BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

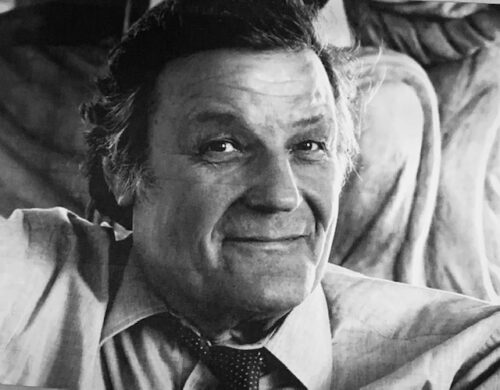

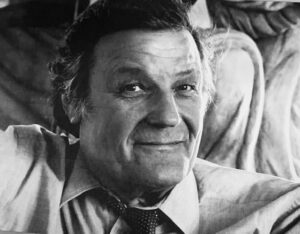

Whether headlining Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball or sharing the stage with the Supremes for a deb party at a Lake Forest country club, in the six decades that he has played the most exclusive dance floors in the world Peter Duchin has always lived up to his theme song, “Make Someone Happy.”

Bandleader and epitome of elegance, Duchin did it again last Friday, an evening that began with a call from one of his favorite friends, Abra Prentice Wilkin (who regretted not being there but wished him good luck). He imbued the room with joy and shared fond memories with the elegant crowd, revealing that his most memorable party wasn’t Capote’s or even a night at the White House—it happened right here in Chicago: “I was asked to bring my 10-piece orchestra to the Palmer House by the hostess who shared no other details,” Duchin recalled. “When we arrived, we found just one table set for two in the center of the room. We played all night just for the couple celebrating their 60th anniversary. She told me that it was the happiest night of their lives.”

Having entertained presidents, kings, and queens, and serving as Audrey Hepburn’s chosen date for the Paris Opera Ball, no one knows café society better. He has played at over 5000 events around the world, from civil rights organizations to grand galas, his dazzling smile enticing thousands over the years to the dance floor.

Early on in his career, Duchin appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, the longest-running and most popular variety show ever.

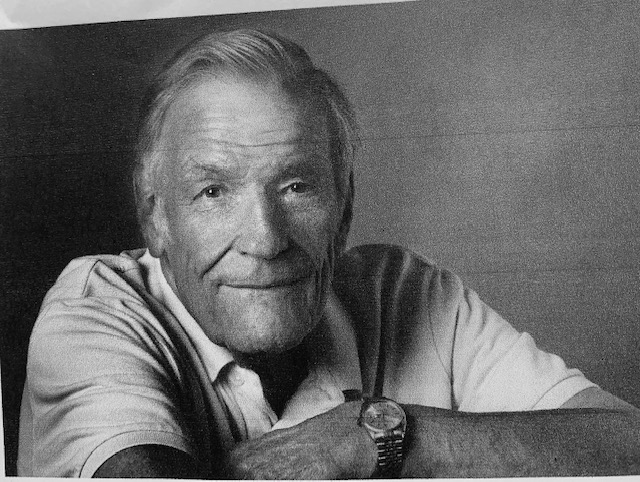

In town to publicize his second book, Face the Music, the legendary Duchin told Classic Chicago how he made use of his signature song to make another group of people happy: those who could not get up and dance. Duchin is a legend twice over, doing the unimaginable, not only recovering from a 2013 stroke but from an astounding 47 days on a ventilator with COVID beginning in March of 2020. He used his time in recovery to encourage fellow patients undergoing physical therapy to make themselves happy no matter what.

“That is why I wrote the book, to tell people to not give up,” he shared. “After both recoveries, I would throw balls around with the patients in wheelchairs and then when the doctors came in, we would all through the balls at them. Pretty soon we were all smiling because they had hope.”

Duchin wrote Face the Music with Patricia Beard, a former features editor for Town & Country and Mirabella and author of 11 non-fiction books and one novel. Beard interviewed Duchin for the aforementioned program that night and like the audience, her admiration for her subject was apparent.

In his own recovery, Duchin spent many months fitting pennies into a piano-shaped bank to strengthen his left hand, which was affected by the stoke. “I can move it, but somehow the message doesn’t get down to my hand from my brain to play, but we found a solution. I play with my right hand and our bass player duplicates the sound the left hand would make. We are playing gigs almost every week,” he explained.

Along the way it was not only his wife Virginia and his amazing assistant Adelle who pushed him to recover but also the power of the parents he lost at such young ages. His pianist father, Eddy Duchin, died when Peter was 12, and his mother, socialite Marjorie Oelrichs, died when he was only 6 days old.

During his recovery period, his bed was moved into his downstairs study, his wife placing beloved Cecil Beaton photos of his parents right onto the bookcase for him to look at daily. “Imagine, if you were walking down the street, and you suddenly passed your mother and you didn’t recognize her, and she didn’t recognize you? That is how I felt. I always visualized her and always missed her,” he shared. “It was in this period that I finally got to know them in a way. Although I don’t remember anything of the time I was on the ventilator, I think I did sense their presence.”

Duchin lived with Averell Harriman and his second wife, Marie, until he was nine years old. His mother’s best friend, Marie was very much like a mother to him: “My own mother was not only beautiful and charming, she was unusual. She was a society girl, growing up at Rose Cliff in Newport, but she wanted to work. She had a shop in New York and also posed for Lucky Strike.”

While at Yale, Duchin decided to take a junior year abroad to study French at the Sorbonne. He lived on a houseboat on the Seine and was having a marvelous time.“One day as I was in a state of undress with a young woman when I heard the banging on the boat’s hatch. When I opened the hatch and looked up, I saw well-polished shoes, then pinstriped suit pants: there was Averell. He was a little 19th century, a little aloof, and not the type you want arriving at a time like that. He had my return ticket to New York in hand. I think he had heard I was having too much fun in Paris,” Duchin remembered.

His immensely popular father had been one of the earliest pianists to lead an orchestra and was known particularly for his jazz music. The Eddy Duchin Story, starring Tyrone Power, was the heartbreak film of 1956 chronicling the Duchins’ great love affair and then early deaths.

“I took some of my Yale friends over to Central Park where they were filming to see Kim Novak who was playing Marjorie,” Duchin said. “She was putting on makeup and was a little surprised when I came up from behind and gave her a hug and said, ‘Hi, mom.’ I had never met her before.”

He continued, “My father was in the Navy in World War II, fighting on several battlefields in the Pacific. When he returned, he wanted me to take piano lessons and to set up two pianos so we could play together. He wanted to make a big effort to get close to me, but it never happened. My dream was always that he hadn’t died and when I was playing in the Maisonette Room at the St. Regis, he would be playing at the Waldorf.”

He recalled that in the heyday of café society, the inhabitants came from many walks of life—they were joined by the noteworthy, by people in the entertainment business, and more: “today you often find that manners are missing,” he noted.

We asked Chicagoan Jay Tunney, whose book about his own famous father, boxer Gene Tunney, and his father’s close friend, the author George Bernard Shaw, is being adapted into a play by Theater Wit called Shaw vs. Tunney, to share a little about Duchin: “Peter is my oldest friend, dating from childhood when we played on the beach in Hobe Sound, Florida, during World War II, and he’s never changed. One of Peter’s most endearing qualities has always been that he’s the kind of guy who can talk to anyone, and who, importantly, is actually interested in almost anyone’s conversation regardless of their station in life, their job, their background, or their social or political connections. Perhaps it’s because he finds he’s often being asked about himself that he prefers to steer the conversation away from himself and to hear other people’s stories about themselves.”

He added, “He’s a rare friend who listens well. He’s intuitive and observant and has that natural driving curiosity. You rarely hear Peter refer to himself, unless you ask, and he’s loyal to the bone to those he loves. We’ve been together often as brothers might, many meals, travels, and talks over the last eighty years and even if there’s a lapse of time, I always feel Peter and I are starting where we left off before, whether it’s been hours, weeks, or years.

Tunney said they were alike in that both had famous fathers and grew up in homes of privilege, but that didn’t define them. Though Duchin is treated in public as a celebrity, he is far more complex than just that one identity.

“When I moved to Asia, he came over to visit me, and he was the first to greet me back home. When I decided to write a book on my father, he was the first to encourage me, as I encouraged him when he wrote his first book,” he recalled. “His soaring talent as a musician is well-known, and he deserves world-wide recognition for his music, but Peter is more than a music man, he’s an uncommon man with the invaluable gift of sharing life itself with a common touch.”

Duchin’s books, including his latest, Face the Music, are available wherever fine books are sold.