By Megan McKinney

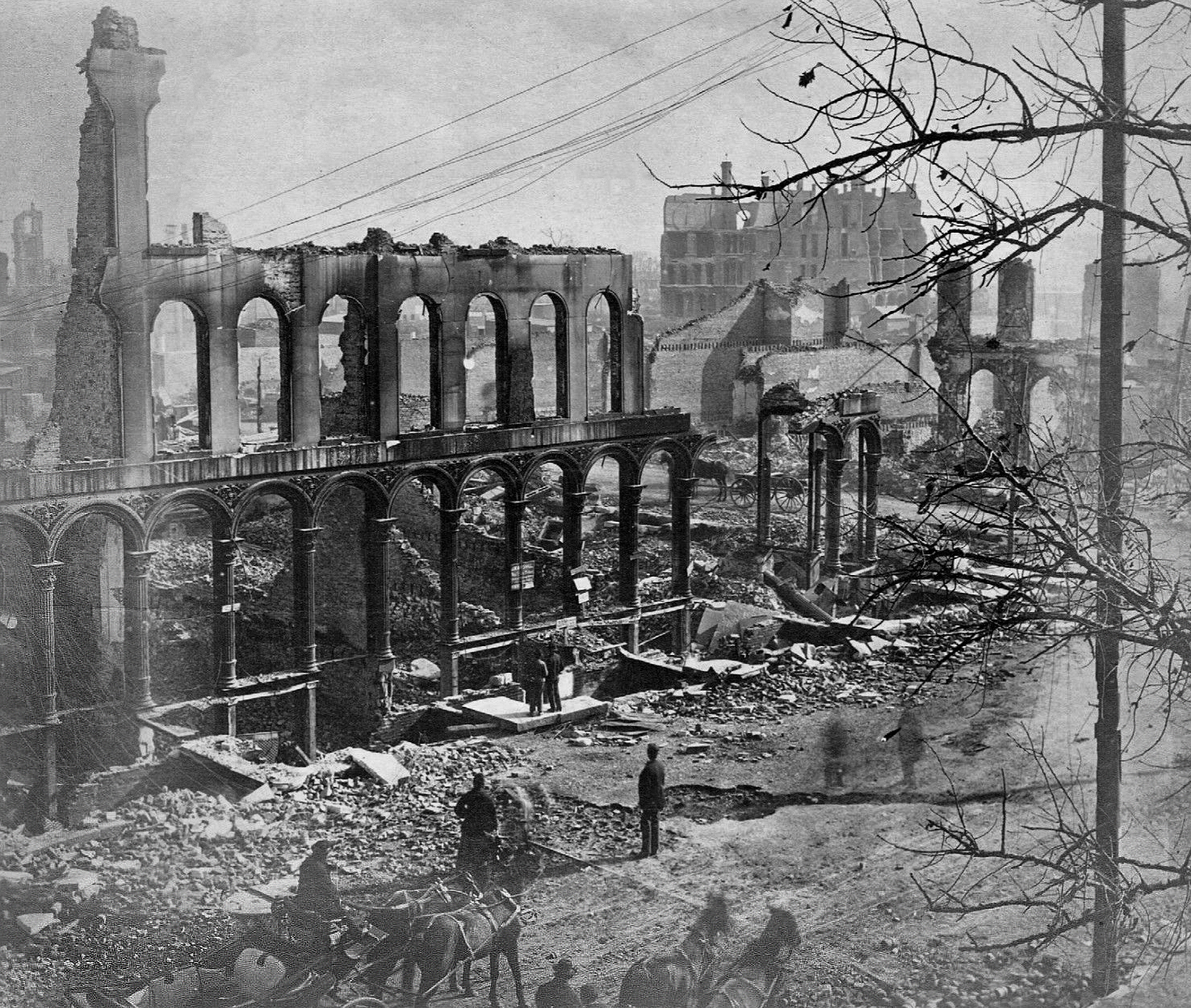

Chicago in the ashes of October 1871.

Twenty-eight-year-old Montgomery Ward had spent half his life working when the Great Fire destroyed the dry goods inventory he had assembled for his embryonic mail-order business, wiping out his savings. Like much of his generation, he faced the destruction with courage and resilience. However, there was another surprise on the horizon.

The rudimentary catalog Monty had mailed to a list of farmers, a sheet with an account of his modest dry goods inventory, had received no response. Even if the goods stashed in a loft above a North Side livery stable had not vanished in the flames that had taken so much, he would have no use for them.

Monty was faced with the possibility that his mail-order plan was the pipe dream others thought it to be. At the very least, it was now clear to him that he was a stranger to the farmers to whom he had sent the inventory of goods with their prices; they had no reason to trust him or believe they would receive goods for money sent. It was then he realized the true hurdle to achieving his mail-order goal was to gain the trust of a distant customer. It was a bumpy time during which he enlisted two partners, George Drake and Robert Caulfield, both Pardridge Company colleagues. The trio was wrestling with the problem of how to gain the confidence of customers to whom they were faceless strangers when one of the nation’s periodic economic panics hit and both partners withdrew.

Then, amazingly, two nearly miraculous plot twists occurred in the Montgomery Ward story, surprise developments that moved his mail-order dream along rapidly.

George Robinson Thorne.

During the years, since their initial chance meeting in St. Joseph, Michigan—described in the previous segment of this series—fate brought Monty back into contact with George Thorne several times. The former major had left the regular army, married Ellen Cobb and joined her family’s lumber business. Ward’s relationship with the Thornes was strengthened not only by the periodic moral support George gave to his mail-order dream but also by the opportunity it gave him to be with Ellen’s younger sister, Elizabeth Cobb.

Throughout their revived friendship, George Thorne had been almost alone in believing in Ward’s mail-order dream and had given his friend great emotional backing and encouragement; however, now—in 1872—he suddenly announced he would join Ward as a partner in the business and bring with him modest, but essential, capital. Thorne’s decision to throw in with Ward was the first pivotal event that changed everything very, very quickly.

Almost immediately, the two learned of The Grange, a six-year-old fraternal organization, officially The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry. The Grange did not have to prove itself to America’s farmers—The Grange was America’s farmers. The essential development came through Ellen Thorne’s uncle, who had a connection with the organization and enabled the two partners to establish a relationship with the Illinois Grange, which enlisted their little company as purchasing agent for its consumer cooperative. Not only was the blossoming Montgomery Ward & Co. made supplier for Grange members, but Monty and George also received access to mailing lists along with an identity, allowing them to develop the Montgomery Ward catalog. At last, Ward’s business began to mushroom.

A classic RFD mailbox. Rural Free Delivery brought the world to the farmer’s front gate, and then to his front door.

The Grange was Ward’s sugar daddy in many ways. The farming organization’s governmental arm had begun to lobby state legislatures and Congress for political goals, including eventual legislation that would greatly benefit Ward—as well as the farm population at large—Rural Free Delivery, in which the United States Post Office distributed mail to the then immense number of little farms throughout the nation. Ultimately, RFD mail—including package deliveries—would be transported directly to farmhouses, an added inducement for farmers to shop by catalog.

By 1874, the partners were distributing a 32-page booklet, which grew incrementally over the next years until, in 1897, they were mailing 1,000-page catalogs. The ground-breaking slogan, “Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back,” was initiated in 1875 and proved effective in reassuring customers who might continue to be wary of shopping for goods they could neither see nor feel.

Note the Original Wholesale Grange Supply House message.

In addition, the mail-order industry as a whole would benefit from a Post Office decision that catalogs fell within the “educational material” category and could be mailed at a reduced rate.

From a 32-page booklet in 1874 to the 1,000-page catalog of 1896-97.

On a personal note, in 1872, Thorne and Ward had become brothers-in-law when Monty married Ellen Thorne’s younger sister Elizabeth Cobb.

It didn’t take long for Montgomery Ward & Co. to become an almost mythical component in American popular culture. When farm families from across the nation visited Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the Montgomery Ward Building on Michigan Avenue held nearly as much interest for them as the White City. Urban residents wanted to see Marshall Field’s; small-town folk and farmers were interested in Montgomery Ward’s.

The Montgomery Ward series within Great Chicago Fortunes will continue next with Montgomery Ward and the Bean.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl