BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Last fall, three Chicago women visited the Lindenwood Cemetery in Stoneham, Massachusetts, to lay flowers at the base of a gravestone they had commissioned. It was a crisp October day, just the right kind of morning Mabel Slade Vickery, Latin School of Chicago’s founder and first head of school, would have loved for her daily walk she led for her students. Latin Archivist Teresa Sutter, who has researched, written, and lectured about Mabel’s extraordinary career and made the Massachusetts memorial stone a reality, told us that Mabel had moxie.

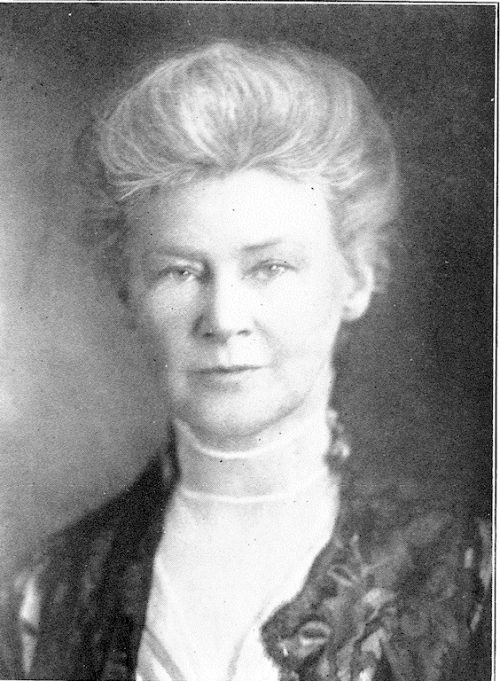

Mabel Slade Vickery.

Teresa says: “Mabel Slade Vickery should be known outside the walls of Latin. She was one of the first educators to practice the Quincy Method of experiential-based hands-on learning, which was a radical notion at the time and is still a method used today. And she was a woman who founded and owned her own school in the 1800s, which was even more radical and rare. She was definitely a self-made woman who knew what she wanted. I felt we needed a permanent way to honor her and share her story.”

The memorial stone, with Latin School medallions placed lovingly at the base showing the mascot Roman, reads: “In recognition of her extraordinary vision, leadership and dedication to excellence in education.” Accompanying Teresa were Alumni Director Stephanie Chu and faculty alumna Ruth Hutton, who were backed by the enthusiasm of Latin’s Head of School, Randall Dunn, seen below in this photo created for a Latin celebration of Miss Vickery’s birthday, a yearly celebration for the school.

Mabel with present-day head of school, Randall Dunn, thanks to the magic of Photoshop.

Teresa, who wrote movingly about the trip in a recent issue of Latin Magazine, told us how her interest began:

“Every day I walked by her portrait at the top of the second floor stairs at Latin and admired her smile and her dignity. Back in 2010 we were coming up on the school’s 125th anniversary, and I started digging into the archives to find what might be interesting for the celebration. The more I read, the more my curiosity was piqued. The letters back and forth between Miss Vickery and her first female student, Josephine Wilkins, were donated to the school in the 1970s. She continued to mentor Josephine, offering advice and the opportunity to share joys and pitfalls. Manners were very important to her, but she is so often smiling in her photos and her sense of humor comes through in her letters.”

A student of anthropology in college who participated on archaeological digs in Ireland, Teresa, who grew up in Towanda, Illinois, has always loved doing research. She taught Native American students in Omak, Washington, and on the Zuni Pueblo south of Gallup, New Mexico.

After locating Miss Vickery’s gravesite in 2016, Teresa had a persistent nagging thought: “Visitors to Miss Vickery’s grave will never know of her pioneering and innovative work in education.”

It took two years to accomplish her mission. Teresa first contacted Donna Tamburrini, office manager for the Town of Stoneham, who became an invaluable resource.

“She verified that there was a space on Miss Vickery’s plot for an additional marker and put us in touch with a local monument company. Our Alumni Office came to learn about the merits of limestone, marble, and granite. In early September, a design was finally approved, and Latin received the cemetery permit,” Teresa shares. “There was just one problem: the permit requested a living relative to sign off on the new marker. Miss Vickery’s five siblings preceded her in death, as did her nephews and niece. To the best of their knowledge she had no living relatives. So how could we get the marker placement approved?”

She continued, “It was suggested that the town government be contacted. I started with the town clerk, who had never heard of a school commissioning a gravestone for someone so long deceased. The town’s selectman was equally baffled. Finally, Tamburrini was able to intercede just in the nick of time, for the cemetery was laying foundations for new markers on the very next week. We were scheduled to be in Boston for alumni events and were able to visit her grave the day after the stone was laid in the ground. To finally be able to honor her, to lay flowers at her grave, meant so much to us because we thought of all the struggles she overcame. The students were so excited we were doing this.”

The memorial stone.

Teresa Sutter, at left.

The school’s first location was in the Blatchford family home on LaSalle Street, not far from the current location at Clark and North. Noting the Francis Parker-Latin School rivalry on the soccer fields and basketball courts, it is fascinating to know that it was Colonel Francis Parker who brought Miss Vickery to Chicago.

“She had been teaching in Massachusetts and Connecticut, using Parker’s rather radical hands-on teaching method, known as The Quincy Method. When Mrs. Blatchford wrote to Col. Parker asking for a recommendation for a teacher to start a school in Chicago based on his method, Parker, recognizing Miss Vickery’s vision and passion for education, immediately recommended her for the job,” Teresa says. “At age 34, Miss Vickery packed up all of her belongings and moved here to found the parent-owned school in 1888.”

Mabel.

In 1896, the school, founded just for boys, became coed, definitely radical at the time. “The McCormick family wanted their daughter, Elizabeth, to get the same education their sons did but were hesitant to enroll her in a ‘boys’ school. Miss Vickery decided she would bring in Josephine Wilkins, a family friend, to show the McCormicks that the school was right for girls as well.”

In 1899 Miss Vickery leased land at the corner of Division and Astor streets and oversaw the construction of Latin’s first school building, which she owned. She rented a small apartment right across the street. Then, in 1913, the Girls Latin School was founded, and there were two separate schools.

The boys.

The girls.

Catherine Patrick Hazlett, a graduate of the Girls Latin class of 1917, remembered with great enthusiasm just before her death at 104 Miss Vickery’s walking club which sometimes had Kenosha, Wisconsin, as its ambitious destination.

“As I researched Miss Vickery’s life, I wanted our students to know more about her and recommended that the school celebrate her birthday on September 13. Randall wholeheartedly agreed, and I met with teachers to tell them more about her accomplishments,” she shares. “Junior Kindergarten students through seniors in high school have found fun and innovative ways to celebrate her, and we even created her own bitmoji.”

A current student celebrates Mabel.

In addition, Teresa has been asked to speak to classrooms about Miss Vickery and often takes visitors and students on a walking tour of the several campuses Latin has had since its founding. She always explains that Miss Vickery insisted that students play outside for 20 minutes a day.

We asked Teresa what Miss Vickery might think if she could time travel to Latin today. Her response? “Our current Project Week, where students have a wide variety of learning both in Chicago and beyond, would probably have blown her away. These field trips exemplify her love of hands-on learning. She would be impressed with our study of Singapore Math and approve that we have kept the small teacher-student ratios.”

Teresa shared one last Miss Vickery story showing the early bonding between Latin and Francis Parker, which might not end playing field rivalry but speaks to Miss Vickery’s loyalty:

“Francis Parker’s educational theories were thought to be so radical that the heads of the Chicago school board wanted to kick the educator off the board. Miss Vickery got in her buggy and drove her horse to the homes of many influential Chicagoans to ask them to intercede. She definitely swayed people. In 1901 Col. Parker asked Miss Vickery to join him as co-principal at his newly founded school, but she declined, indicating that she enjoyed being in charge of her own institution. Thank goodness she did!”

To learn more, visit the Latin School archives here.