BY JOHN A. BROSS

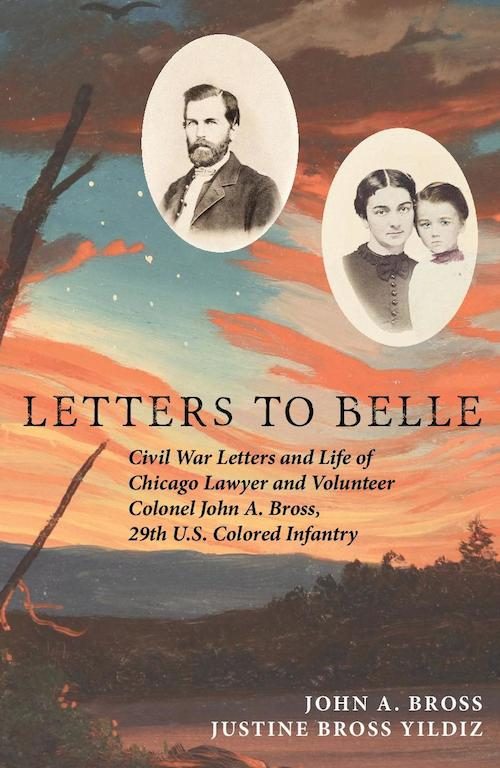

Editor’s note: This article provides a snapshot of Chicago leading up to and during the Civil War as described in the upcoming book, Letters to Belle: The Civil War Letters and Life of Colonel John A. Bross, 29th Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops, as much an examination of the period and its political climate as it is a story of love, loss, and family in the time of conflict. Written by his descendants John A. Bross, of Chicago, and Justine Bross Yildiz, Letters to Belle is scheduled to be published and available on Amazon in July 2018.

In 1848 William Bross, an 1834 graduate of Williams College who had been running a school in Orange County, New York, decided to begin a new life in a small town in the West on Lake Michigan called Chicago, which he thought had good potential for commercial growth. Upon his arrival there in May, he sent for his wife and children, also persuading his favorite younger brother, John, a law student, to join him.

William Bross. Photo courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Chicago, 1830.

The rapid growth of Chicago was beginning to astonish the world. In 1830 it was a village with a population of only 250. By 1840 it had become a town and then a city with a population of 4,500. In 1850, the population had grown to 28,000, more than six times its size in just ten years, and by 1860 Chicago had become the ninth largest city in the United States with 112,000 inhabitants.

1853 Chicago, Birds Eye View.

Two major events in 1848 contributed to Chicago’s growth. The first was the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. This ran from Chicago to LaSalle, Illinois, joining the Illinois River, eventually making its way to the Mississippi River. Shipping could now go directly from Chicago all the way down to New Orleans.

Illinois Michigan Canal. Image courtesy of the Chicago Public Library.

The other major event happened on November 20, 1848, when an 11-year-old wood-burning locomotive called The Pioneer pulled away from Chicago with about 100 stockholders and editors seated in two baggage wagons to open Chicago’s first railroad, the Galena & Chicago Union, which ran just ten miles west from the city to the Desplaines River. On the return trip, a farmer’s wagonload of grain was transferred onto one of the cars, and this was the first shipment of grain by rail to Chicago.

By 1856 Chicago was the focus of ten trunk lines, with 58 passenger trains and 38 freight trains arriving daily. It was said that the Illinois Central Railroad was the first great “St. Louis cut-off” and as such “placed Chicago firmly upon her throne as the magnificent Queen of the West.”

The Pioneer.

Some thirty years later, in 1876, William, by then a distinguished journalist and president of the Chicago Tribune Company, published his recollections of life in Chicago in those early years.

In 1848, before the railroads had been built, a trip west to Chicago was no bed of roses. In his History of Chicago William gave the following account of his journey:

As a specimen of traveling, in 1848, I mention that it took us nearly a week to come from New York to Chicago. Our trip was made by steamer to Albany; railway cars at a slow pace to Buffalo; by the steamer Canada thence to Detroit; and by the Michigan Central Railway, most of the way on strap rail, to Kalamazoo; here the line ended, and, arriving about 8 o’clock in the evening, after a good supper, we started about 10 in a sort of a cross between a coach and a lumber box-wagon for St. Joseph. The road was exceedingly rough, and, with bangs and bruises all over our bodies, towards morning several of us left the coach and walked on, very easily keeping ahead. … The steamer Sam Ward, with Captain Clement first officer, and jolly Dick Somers as steward, afterwards Alderman, brought us to the city on the evening of the 12th of May, 1848.

The Erie Canal. Image courtesy of eriecanal.org.

Once you had arrived, it wasn’t always easy to get around in the city. In his History, William reports:

I said we had no pavements in 1848. The streets were simply thrown up as country roads. In the spring for weeks portions of them would be impassable. I have at different times seen empty wagons and drays stuck on Lake and Water streets on every block between Wabash avenue and the river. Of course there was little or no business doing, for the people of the city could not get about much, and the people of the country could not get in to do it. As the clerks had nothing to do, they would exercise their wits by putting boards from dry goods boxes in the holes where the last dray was dug out, with significant signs, as “No Bottom Here” and “The Shortest Road to China.”

At night, getting around was even more difficult. William relates, “I said we had no gas when I first came to the city. It was first turned on and the town lighted in September, 1850. Till then we had to grope on in the dark, or use lanterns. Not till 1853 or ‘54 did the pipes reach my house, No. 202 Michigan avenue.”

Chicago Water Works. By Louis Kurz, courtesy of Chicagology.com.

The city’s water supply, according to William, presented certain problems:

But the more important element, water, and its supply to the city have a curious history. In 1848, Lake and Water, and perhaps Randolph streets, and the cross streets between them east of the river, were supplied from logs. James H. Woodworth ran a grist-mill on the north side of Lake street near the lake, the engine for which also pumped the water into a wooden cistern that supplied the logs. Whenever the lake was rough the water was excessively muddy; but in this, myself and the family had no personal interest, for we lived outside of the water supply. Wells were in most cases tabooed, for the water was bad, and we, in common with perhaps a majority of our fellow-citizens, were forced to buy our water by the bucket or the barrel from water-carts. This we did for six years and it was not till the early part of 1854 that water was supplied to the houses from the new works upon the North Side.

But our troubles were by no means ended. The water was pumped from the lake shore the same as in the old works, and hence, in storms, it was still excessively muddy. In the spring and early summer it was impossible to keep the young fish out of the reservoir, and it was no uncommon thing to find the unwelcome fry sporting in one’s wash-bowl, or dead and stuck in the faucets. And besides they would find their way into the hot-water reservoir, where they would get stewed up into a very nauseous fish chowder. The water at such times was not only the horror of all good housewives, but it was justly thought to be very unhealthy. And, worse than all this, while at ordinary times there is a slight current on the lake shore south, and the water, though often muddy and sometimes fishy, was comparatively good, when the wind blew strongly from the south, often for several days the current was changed, and the water from the river, made from the sewage mixed with it into an abominable filthy soup, was pumped up and distributed through the pipes alike to the poorest street gamin and to the nabobs of the city. … The Chicago river was the source of all the most detestably filthy smells that the breezes of heaven can possibly float to disgusted olfactories. Davis’ filters had an active sale, and those of us who had cisterns betook ourselves to rain-water—when filtered, about the best water one can possibly get.

William goes on to report that a two-mile tunnel into the lake was opened in 1867, pumping clean lake water into the city’s water supply. It should be remembered that the theories of Lister about the existence of bacteria did not begin to be taken seriously in the United States until the 1880s, so during the 1850s and throughout the war years, people drank water contaminated by animal or even human feces without realizing that this spread cholera and other fatal diseases. William and Jane had eight children, only one of whom, his daughter, Jessie, survived to maturity; it seems probable that a contaminated water supply was the cause of death for at least some of his children.

In spite of the bad streets and bad water, Chicago was a busy city. William reports:

It is a feature of our city, more noticed by strangers than by ourselves, who are accustomed to it, that we are a community of workers. Every man apparently has his head and hands full, and seems to be hurried along by an irresistible impulse that allows him neither rest nor leisure. An amusing evidence of this characteristic of Chicago occurs in connection with the first census of the city, taken July 1st, 1837, when the occupation, as well as names and residences of every citizen were duly entered. In the record of the population of four thousand one hundred and seventy, among the names of professors, mechanics, artisans and laborers, appears, in unenviable singularity, the entry, “Richard Harper, loafer” the only representative of the class at that time in the city. From this feeble ancestry the descendants have been few and unimportant; and we believe there is not a city in the Union where the proportion of vagabonds and loafers is so small as in Chicago.

William adds in a footnote that he was pleased to learn later that Harper was very respectably connected in Baltimore, where he subsequently became the founder of an important temperance revival.

In later years the leading men of Chicago were justly proud of their accomplishments in building businesses in the city in the face of many difficulties both corporate and personal. After listing some of the “men who gave character to Chicago in 1848, and the years that followed,” William notes, in 1876, that:

Some of these gentlemen were not quite so full of purse when they came here as now. Standing in the parlor of the Merchants’ Savings, Loan and Trust Company, five or six years ago, talking with the President, Sol. A. Smith, E.H. Haddock, Dr. Foster, and perhaps two or three others, in came Mr. Cobb, smiling and rubbing his hands in the greatest glee. “Well, what makes you so happy?” said one. “O,” said Cobb, “this is the last day of June, the anniversary of my arrival in Chicago in 1833.” “Yes,” said Haddock, “the first time I saw you, Cobb, you were bossing a lot of Hoosiers weatherboarding a shanty-tavern for Jim Kinzie.” “Well,” Cobb retorted, in the best of humor, “you needn’t put on any airs, for the first time I saw you, you were shingling an out-house.”

William added: “Young men, the means by which they have achieved success are exceedingly simple. They have sternly avoided all mere speculation, they have attended closely to legitimate business and invested any accumulating surplus in real estate. Go ye and do likewise, and your success will be equally sure.”

Many followed his advice.