BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

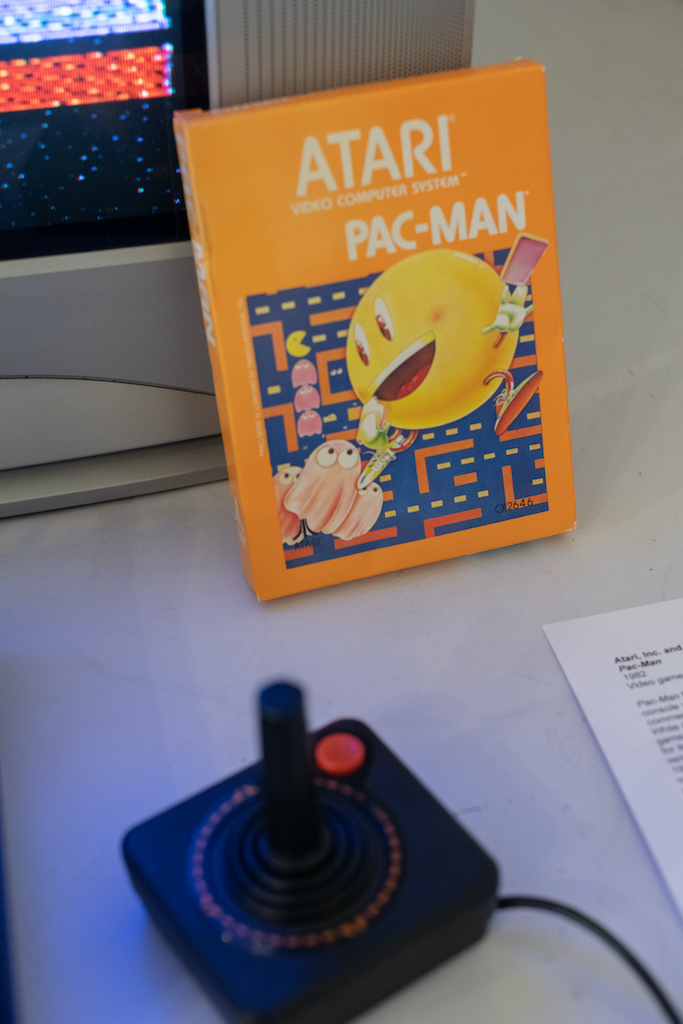

Academically trained as an art historian with 15 years of experience in art museum philanthropy, Jonathan Kinley is Executive Director, Philanthropy, at the Art Institute, where he proudly works with the museum’s close friends and supporters to realize important exhibitions and acquisitions and secure support for operations. In his spare time, he collects and exhibits his growing personal collection of video games at a part-time Airbnb, part-time video game museum called Chicago Gamespace. It now celebrates Pac-Man, its history, design, and legacy through May 30, showing how one man’s hobby can capture likeminded enthusiasts.

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

Kinkley outside Gamespace. Photo courtesy of Chicago Gamespace.

“My wife and I had an Airbnb which quickly became the place where I stored my collection of video games, playable arcade cabinets, artifacts, and ephemera. The idea of opening it to the public Sunday afternoon soon evolved,” Kinkley says. “For our Pac-Man show, we have seven playable games downstairs and upstairs, its history through the years, and media interviews with Toru Iwatani, the Namco video game designer who created Pac-Man. Because of its popularity, we have had to open on Saturday afternoon as well.”

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

Kinkley explains that if it were not for Chicago and its Midway Games, Pac-Man would never have become an international household name. Created by Namco in Tokyo in the late 1970s, the game was not a runaway success in Japan. It was when Pac-Man was introduced into the US market, where its expansive design and global marketing and licensing made it the game everyone quickly wanted to play. It went on to become the highest grossing arcade game of all time.

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

“Pac-Man broke with extant arcade genres and evolved game technologies. In addition to the games, the symbols appeared everywhere: on clothing, posters, backpacks, you name it. It had a huge world impact. The big issues that people have about video games are that they are too violent and they are primarily for young male audiences. Pac-Man was non-violent and was played by young and old, men and women, from the first. They were working at the time with tight technological restraints, but the graphics have held up even today. It has influenced many other games such as Mindcraft,” Kinkley says. Tim Lapetino, author of Art of Atari, serves as the exhibit’s co-curator. In July his definitive book on the subject, The Official Pac-Man: Birth of an Icon, will be published.

With Tim Lapetino. Photo courtesy of Chicago Gamespace.

Kinkley points out that we are almost all game players of late: “During COVID, the video game industry has seen double-digit increases. Games like Animal Crossing have become popular and virtual reality (VR) has really taken off—these are incredible feats of engineering.”

“They are great methods of diversion and escape, whether it is solitaire on your phone or Mindsweeper, which is a single-player puzzle. I grew up with the Sierra King’s Quest games, which still have a special place in my heart,” he continues. “My eight-year-old daughter Charlotte’s favorite, which I play with her, is Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Finding magical horses in the game and dressing them up is a very happy project.”

Kinkley remembers his first sighting, at a Pizza Hut when he was just three years old: “It was out on something like a cocktail table, and I always remember how the colors looked and the sounds exploded and how much fun the kids were having with it.”

Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

He explained that big manufacturers of games such as Mario and Minecraft dwarf film and television in terms of revenues. The tools to develop these games have been democratized, making room for independent producers: the sound person might be in Amsterdam, the animator in Paris, and the programmer in Chicago.

As games are each unique and interactive, combining sound, theater, game play, and even fine art. Kinkley believes that like film and photography, games have a long path ahead. And with manufacturers making efforts to develop games that are entertaining but not addictive, the path is becoming one more people can feel comfortable walking down. “Video games are great diversions and escapes, but some people take it too far. Developers are cognizant that this need to be addressed and most make sure that they are positive things,” he says.

After a long career in video games, artist Jordan Mechner looks to life and art history for inspiration in his works on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Chicago Gamespace

Jordan Mechner, Avenida de Gaudi, 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Chicago Gamespace

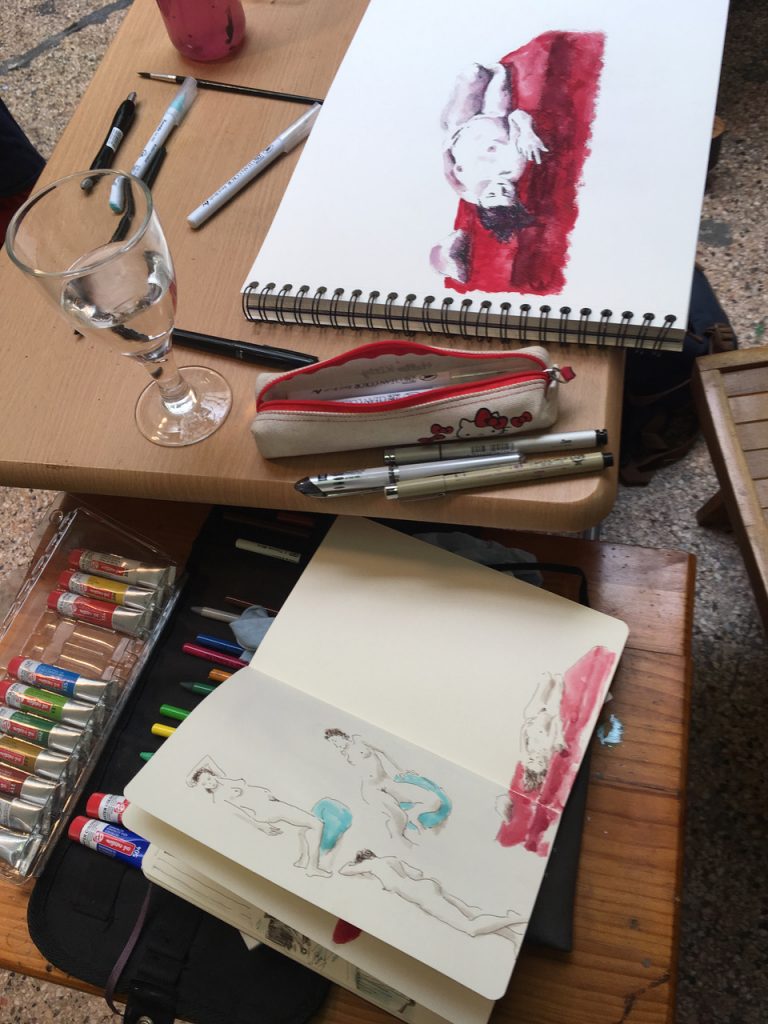

Life drawing sketches by Jordan Mechner, Courtesy of the artist and Chicago Gamespace

The art of Jordan Mechner who made Prince of Persia in the 1980s will be Gamespace’s next exhibit, opening June 4. He became one of the few video game makers to adapt a game to the big screen with Disney’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, who made it into a huge franchise. The exhibit will include Mechner’s sketchbooks and architectural and life drawings.

A screenshot from the hit 1989 Prince of Persia game, designed by Jordan Mechner, that started a franchise comprised of countless video game and film adaptations. The artist was a pioneer in rotoscoping animation in video games and the game distinguished itself from cartoon-like games at the time. Courtesy of the artist and Chicago Gamespace

Vintage console. Photo courtesy of Nathan Keay and Chicago Gamespace.

At Gamespace, Kinkley plans exhibits of video games that have stood the test of time. Included in his collection is a Magnavox Odyssey, the first commercial home video game console from 1972. “It has been fun to develop my own personal collection and share it with the world,” Kinkley shares. “Electronic entertainment can be pure fun and many want to carve out a space for it in their lives. I think what P.T. Barnum said applies here: The noblest art is that of making others happy.”

“Nom-Nom: 40 Years of Pac-Man Design and History” is open for viewing Saturdays and Sundays, 1-5 pm until May 30. Tickets must be purchased in advance; admission is $5, kids under 12 may come for free. Learn more at chicagogamespace.com.