By Francesco Bianchini

As far as I know my family has always been faithful to the Pope, even at the cost of committing acts of impertinence against the King. My great-great-grandmother’s father was the Apostolic Delegate of Spoleto (i.e., Governor) when the city was attacked in 1860 by troops of Garibaldi. The Papal army sent from Rome was worth very little, composed of a handful of Swiss Guards, with a majority of poor Irish railroad workers, summarily impressed at the last minute to switch their tools for outdated weapons. The city capitulated very quickly. Back in Rome – after the taking of Porta Pia – the Pope’s loyalists, including my ancestors, turned their armchairs, once reserved for visiting prelates, against the wall as a sign of hostility towards the dignitaries of the new Kingdom of Italy. Both my great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather continued to serve the Holy See as gentlemen of honor, called di cappa e spada – of the Cape and the Sword. At sacred functions or special audiences with ambassadors and foreign heads of state, they escorted the Holy Father through the Vatican halls, stairways, and corridors, parading in black velvet doublets, matching tights, starched white ruffs, clanking around with their ceremonial swords.

Garibaldi’s Red Shirts in battle

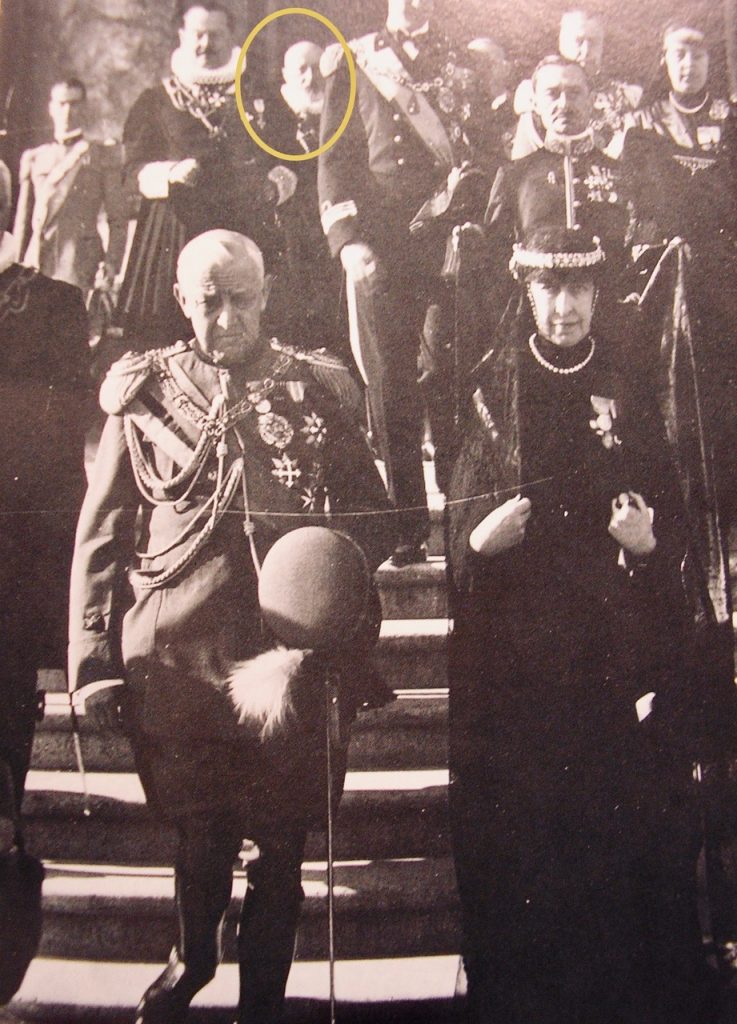

Grandfather Giuseppe (circled behind) helping to escort the Duke and Duchess of Aosta on the Vatican stairs

Not surprisingly, a certain familiarity developed between the Roman Curia and my family, nurturing little exchanges of favors – no big deal in fact. In 1895, my great-great-grandmother Caterina, recently widowed, wrote to His Holiness Pope Leo XIII begging him to absolve her and her grown children – who she claimed were in poor health – from the observance of fasting and abstinence during Lent. Naturally, she promised, the dispensation would only apply to her immediate family – her servants would continue, under her supervision, to abide by the precepts of the Church; kept from eating meat, and fasting on the established days. The pontiff sent his decision via the local bishop who must have suspected chicanery because he did not grant the dispensation: so my carnivorous family continued to fast during Lent.

My trisnonna Caterina Pericoli (1835-1898)

The house at Collevalenza was a country property and none of its visitors expected to find the refinements of the city. The long cypress table was covered with thick and stiff linen cloths that smelled of lye and Marseilles soap, and was set with unpretentious crockery: glasses dulled by washing in ash, and our heavy unwieldy silverware. etched with the initials of distant ancestors. Someone in the house never failed to collect the first blossoms from the garden: branches of almond, forsythia, primrose and lilac were tucked without great artistry into a pot-bellied jug as a centerpiece. But the whiteness of the tablecloth, and the monogrammed napkins the size of bath towels, in that room of dark carved wood and gloomy walls; the fire in the eighteenth-century fireplace; the inviting fumes of each course; the clinking of cutlery against the edges of cream-colored plates; the chatter around the table, gave a festive and relaxed elegance that everyone – family member or not, monsignor or landowner – yearned for.

As long as my great-grandmother Sofia was alive, every meal included at least two courses of meat. If there was roast beef, chicken would follow; if there was meatloaf, there might be fried brains, tripe alla romana, jugged pheasant, hare, or whatnot. However Fridays – regardless of the month of the year – were observed strictly as lean days. And on St. Joseph’s Day, March 19 – my great-grandfather Giuseppe’s name day – the first artichokes would appear on Sofia’s table, the same which would have accompanied – fried or stewed – many Lenten lunches, together with cardoon parmigiana topped with sugo finto, omelettes, and sautéed wild herbs for which everyone in the family was crazy.

Baccalà alla perugina, queen of Lenten meals

Great-grandfather Giuseppe Bianchini in his regalia as Cameriere segreto di Cappa e Spada

It was on a meatless Friday that my grandfather Francesco planned to celebrate his engagement to my nonna Margherita. When the cook came to ask Sofia to dictate the luncheon menu, my bisnonna ordered codfish. With great embarrassment and a lot of tact, the woman protested that it would be indelicate to serve cod for such a special occasion – the only dish, she reminded Sofia, that Francesco could not stand. My great-grandmother had no idea: she never had suspected that he didn’t like cod; she had raised her only son so well! Indeed, the undisputed king of Lenten meals was codfish. You could buy it at the local grocery store of which there were two in Collevalenza, one just outside the town walls and the other inside, nicknamed Sereno (fair weather) and Brutto Tempo (bad weather). Aside from the meteorology that pitted the two against each other, the first also served as a haberdasher’s shop, while the second stocked hardware and stationery, and also sold its own meat – which is why we kept an open account there. For a few days the cod – white as ghosts – released acrid brackish odors in the pantry. Then the fish would be soaked and rinsed two or three times. In a house like ours, where there was an abundance of frying, I imagine that the cod was cut into fillets, floured, and fried before simmering in a pan with sugo finto in which a handful of raisins or prunes were always thrown. For me it was miraculous that dried up and pestilential fish like cod could be transformed into soft and crispy morsels, bathed in a delicious savory sauce, and decorated with a sprinkle of freshly chopped parsley.

The walls of Collevalenza

For us children, dispensed from the orthodoxy of our elders to fasting and abstinence, meat or no meat for lunch made little difference. Make a little sacrifice, the adults told us. Give up a delicacy; your television shows, a superfluous purchase. With so much good food in the pantry, and in the cellars of the house, Lent put my good intentions to a harsh test. My craving for dry sausages crept into my mind with greater insistence, especially on Fridays; I was told that the devil tempts most when the sacrifice is hardest. I used to steal into the cold cuts room where necklaces of sausages festooned the ceiling, just to inhale the smell. With the knife that hung on a string from the ceiling, I’d cut the thread, and with a twist detach a sausage from the casing that held it in line with the others. The skin came off effortlessly and hovered impalpably in the air, leaving the lumpy pinkish-brown sausage naked, and ready to be bitten.