolm Brown as a young boy with his twin brother (in peacoats), 1937/38.

Malcolm Brown, Zelma Watson George, Elizabeth Catlett, and Ernestine Brown.

In a 2011 ideastream interview, Rhonda’s mother, who was recognized as an outstanding businesswoman in Ohio, said the plan was to inject some diversity into a largely white art scene, saying, “Our focus was to expand awareness, to widen the prism for viewing, appreciating and collecting art by African American artists.”

Although the pandemic prevented us from visiting Brown’s studio and home, situated in a Jeanne Gang building in Hyde Park, our conversation was capped by a YouTube video of the artist at work. Rhonda paints with intention. Her work feels organic. It seems to just flow, prompting us to ask, “Do you ever get the artist’s version of writer’s block?”

“There have been moments, as with all artists, where you hit a snag and have to stop working all together,” she responds. “Juggling children, work, and life in general can be draining. As a result, you can lose your creativity while working through a composition. In those moments, I take a number of photographs to see the canvas in new ways. But for me, after I pause and start again, the work is always stronger. Seeing the work through a different lens provides all I need to get back on task.”

Earth Angel Ms. Gwen, 2020. Collection of Dede and Laird Koldyke.

Bathers, 2019. Collection of Denise and Gary Gardner.

Chapeau de Paques. Gouache on paper. Collection of Barbara Bluhm and Don Kaul.

She holds a dual role at the City Colleges of Chicago as Vice Chancellor for Institutional Advancement and President of the City Colleges of Chicago Foundation. Brown creates in the evenings and weekends at her in home studio. Her youngest son, Isaac is a sophomore at Mount Carmel High School and her oldest son, Avery, graduated from Amherst College this past spring and is starting his career with an investment management firm in New York City.

The Son. Gouache on paper, 2020.

There are many layers to Brown’s work. In 2007 she created a series of paintings based on Edouard Manet’s painting, previously called Olympia: “The research that prompted the name change of Olympia didn’t exist when I made the work. But I wondered about the woman with the flowers. There had been so few paintings with Black women portrayed during that period of time.”

The Musée d’Orsay changed the name of the painting to Laure in honor of the model and others giving agency to their existence. “How we are portrayed and perceived is crucial to being seen as women and as humans,” says Brown.

Laure by Edouard Manet, 1863.

Don’t Touch my Crown is a piece that emerged out of a discussion about the Crown Act, a piece of legislation prohibiting discrimination based on hair style or texture. “Enough is enough,” Brown says, sharing her experience back in February during a trip to Ghana. “I saw every shape, shade, and hairstyle imaginable. There is nothing more important for us as Black Americans than to see, hear, and experience what our ancestors endured. At the same time, it is critical to understand our vitality, beauty, brilliance is connected to the origin of civilization. Can you imagine someone trying to legislate what hairstyle you can or cannot wear? Think about it—it is our right to wear hairstyles free from discrimination.”

Don’t Touch My Crown. Acrylic on canvas, 2020.

Untitled. Acrylic on canvas, 2010. Collection of Leslie Bluhm and David Helfand.

We have seen Rhonda’s work in situ and it holds its own. Her work is amazing and she is most definitely one to watch. To learn more, visit rkbfinenart.com, follow her Instagram page @rhondabrownfineart, or set up a virtual studio visit via Zoom by emailing rhonda@rkbfineart.com.