Twice a Chicago Giant

The Montgomery Ward catalog would be quite a retailing breakthrough—but only the beginning for an amazing man

By Megan McKinney

Of the men who built Chicago’s great industries, while making immense fortunes for themselves and their heirs, there could not have been one with greater concern for the well-being of his clientele than Aaron Montgomery Ward. But he was also an extremely effective tycoon.

Ward almost single-handedly created one of the nation’s towering industries—mail order—from a completely original concept. Although in retrospect the catalog business would appear to have been a natural extension of Chicago’s phenomenal dry goods industry, it was not. And it would seem that once the concept was fully explained, anyone could grasp its power. No one did. In fact, even after Monty Ward had hammered together an effective plan—one that would revolutionize American retailing up to and through today’s Amazon—others reacted to him as they might a borderline lunatic.

There was something else, something very important. Although our city has no museum, educational or aesthetic reminder bearing the Ward name, he may well have contributed as much as any man, or woman, in the history of Chicago to the quality of life each of us enjoys every day, a facet of the man to be studied in the third segment of this four-part series.

An American farm of the 1850s.

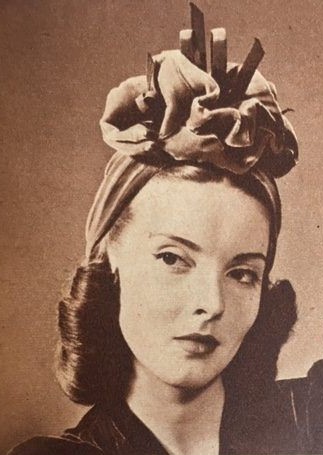

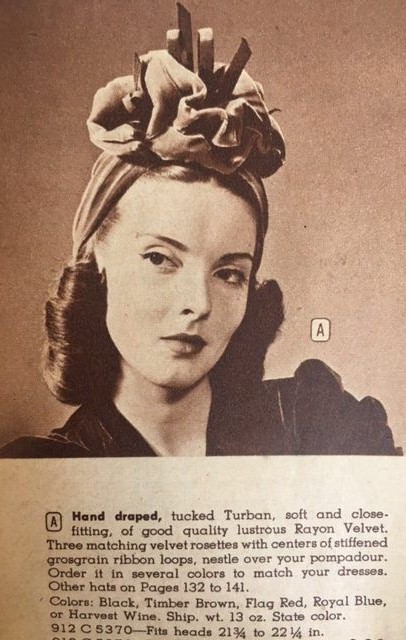

The catalog model emerged from Ward’s genuine respect for farmers. His father, Sylvester Ward, had been a farmer until he was hoodwinked into giving up his Chatham, New Jersey farm for a well-stocked general store in Niles, Michigan. When the family arrived in Niles to begin a new life, the store was there on Main Street, but its reported stock—dry goods, shoes, notions and kitchenware—was not. The dejected family, including eight-year-old Monty, moved into the empty stockroom at the rear of the deserted building, and Sylvester found a job clerking in a local hardware store.

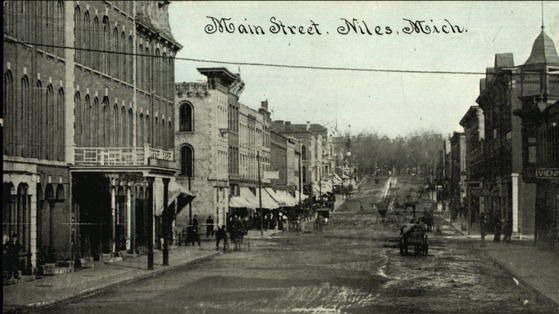

Main Street, Niles, Michigan, home of Sylvester Ward’s empty new store.

Six years later, 14-year-old Monty secured a full-time position doing “odd jobs” at the local Jones & Chapin Barrel Factory and contributed his 25 cent daily pay to the family upkeep. This lasted almost a year—until Monty took a job in a brickyard owned by the same Jones and Chapin. His wages doubled to 50 cents daily for the 14-hour, six-day-a-week, backbreaking job of loading brick on scows for shipment down the St. Joseph River.

