By Brigitte Treumann

I consider Istanbul the queen of cities. A bold statement indeed, considering how many other spectacular, exciting, beautiful cities exist on our globe. But among the many that I have been lucky enough to visit or have lived in, Istanbul occupies a special place in my heart and mind. It was love at first sight when, on a first trip, the taxi took my daughter Julie and me from the airport to our hotel with a wide view of the Marmara Sea. Happily, I was able to return several more times, to stroll with dear friends, Andy Austin and Ted Cohen, to wander about by myself, to have long chats and lots of hot apple tea with my favorite rug dealer Murat in the Grand Bazaar. Each time I discovered yet another elegant mosque by the master-builder Sinan, romantic parks where leisurely older denizens meet, seated around a fountain and a pool lined with cleverly designed mosaics, and each time I was deeply struck by Istanbul’s incomparable geography. The formidable triad of great bodies of water, the Sea of Marmara, the Golden Horn and the Bosporus, that separate and unite the vast and very different neighborhoods, quartiers, and parts of this ever-growing metropolis. As a historian and archaeologist, a sleuth of the past, a mistress of historical memory, I also felt deeply drawn to this “place” where both past and present are so intricately and visibly connected.

Maybe somewhat like Rome — there is, of course, an intimate historical relationship — the many layers of the city’s history are overt and apparent — you sort of stumble on them — from the Byzantine (and earlier the Eastern Roman Empire) Empire, 1204, 1261- 1453, the Latin Empire (1204-1261), the Ottoman Empire (1453-1922) and the Republic of Turkey (1923 -Present). Each epoch left (and leaves) indelible and tangible imprints. I walked along the Theodosian Walls (AD 412-422), I beheld the imperial column of Constantine I in the Hippodrome in the Sultanahmet District, where two of the city’s most significant monuments face each other across a park and gardens: The Blue Mosque and the Hagia Sophia. The Hagia Sophia, built by Emperor Justinian in 537 AD as his most important, triumphalist monumental church, the crown, the paradise on earth of Byzantine belief, has most recently captured international attention. After much negotiation, conferences, diplomatic considerations and popular acclaim, the ancient building has once again become a mosque. It had been once before when, with the advent of the Ottomans in 1453, the Byzantine Hagia Sofia church was turned into a mosque. President Kemal Ataturk in the 1920s, as part of his secularizing the new republic, declared this iconic building to become a museum to which everyone, all nations, regardless of their religious persuasion would have access. In many ways, Aya Sofia symbolizes the deep strata of Istanbul’s long history, its constant changes, its past and present, and future.

My essay today does not intend to recount the facts of a long history or discuss the well-known and deserving- of- fame monuments and sights of Istanbul, but rather present select images and their contexts of day-to-day impressions of my last visit which lasted just a few days. It was memorable and afforded me the feeling of not just being a tourist. Walking with my camera whither the spirit and my energy would take me. As a side note, it is far easier to travel alone when you also wish to do some serious photography.

