By Francesco Bianchini

She entered the service of my great-grandmother when she was barely a teenager. Petite in features and stature, she would stand on a stool, resting her elbows on the pastry board while being shown how to roll out the dough. When grandfather Francesco – still a young bachelor – crossed her path, after learning her name, he asked out of the blue if she knew how to make acquacotta.* That question confused Nazarena, red in the face, not knowing what to say. There are no photos of her at that time, and I have to use my imagination to picture her as a young girl. Certainly, around the age of sixteen her womanly features began to reveal themselves, and men began to ogle. The first proposal – whether serious or playful in intention – left its mark; Nazarena fantasized for the rest of her life about what might have been.

Around 1928 my great-grandfather Giuseppe hired a Russian émigré as a chauffeur, the sort that could be found in great numbers in the capitals of Europe following the October Revolution; many of them in need of work to survive. The fact that he had escaped with his family from the Bolsheviks was guarantee enough for a great-grandfather who wasn’t too fussy about references. To everyone, the driver was simply Nikita or Vladimir – I no longer recall his first name – but I picture a tall young man with Scandinavian features, fine pale hair, grey eyes, wide cheekbones, and a strong jaw. In short, he wouldn’t go unnoticed.

Several years older than Nazarena, the chauffeur buzzed around her every time he ferried grandfather and his family from Rome to Umbria. One day in the kitchen of Collevalenza, in stunted Italian, the Russian announced that when she was eighteen, he would take her as his wife. Things, however, took a different turn. A trivial circumstance revealed the true identity of the man: he was the son of Prince Volkonsky, a diplomat at the Russian embassy in Rome, and a relative of that Volkonsky – Tolstoy’s cousin – who served as a model for Alexei Bolkonsky in War and Peace. Learning this, Giuseppe invited the man for a glass of champagne to celebrate his son’s engagement to my grandmother Margherita. But Volkonsky scornfully declined, declaring he only drank with his peers. In all likelihood, it was in the company of some of them, and during a copious binge, that he smashed my grandfather’s Studebaker limousine. Giuseppe did not think twice about it: he fired the prince, and thus the marriage with Nazarena went out with a bang.

Over the years Nazarena became the favorite maid of my great-grandmother Sofia, the one confidante of her secrets and her most intimate thoughts. Until saying goodnight, she’d sit at the side of the bed, yawning sleepily as Sofia, supported by a pile of monogrammed pillows impregnated with eau de cologne, insisted on playing another round of solitaire – maybe this time a winning hand. Great-grandmother’s health declined to the point that she was bedridden, but this did not prevent her from controlling people and things; to command from her bed, and to continue receiving visitors in her bedroom that would, after her death, become my father’s study. In her time an extraordinary new object had been placed in a corner with the intention of enlivening her long and monotonous evenings. Depending on Sofia’s moods, the other inhabitants of the house were invited to attend evening programs, but when she was changing for the night, Nazarena was instructed to turn the device off so that ‘the television people’ could not see her. So everyone could view the screen, in a seating arrangement dictated by hierarchical precedence, the television was placed far from the bed. Sofia, whose eyesight had deteriorated considerably, followed those first broadcasts using theatre binoculars with which she also scrutinized her visitors. Who is that woman? she demanded of Nazarena. Why, it’s your daughter come to see you, ma’am, Nazarena replied. Can’t be! Look how ugly she is! Do send her away! My grandmother Anna – she with a squint and touchy nature – took it badly and went away grumbling; her relations with her mother soured between the wars when she married a Frenchman.

I remember Nazarena already advanced in years, endowed with formidable breasts from whose extremities her dresses plummeted down. Her hair was dyed blue, and I happened to witness the miracle of that creation while she sat, impassive to the teasing of her daughter as she applied the famous mixture. Spikes of hair pointed in every direction, like a starfish, before being coiled into place like cresting breakers – a beautiful and rough sea, yet not a tempestuous one. Just the same as Nazarena’s temperament: gruff but willing to break into a hearty, throaty laugh. And when she was unhappy, Nazarena didn’t fail to speak up. The world for her was never immutable, rather constructed like a stairway: there are those who go down and those who go up, she’d say, and an elevated station in life had to be earned, above all, maintained.

I recall one thing that never sat well with Nazarena: my family enjoyed the somewhat feudal privilege of privately accessing the choir loft of the parish church through a passage over the street from a salon in our house. From that balcony, on high, we attended mass. No matter how hard the villagers tried to ignore us, not one missed tallying those of us who were skipping the service; noting what guests were visiting, pondering who might be indisposed, or spying those of us who might be picking our nose in plain sight. Our crossing en masse back and forth – since there was no stairway between the loft and the nave below – was a source of discontent for Nazarena who disapproved of our parading back from communion ‘past toilets’ and other prosaic places with the consecrated host still in our mouths.

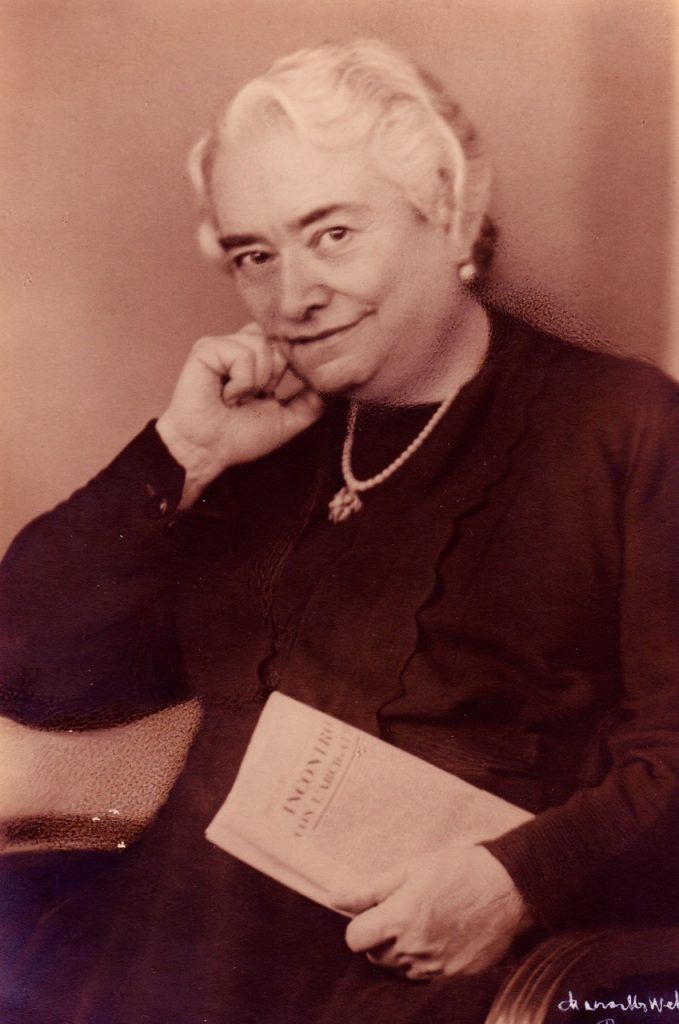

Before she passed away in her nineties, I invited Nazarena to dinner at my very first bachelor apartment. She arrived, driven by car to the front door, dressed in silk and wearing her pearls. Her eyes twinkled, a bit watery from old age, but her hair – that trademark blue hair – was shiny and soft, outlining her forehead and continuing the arch of her nose, and seemed to sparkle with all the diamonds of the Romanovs.

*A long time later I discovered that what I thought was a joke of my grandfather’s – cooked water – was actually a tasty dish. In memory of Nazarena, I sometimes prepare acquacotta using the first tomatoes of the season, two golden onions, chopped celery, chili, fresh basil, and – of course – plain tap water. When it has all been boiled and remains simmering, the final touch is to stir in an egg, a good dose of grated pecorino cheese, and slices of toasted garlic bread to adorn the bowl.