BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

On September 22, 1927, more than 120,000 people had thronged into Soldier Field, Chicago, for what was billed as the second Battle of the Century. It was the fifth and last million-dollar gate in boxing history.

At Soldier Field.

For Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey, their careers were at stake, a world championship to be won—it was a chance for Tunney to beat Dempsey for the second time in less than a year:

During the week, trains pulling private and Pullman cars had converged on Chicago, carrying Hollywood entertainers, European royalty, bankers, industrialists and politicians, greats and near greats, sports fans, czars of the underworld, the son of the Duke of Marlborough who came by private rail coach with Harold Vanderbilt, and Princess Xenia of Greece.

By 4 pm, six hours before the fight, tens of thousands of people swarmed across Michigan Avenue, making it almost impossible to walk the sidewalks of the Loop. Grant Park had been cleared of people and 6,000 police set up a cordon four blocks from the arena. More than 50 million people, the largest broadcast audience ever, tuned into their radios.

—Excerpt from The Prizefighter and the Playwright Gene Tunney and Bernard Shaw by Chicagoan Jay R Tunney.

More than 1,200 journalists from around the world gathered to capture the spectacle, including Grantland Rice, who wrote: “Never again will I witness the mass that jammed soldiers field.”

Gene Tunney in the crowd.

Later, a reporter for The Chicago Herald and Examiner would write that Mrs. Vincent Astor was shouting at ringside and Mrs. Samuel Insull “kept her handkerchief in her mouth, she couldn’t have stood much more.”

In a chapter titled “The Long Count,” so named because Dempsey didn’t go to his corner when Tunney was down and thus delayed the referee’s count, Jay Tunney captured the evening’s unmatched drama. Nicknamed The Fighting Marine, Gene Tunney defeated Jack Dempsey for the second time that night in Chicago and retired, undefeated, in 1928.

The fight.

Gloves on.

Jay, his father’s youngest son, wrote that his father was almost late to his Chicago rematch with Dempsey: “In an upstairs bedroom of a house in downtown Chicago, the heavy weight champion lay stretched out on the bed for an hour and a half, slowly reading the last two chapters of Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, a novel that explores the intellectual and emotional development of an orphan raised by a pious son.”

His victory over the French prizefighter Georges Carpentier in 1924 had captured the attention of George Bernard Shaw, who loved boxing as well as heroes like T.E. Lawrence, known in film as Lawrence of Arabia. Tunney’s love of literature, and his wish to star in a play based on Shaw’s Cashel Byron’s Profession, about a world champion Irish prizefighter, is a theme throughout the book.

A Near North resident, Jay is working with a local playwright in hopes to soon turn his book into a play, and with his filmmaker daughter, Teressa, to create a documentary film series. Teressa, a graduate of Columbia University Film School, whose thesis filmed premiered at Cannes, began her career in Hollywood as third lead the wildly popular film Dude, Where’s my Car? with Ashton Kutcher, Jennifer Garner, and Fabio.

Jay Tunney.

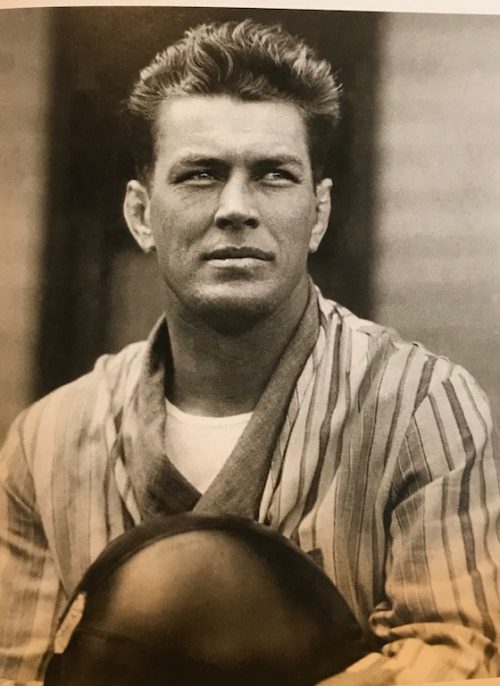

Gene Tunney.

Meeting Jay for tea at the Peninsula I was caught right away by his striking resemblance to his father, whom he cordially brought to life that rainy April day. I learned more about the golden age of boxing, 1900 to 1930, when it was everyone’s favorite sport. My own father held Gene on his list of revered public figures. Jay told me that a copy of the million-dollar check Gene received for the Dempsey rematch hung for many years in the Tunney garage, next to his car.

Teressa, Jay, Kelly, and Elizabeth and Jonathan Tunney, with children.

Jay and his wife, Kelly, moved to Chicago five years ago to be close to son Jonathan, his wife, Elizabeth, and their two children, his beloved granddaughters. He is the only surviving child of Polly and Gene—his brother, John Tunney, a US Senator and environmentalist from California, died last year.

A Stanford graduate, Jay became an entrepreneur in Asia, where he searched for oil in Burma, was a ship owner in Hong Kong, spent 10 years as founder and operator of the first premium ice cream chain in South Korea, and invented the Kimchiburger, an American beef patty spiced with Kimchi, Korea’s national dish.

“Gene Tunney was also a businessman, an investor in numerous enterprises from coal production to banking, and I know he would have related to my ventures. He was a self-made man with a driving iron will and the determination to better himself—attended by the fear of humiliation should he fail. That’s what Koreans are like, unstoppable,” Jay wrote of bringing ice cream to South Korea.

Taking 10 years to write his book, Jay has lectured around the world on the long-lasting friendship between his father and Shaw, both legends in their respective fields. Jay has been a member of the Governor’s Council of the Shaw Festival in Ontario and organized international Shaw conferences.

“Dad had started life as a poor Irish boxer from the Hell’s Kitchen, then a part of Greenwich Village, and he was desperate to become respectable. In those days, people quoted the great classics of Shakespeare, Shaw, Lord Byron, Keats, Shelley and Yeats. Dad really got into it. He was invited to lecture at Yale. He spent much time with the writer Thornton Wilder. At night he would listen to the music of Enrico Caruso and by day he was determined to make himself into a learned man. Dad was an extreme example of a person wanting to better himself, to have more in life than he had at the beginning. His own father died young, a longshoreman with many unresolved anger issues,” he shared.

“He married my mother Polly Lauder, who was a niece of Andrew Carnegie and grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut. They were married for 50 years. Although she was very tender, soft spoken, and loved poetry, the secret was that she wanted to marry a warrior not just some lawyer that her parents expected her to marry.”

Polly and Gene Tunney.

Jay told us more about the Long Count: “It had only been in boxing’s recent history that a law was introduced that a fighter had to go to his own corner when his opponent was down. Dempsey stood over Dad when he was knocked in the seventh round, and told the referee: ‘I stay.’

He added, “The fact that my father was so well conditioned, that he made his legs so strong by running five miles backwards every day, saved the day. He won the world championship, and the million-dollar prize, because he was quicker and faster and more intellectual than any fighter. Many gave him no credit. They said the reading made him a poser and men said he was too good looking for his own good. Dad felt very humiliated by the sports writers who influenced the fans, he never got over it. But he did set the finest record in boxing history.

Jay thinks now is the time to strengthen the importance of Shaw here in Chicago. Although he never met the writer, he did meet Ernest Hemingway and knew many of his father’s favorite friends: “With the death of Bob Scogin, Artistic Director of the ShawChicago Theater Company, in October and the announcement of the closing of ShawChicago which will occur in June, there will be a great gap left in Chicago’s cultural field. By creating a play about Shaw and my father, I hope to bring back that love of Shaw here,” he says.

“When Shaw came to London from Ireland at age 20, he looked like a timid little rabbit, but he went on to become England’s greatest orator and playwright. He loved boxing and he loved winners. He believed that no matter what your obstacles, if you tried harder and harder, your own willpower could overcome them.”

Tunney and Shaw.

“Shaw was one of the great lessons for Dad. Dad had an encyclopedic mind, and he worshipped what Shaw, who was 41 years older, had made of himself. Many years later, in 1950, along with friends William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, Gertrude Lawrence, Upton Sinclair, and Albert Einstein,” Jay explained. ” Tunney would help establish the first US Shaw Society. They would meet periodically in London, Europe, and Jerusalem after they first vacationed together with their wives in Brioni, the largest island in an archipelago in the northern Adriatic.”

He continued, “The spot was chosen partially to avoid reporters that followed him. It was said that even Charles Lindbergh didn’t have the number of fans following him that Gene did. They married at a hotel in Italy, Polly in a dress styled after Marguerite’s dress in Charles Gounod’s romantic opera Faust.”

“From the early 1900s until the 1930s, the island of Brioni was where all the titled English and Europeans went for vacation. I visited it five times as I researched my book. It has with a beautiful dry climate, much like San Diego. A vaccination for mosquito bites had been discovered there and it was thought to be a very salubrious place.”

In conversation with Shaw.

On Brioni.

Sporting games with Shaw.

Shaw and the Champ walked for days along the shore. The vacation was cut short when Polly suffered a ruptured appendix and severe infection. Two German doctors were called to the island and operated on her on the kitchen table.

Although Tunney didn’t encourage his children to box, physical fitness was key. But most of all, he wanted them to be well read: “He felt it was important that we learned the value of literature, poetry, and the humanities. We received nickels and quarters for what we memorized.”

The dapper couple.

Gene Tunney died at age 81 in Greenwich in 1978. Before her death in 2008, just 12 days before her 101st birthday, Polly encouraged Jay to continue to write the book about his father and Shaw. She shared many memories although she remained a quintessentially private person. She told her son: “GBS really was Dad’s spiritual leader. Maybe, the only father figure he ever had. He was closer to Dad than anyone else ever was again.”

Polly Lauder Tunney.

Tunney and Polly had loved to read poetry together, and the opening lines of John Keats’s poem Endymion, which she read to him in the early days of their courtship and marriage, are written on her tombstone:

A thing of Beauty is a joy forever.

For more information, visit tunney-shaw.com.