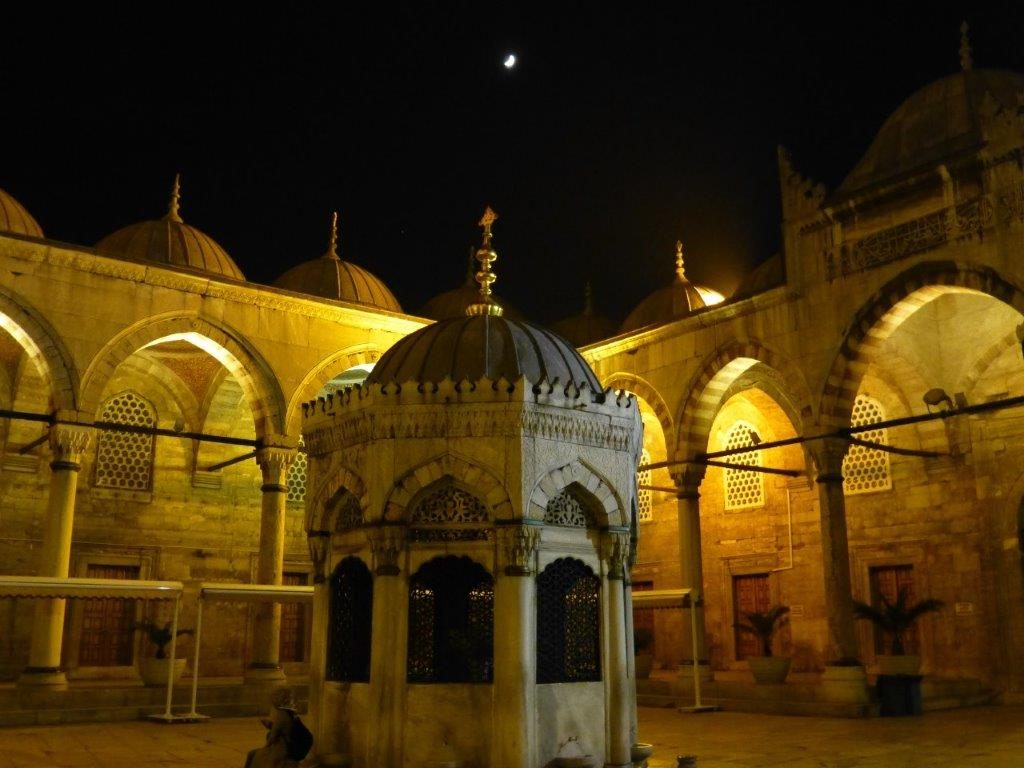

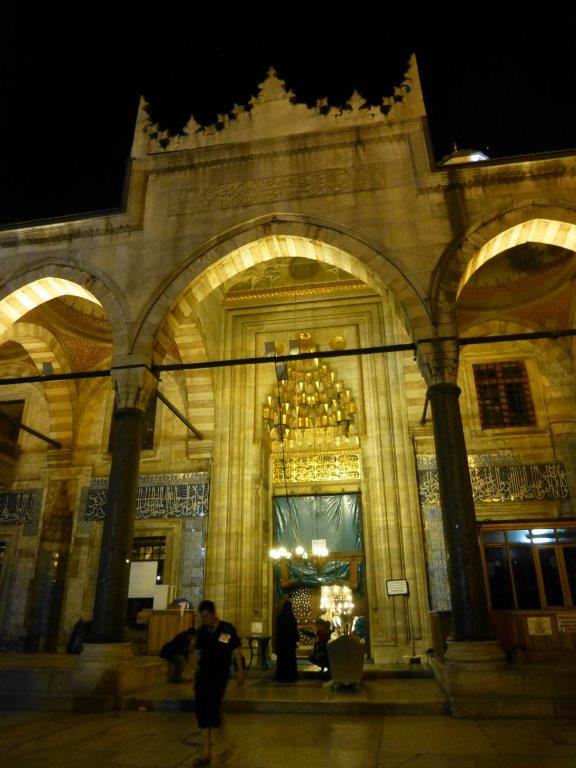

One of my favorite image moments was standing in the port of Eminonu late one evening, near the landing of the commuter boats that take people from the European to the Asian shore of the Maramara, or up the Bosporus. I write in my diary: “the blue bridge in the far distance, lit up Galata Kulesi (Tower of Galata) across the Golden Horn, brilliant minarets, the slow-moving ferry ready to take on last-minute commuters. Nearby on the waterfront the superbly beautiful 17th-century Yeni Cami (New Mosque) in its nightly splendor.

On a sunny morning, I wound my way through ancient streets in the Sultanahmet neighborhood and came upon a restful, charming park, the Kadirga Meidan. A lively fountain set in a pool lined with beautiful blue mosaics and a clever design depicting an Ottoman sailboat shimmering through the water. Seated on comfortable benches were leisurely older denizen deep in conversation. I also took a break and sat under a sweet-smelling jasmine tree. I nodded off leaning on my backpack and woke to the kindest smile of a chador-clad woman who had obviously watched over me. I think about her and her smile, a good omen. All rested I wandered through this non-touristy part of Sultanahmet where you can still find those charming wooden houses, called konak, so typical of old Istanbul. Increasingly they are replaced by modern not so charming, but more comfortable dwellings. The elegant interior of a smaller neighborhood cami (mosque) made my day.

Sometimes, wandering through the older Istanbul neighborhoods, one comes across a Sufi dervish doing what is called “the turn”. That would be the proper word, not “whirling” as most westerners think of it. Sufi groups do perform the whirling ceremony internationally as a show – something I don’t like – it’s a form of spiritual meditation and mainly practiced by the adherents of the Mevlevi order, founded by the great 13th-century Persian poet and Sufi mystic, Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi.

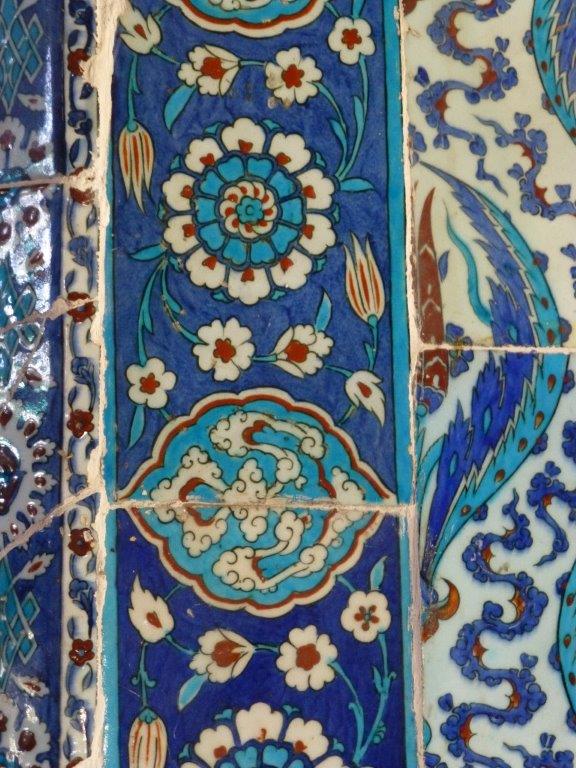

There are innumerable mosques of all sizes, styles, and periods throughout Istanbul. One of the greatest, if not the greatest Ottoman architect, Mimar Sinan ca. 1488 – 1588, built many magnificent camis, the most famous of nearly overwhelming dimension is the Suleymaniye Mosque, a memorial to its founder Suleyman the Magnificent. On this last trip, I decided to visit some of Sinan’s smaller, brilliant, more intimate camis, the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha cami near my perfect apartment in Sultanahmet, and the incomparable Rustem Pasha cami close to the Spice Bazaar. Most of its interior is covered in Iznik tiles. (The town of Iznik was the most important producer of decorated tiles and vessels in the 16th-century). Standing among all this beauty made me nearly swoon.

In conclusion, I ought to mention how fortunate I was to find an apartment in that great neighborhood of Sultanahmet. My convivial landlord of three days, Musa, made the stay a happy experience. Musa is a well-known weaver of silk kilims in extraordinary colors that he extracts from a great variety of plants. It was most entertaining to watch him dump whole bouquets of dried lavender and indigo into a big old pot of boiling water. But the best aspect was the view from my tiny balcony over green arbors, the Sokullu Mehmet Pasha cami to the glittering blue Marmara Sea. My last picture on that trip is a nocturnal view from Musa’s balcony.

I plan to return as soon as we shall be able to travel again.