After two years, Monty caught the attention of a Captain Boughton, owner of a fleet of brick-carrying scows; the captain also owned a flimsy bartering business in St. Joseph, Michigan, across Lake Michigan from Chicago. Boughton was impressed enough with the young man to hire him to work in his rudimentary St. Joseph store; it was less money than young Ward had been making and again it was “odd jobs,” but there was no heavy lifting and a possible future in the Captain’s quasi-shop.

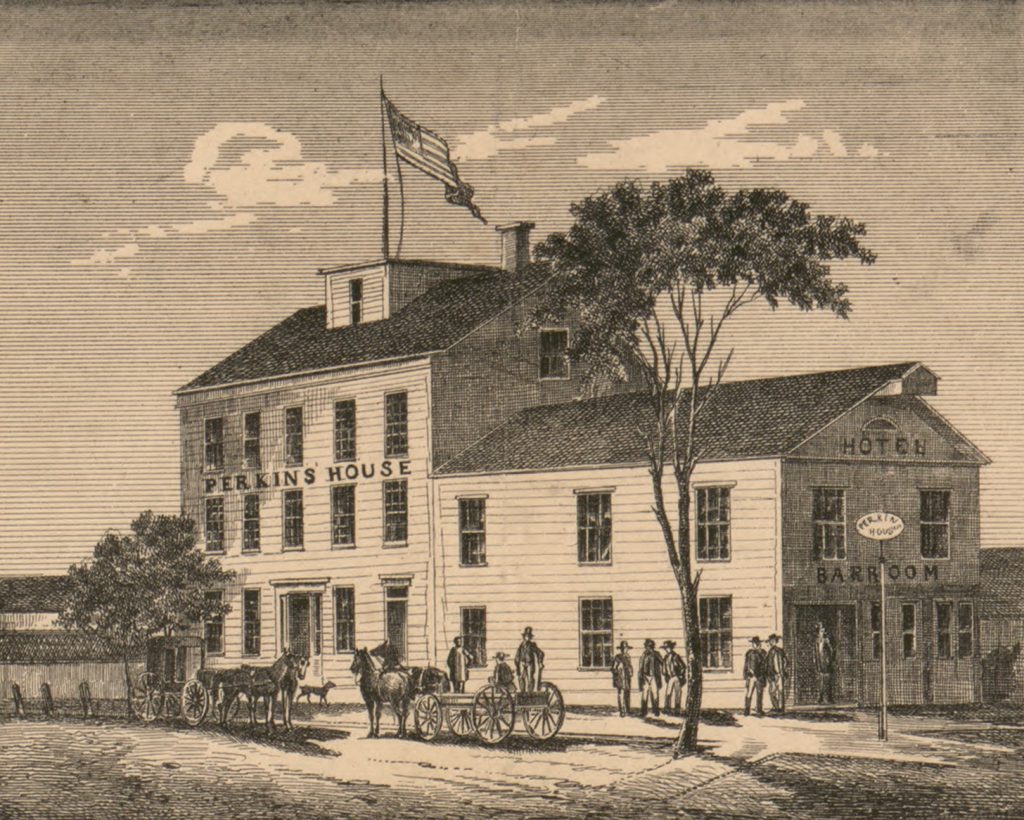

Perkins House hotel was part of life in mid-19th century St. Joseph, Michigan. Twenty-first century St. Joseph is well known to many Classic Chicago readers, some of whom spend weekends and summers in the area.

Thus, young Ward was again immersed in the farming world of his childhood; however, this time it was two worlds, a combination of farming and merchandising—and together they produced the first glimmer of the strong feelings the merger of the two would create to transform his life.

When Monty saw the captain’s shop, he was appalled. Heaped in big boxes and crates, sometimes spilling out and onto the floor, were goods for the farmers to acquire. Also strewn about helter-skelter was produce the farmers had delivered for barter—peaches, cabbage and roasting ears to be exchanged for women’s shoes, children’s suits and oilcloth. Even more dismaying to the young man was the quality of goods being offered—low-end, sometimes incomplete or damaged—accompanied by an arrogant manner toward the country folk.

Within two years, the appearance of the store had been transformed and Monty was now in charge. Both produce and goods were presented in orderly fashion, on shelves, tables, counters or in attractive bins. Inferior merchandise from wholesalers was refused, farmers were treated with dignity and Captain Boughton’s haphazard side business was making money. As a result, Monty’s pay had skyrocketed from $5 to $100 monthly.

Farm families coming to town for the day, bringing box lunches with them, were accepted hospitably. Monty installed long tables and benches in a grove behind the store, and the families gathered there for lunch. They knew they were welcome to drink water from the captain’s well, and Monty had added a swing and teeter-totter for their children.

Kalamazoo, Michigan during the mid-19th century.

One day in July 1865, a young army officer, a major in the regular army, arrived in the store, asking Monty if he and three women he was escorting to a steamer in the harbor could “trespass” in the picnic grove. The officer was Major George Robinson Thorne and the ladies were Ellen Cobb, a young woman Thorne hoped would become his fiancée, her younger sister and their crotchety mother.

The little group had come to St. Joseph by train from Kalamazoo, Michigan, for the three women to board a steamer that would take them across the lake to Chicago for a week. George Thorne merely wanted a place for the ladies to sit, where they would be out of the heat until the steamer was ready. Monty not only welcomed them into the picnic grove but also sent out for ice cream for the little group. He was delighted with George, who was about seven years his senior, and the two girls, particularly the younger girl, Elizabeth, although she could not have been older than 16. When the women retraced their route in a return to Kalamazoo a week later, Monty met them at the steamer and escorted the ladies back to the train station.

Major Thorne and the Cobb women would reappear in Ward’s life some years later, each playing a significant role.

Chicago in 1870.

Ward had gone as far as he could in St. Joseph and was persuaded by a Field, Palmer, Leiter & Company salesman to move on to Chicago, which he did. After two years working for this antecedent of Marshall Field & Company, he joined a Chicago wholesale company as a traveling salesman, then did the same for a more prominent St. Louis wholesale house, Walter M. Smith & Company. It was a dismal life of traveling from one small Midwestern town to another, staying in seedy hotels and eating in dreary little restaurants or boarding houses.

Although a bleak existence, this was an important period for Ward. It caused him to not really fantasize, but close. His inner life followed a continuing What if? scenario that kept him company during the days and nights when there was nothing else. What if there were a new way to set retail prices? The shopkeeper paid the wholesale price, factored in his expenses, and then he added his profit, which was set by competition with the other stores on Main Street. What if the town was too small to have competition? The profit could be 20 percent, 30 percent, 40 percent.

The thought of gouging farmers and other low-income people was increasingly repugnant to Ward, who was continuing to observe the manner in which farmers were treated throughout his territory. It was the same “anything is good enough for the hayseeds” attitude he had observed in St. Joseph.

What if he saved enough money to start a business of his own? A business without a middle man? A business without arbitrary profit? A business in which goods went directly to the customer for cash—removing the necessity for a store and its maintenance, salesmen, a credit department, and the expense of reaching the customer? It would be a new kind of business, too new to have a name, a business of sending goods ordered—perhaps by mail.

He was recording farmers’ names as he traveled. He planned to send a list of goods and prices to the men who would mail him their orders, which he would fill by purchasing directly from wholesalers, taking a 10 percent profit after expenses. In the style of his former employer Potter Palmer, he was mentally working out a “satisfaction guaranteed or your money back” angle, essential for customers who would pay for merchandise they hadn’t seen. And it was necessary to establish a cash business in order to obtain low prices from wholesalers.

By 1870, he had saved money but would have to keep working—and it should be an office job—until the business paid for itself. Because there was nothing appropriate with Walter M. Smith & Company, his St. Louis employer, he returned to Chicago, where he joined a wholesale dry goods house, C.W. Pardridge Company, as a buyer.

In his spare time, he began assembling modest stock from wholesalers’ odd lots, limiting his acquisitions to dry goods; he would add housewares and other categories as the business grew. The inventory he would send to his list of farmers grew to include yard goods, paper collars, gloves and mittens, socks and stockings, needles, thread, pins, handkerchiefs and other small items, which he stored in a large corner of a loft above a North Side livery stable. In the fall of 1871, ready to begin his business, he mailed the inventory to his list of farmers and settled down to wait.

On October 8, a Great Fire broke out on Chicago’s West Side, sweeping into the business district, then raging north destroying everything in its path, including Ward’s inventory, representing his entire savings. But not his dreams.

The Montgomery Ward series within Great Chicago Fortunes will continue next with Montgomery Ward and the Wish Book.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl