By Megan McKinney

One of Narcissa Niblack Thorne’s exquisite miniature rooms in The Art Institute of Chicago.

When, in 2005, Forbes magazine named Aaron Montgomery Ward “the 16th most influential businessman of all time”, it was quite a statement—and yet…

If we were playing the It’s a Wonderful Life game, think what both retailing and the popular culture of past century and a half might have missed without the existence of Montgomery Ward, a real life George Bailey.

Our most recent three articles have reminisced about some of the activities of the amazing Mr. Ward.

First, he created a new industry, an industry no one had imagined previously; it was so new that of the handful of men who eventually understood it only one believed in the revolutionary concept strongly enough to drop his own business to become—and remain–Monty’s partner; he was George Robinson Thorne.

Before Montgomery Ward & Co., retailing had always taken place in stores, possibly from wagons or door-to-door, but not by catalog. Ward literally invented the mail-order concept, which not only paved a path for Sears Roebuck, the Spiegel Catalog and other mail-order companies but it also created a niche for Amazon, the company further revolutionizing retailing in our own time.

Then, we have Millennium Park, which—along with Grant Park—exists in a long band of grassy land kept clear of industry, thanks to a slice of the Montgomery Ward fortune, which the mail order magnate chose to spend fighting extended greed so that each of us could enjoy a utopian city bordered with clear blue water, fragrant green grass and fresh clean air.

Perhaps it’s a stretch to throw in the delightful, life-enhancing Thorne Rooms but would their creator, Narcissa Niblack Thorne, have had the ability to be as wildly generous with her talents were there not the Montgomery Ward fortune?

Let’s just say her position as the daughter-in-law of Monty Ward’s partner, George Thorne, gives us an excuse to visit this extraordinary woman whose life is closer to our time than those we customarily choose to scrutinize in our Classic Chicago historic series.

Narcissa Thorne

Narcissa Thorne

George Thorne and his wife, Ellen, produced seven children, creating a major Chicago dynasty, which soon dominated leadership of Montgomery Ward & Co. and began connecting with other important area families. The Thorne’s eldest child, Laura Belle, married printing heir Reuben H. Donnelley, a major stockholder of Wards, who increased his family fortune and visibility by establishing the company that produces the Yellow Pages.

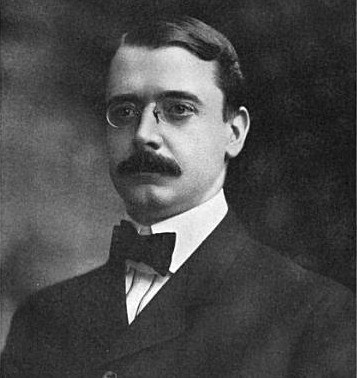

Reuben H. Donnelley.

Two of the Thornes’ sons, Robert Julius and George Arthur, were Wards presidents, and Robert’s daughter, Ellen, a prominent ornithologist, married Hermon Dunlap “Dutch” Smith, grandson of Perry H. Smith.

Robert Julius Thorne.

It was George and Ellen’s second son, James Ward Thorne, who married Narcissa Niblack and, in doing so, soon gave the Thorne name new luster.

Narcissa had been born in Vincennes, Indiana to a Virginia-raised mother and a lawyer father with Mayflower ties. Following the family’s move to Chicago’s Hyde Park area, Narcissa’s education consisted of governess tutoring until age 11 and finishing at Kenwood Institute. She was 19 when she married Princeton graduate Jim Thorne, who had been her childhood sweetheart.

This Thorne son appears to have been much less driven than his brothers Robert and George. Although he served as a Wards director and vice president, he was never president and retired from the company in 1926 at 53. The couple who had two sons, Ward and Niblack, maintained households in Chicago and Lake Fores

Edwin Hill Clark was architect of the French Renaissance-style chateau built in Lake Forest for the James Ward Thornes in 1910.

Narcissa appears to have been a hospitable lady, at least according to the diaries of Ginevra King, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s model for The Great Gatsby’s Daisy Buchanan, who wrote in her teen age diary more than once of “swimming over at Mrs. Thorne’s” in the morning and staying on for lunch. On one occasion she mentioned that also at lunch were “about 30 people”.

After Jim Thorne’s retirement, the pair traveled incessantly, especially to European cities with numerous antique shops, many with quantities of fine miniatures.

Narcissa, who had grown up receiving tiny replicas of furniture sent from throughout the world by an admiral uncle, had been drawn to miniatures from an early age. The diminutive furniture she acquired during travels with her husband required a series of appropriate environments, so boxes were built to house them and craftsmen sought out to create other furnishings to complete each room under her direction. The famous Thorne Rooms grew from there.

Mrs. Thorne personally designed many of the miniature replicas of rooms, dating from 1600 to 1940, and worked with a spectrum of craftsmen in her North Side studios to produce them in painstaking detail, often working seven days a week and spending thousands of dollars on a single tiny setting. The rooms had the dual benefits of creating work for highly skilled crafts workers during the Depression and educating the public in the history of interior design.

Even Edwin Hill Clark, architect of the Thorne’s Lake Forest house, was enlisted to design of some of Mrs. Thorne’s miniature rooms. In creating the vignettes she established the one-inch-to-one-foot scale for miniatures that has been accepted as the standard ever since.

The initial presentation of Narcissa’s rooms appears to have been a 1932 reception at the Chicago Historical Society where 30 replicas of American and European rooms were displayed more or less privately. The first time the public saw the rooms—to great acclaim—was when they were exhibited in their own building at the 1933-34 Century of Progress Exposition. Then, in 1937, they made their Art Institute of Chicago debut. Next they were featured at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, followed by the 1940 World’s Fair in New York.

Somehow, within a schedule of travel, entertaining and seven-day-weeks of creating miniature boxes, Narcissa managed to be active in charitable works. She raised and contributed funds to the Art Institute, Chicago Historical Society and the Women’s Exchange on North Michigan Avenue, where for many years she housed her studio. She was also devoted to the city’s leading hospitals and, although she participated in activities on behalf of both Rush and Children’s Memorial, it was the current Northwestern Memorial on whose Woman’s Board she sat from late 1931.

She is particularly remembered for the crèche she installed in Northwestern’s Passavant Hospital lobby at the beginning of the Christmas season each year, using rare figurines she had found in Italy. This she did alone, trusting no one else to handle the fine ceramics.

Jim joined her as a generous supporter of Northwestern Memorial Hospital. At his death in 1946, funds were left to the hospital which established the much needed James Ward Thorne School of Nursing, notable for years for its chic student uniforms designed by the great couturier Mainbocher.

Mainbocher with from left Mrs. Loyal Davis, whose daughter Nancy was Mrs. Ronald Reagan, Mrs. Leon Mandel, modeling the nursing uniform, Mrs. James Ward Thorne and Mrs. Alden B. Swift.

The $2 million Narcissa personally inherited on Jim’s death increased her personal ability for both charitable generosity and creative splendor.

This segment concludes the Montgomery Ward series within Great Chicago Fortunes.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Selected Photography Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago