BY LENORE MACDONALD

Our year: 1898, autumn.

Our setting: The “old” road from Denver to Santa Fe on a deserted, spectacular stretch of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, just north of Taos.

Our Protagonists: Two Easterners, artists Ernest Blumenschein and Bert Phillips, who studied at the Arts Students League in New York and at the Académie Julian in Paris.

The Rest Is History: Our protagonists, Messrs. Blumenschein and Phillips, were on a sketching trip from Denver to Mexico.

Ernest L. Blumenschein, The Burro, 1929, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Henry Ward Ranger through the National Academy of Design, 1975.85.

Just north of Taos (near San Cristobal where heiress Mable Dodge Lujan would later give a ranch to D.H. Lawrence), our intrepid artists got the modern equivalent of a flat tire—their surrey wagon slipped into a deep rut on that mountainous road and the wheel broke. Blumenschein left Phillips behind and went to Taos, the nearest civilized spot, with the broken wheel. What they saw during their respective wheel repair mission and while waiting astounded them.

The broken wagon wheel that started it all.

Eureka! They had found exactly what they were looking for: that incredible light, an endless horizon with its blue skies, captivating clouds, stunning sunsets, the majestic, mysterious mountains, the rolling, frolicking Rio Grande, and picturesque Native and Hispanic cultures. Phillips settled in Taos, but Blumenschein returned east. Phillips said to Blumenschein, “For heaven’s sake, tell people what we have found! Send some artists out here. There is a lifetime’s work for twenty men.”

Indeed, there was more than a lifetime’s work for more than twenty men—and women.

Phillips was to remain in Taos permanently. Blumenschein lived on and off in Taos for the next 20 years, while also spending time out East and in Paris.

Eanger Irving Couse, Elk-Foot of the Taos Tribe, 1909, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans, 1910.9.5.

Saginaw-born Eanger Irving Couse was their first convert, arriving in 1902 via The Art Institute of Chicago, the National Academy of Design in New York, and Académie Julian. He had also lived in Étaples, an art colony in Northern France. Although he established a winter studio in New York, he returned to Taos every summer and it became his year-round residence in 1928.

Over the next several years, the three would be joined by Henry Sharp, Oscar Berninghaus, Herbert Dunton, Julius Rolshoven, Walter Ufer, Victor Higgins, Martin Hennings, Kenneth Adams, and Catherine Critcher. Again, all were professional artists from the East with very promising careers.

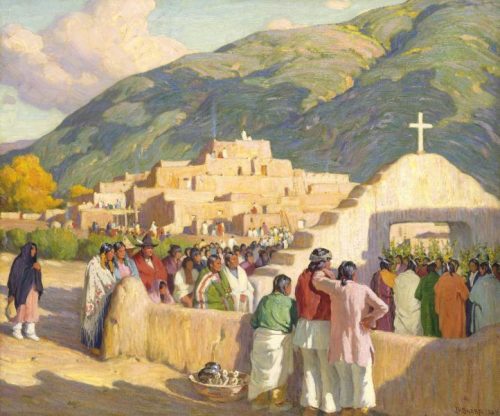

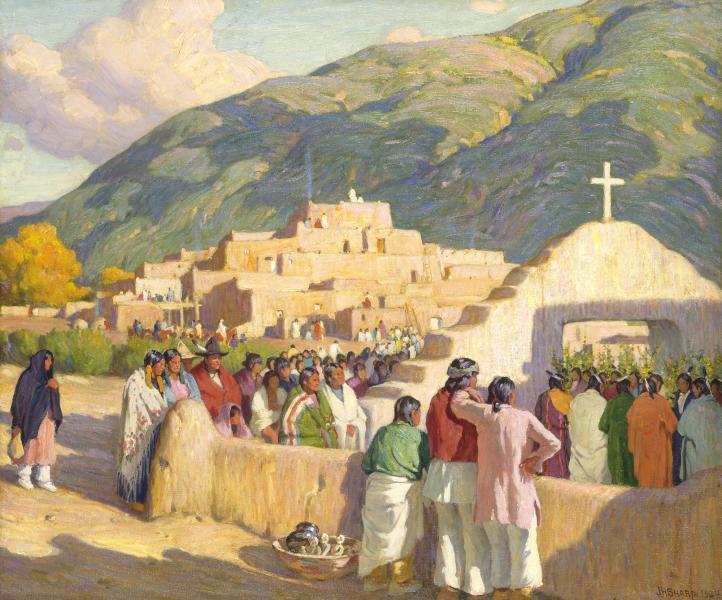

Joseph Henry Sharp, Sunset Dance – Ceremony to the Evening Sun, 1924, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Arvin Gottlieb, 1991.205.15.

Those 12 artists formed The Taos Society of Artists (the TSA), the first of many New Mexico art societies and impetus, for example, for Will Shuster, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, Jozef Bakos, and Willard Nash to form Los Cinco Pinteros in Santa Fe around 1921.

Couse helped organized the TSA, was its first president, and tirelessly promoted this fledging artists’ community, “sending circuit exhibitions across the country and exposing their audiences to new culture, new visions, and a new landscape,” according to Davison Packard Koenig, Executive Director and Curator of The Couse-Sharp Historic Site and Lunder Research Center.

The Taos art community expanded rapidly from the 12 members of the TSA, attracting later artists like Andrew Dasburg, Emil Bistram, Gene Kloss, and others who would later be known as Taos Moderns. This put Taos “on the map for art and tourism, making it one of the most important art colonies in America,” said Koenig, and encouraged many artists and tourists to experience New Mexico where light, landscape, and culture are among the most captivating on earth.

And it all started with a broken wagon wheel on a mountain road north of Taos.

***

For more information about The Taos Society of Artists, Couse-Sharp, the Hardwood Museum, and the Taos Historic Museums are all great resources, as is this article from the Santa Fe New Mexican.

The homes and studios of Ernest Blumenschein, E.I. Couse and Joseph Sharp in Taos are open to the public.

© 2019 Lenore Macdonald All rights reserved.