By Judy Carmack Bross

The Art Institute’s Gloria Groom shares with guests at the June 8 Alliance Francaise of Chicago Symposium the influences on artists and writers made by Paul Cezanne, the featured artist for the museum’s blockbuster summer exhibition, attracting visitors from around the world. The final lecture of the highly popular Symposium on the Arts of France focusing on three centuries of artistic influencers will be held at the Alliance and is open to the public.

To Groom, co-curator of the exhibition and Chair of Painting and Sculpture of Europe at the Art Institute, will show Cezanne’s art as the bridge between the vanguard of his own time to artists of the next generations, who were liberated by his radical new approach to making art.

Paul Cezanne. Madame Cezanne in a Yellow Chair, 1888–90. The Art Institute of Chicago, Wilson L. Mead Fund. |

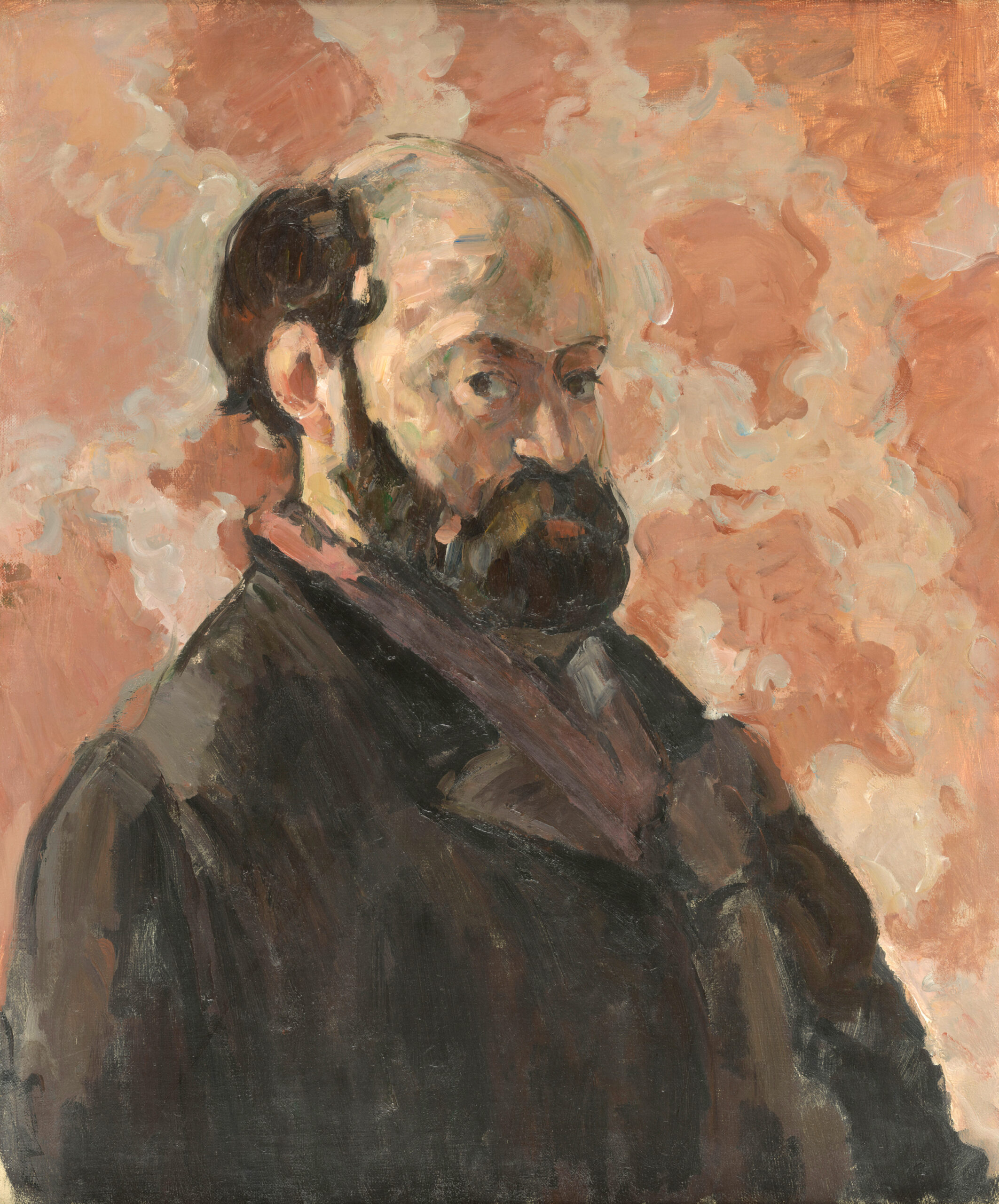

Paul Cezanne. Portrait of the Artist with Pink Background, about 1875. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, donation de M. Philippe Meyer, 2000. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Adrien Didierjean. |

“Cezanne was definitely the bridge to the twentieth century. Picasso and Matisse felt his liberating approach for nudes and landscapes as well as the way he used paint on canvas,” Groom said. “He was the odd man out with the Impressionists, although he was friends with Pissarro and Monet in particular. For him every stroke mattered, and had to communicate what he referred to as his sensation, the emotion, the feeling that he had at that moment inspired by that object or person.”

The first major retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States in more than 25 years and the first exhibition on Cezanne organized by the Art Institute of Chicago in more than 70 years, it was planned in coordination with Tate Modern, the show contains 80 oil paintings, 40 watercolors and drawings and two sketchbooks. Groom curated the exhibition with Caitlin Haskell, Gary C. and Frances Comer Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art and the Tate Modern’s Natalia Sidlina, Curator, International Art.

Paul Cezanne. The Bay of Marseille, Seen from L’Estaque, about 1885. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection.

“Normally my work is in the nineteenth century, and Caitlin Haskell, who has long studied Cezanne, has helped me to understand how much he matters,” Groom said. “Because of COVID, our Monet show last summer was really directed to a Chicago audience. This is our first exhibition in nearly four years that people can travel to see. I am hearing many different languages spoken as I visit the exhibit.

“Cezanne was definitely an influencer among other artists. He was an artists’ artist. His contemporaries might have been puzzled by his work but they were very aware of it. He was obviously very much a risk-taker, although not experimental with materials and even subjects, like Degas, for example. Cezanne developed a new form and approach to standard subjects. There was not the settled look that one sees in still lifes by other artists. His are lush, appealing impossibly balanced. He found a new form and approach to traditional subjects.”

Paul Cezanne. Still Life with Apples, 1893–94. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. |

Paul Cezanne. The Basket of Apples, about 1893. The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection. |

A year after Cezanne’s death when a memorial exhibition of his work appeared at the Salon d’Automme in Paris, the German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker wrote that “one of three or four artists who have affected me like a thunderstorm, like some great event.” Even those artists more devoted to traditions and conventions of European painting admired what Cezanne for establishing tenets for modern painting as the nineteenth century ended.

His works were owned by his contemporaries including Picasso, who bought a painting of Montagne Sainte-Victoire to be “closer to his “spiritual ancestor”, and Claude Monet who collected the largest number of Cezannes, called him “the greatest of us all”. Camille Pissarro, with whom Cezanne often painted in the 1870s was forever an admirer.

Paul Cezanne. The Eternal Feminine, about 1877. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Many other artists continued to collect him including Jasper Johns.

At the second Alliance Symposium, Northwestern professor and scholar Alicia Caticha described the fashion influence of two eighteenth French artists, Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun and Adelaide Labille Guiard.

Paul Cezanne. Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), about 1894–1905. The National Gallery, London, purchased with a special grant and the aid of the Max Rayne Foundation, 1964.

“Cezanne was definitely not a fashion influencer but he can be found in literature of the time,” Groom said. “To Zola, he becomes like an avatar, an embodiment of the misunderstood artist, so different from others, and so appealing in that way. In several books you see Cezanne personified as the person who refuses to conform.”

To Groom, it was important to include Cezanne’s early work.

“He chose simple subjects like still lifes, a laborer at his home in Aix, Mont. Sainte-Victoire. The exhibition encompasses the range of Cezanne’s signature subjects and series from landscapes, lesser-known allegorical paintings, bather scenes, portraits and rarely seen works from public and private collections in North and South America, Europe, Australia, and Asia.

Paul Cezanne. Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, about 1887. The Courtauld Gallery, London. © Courtauld Gallery / Bridgeman Images. |

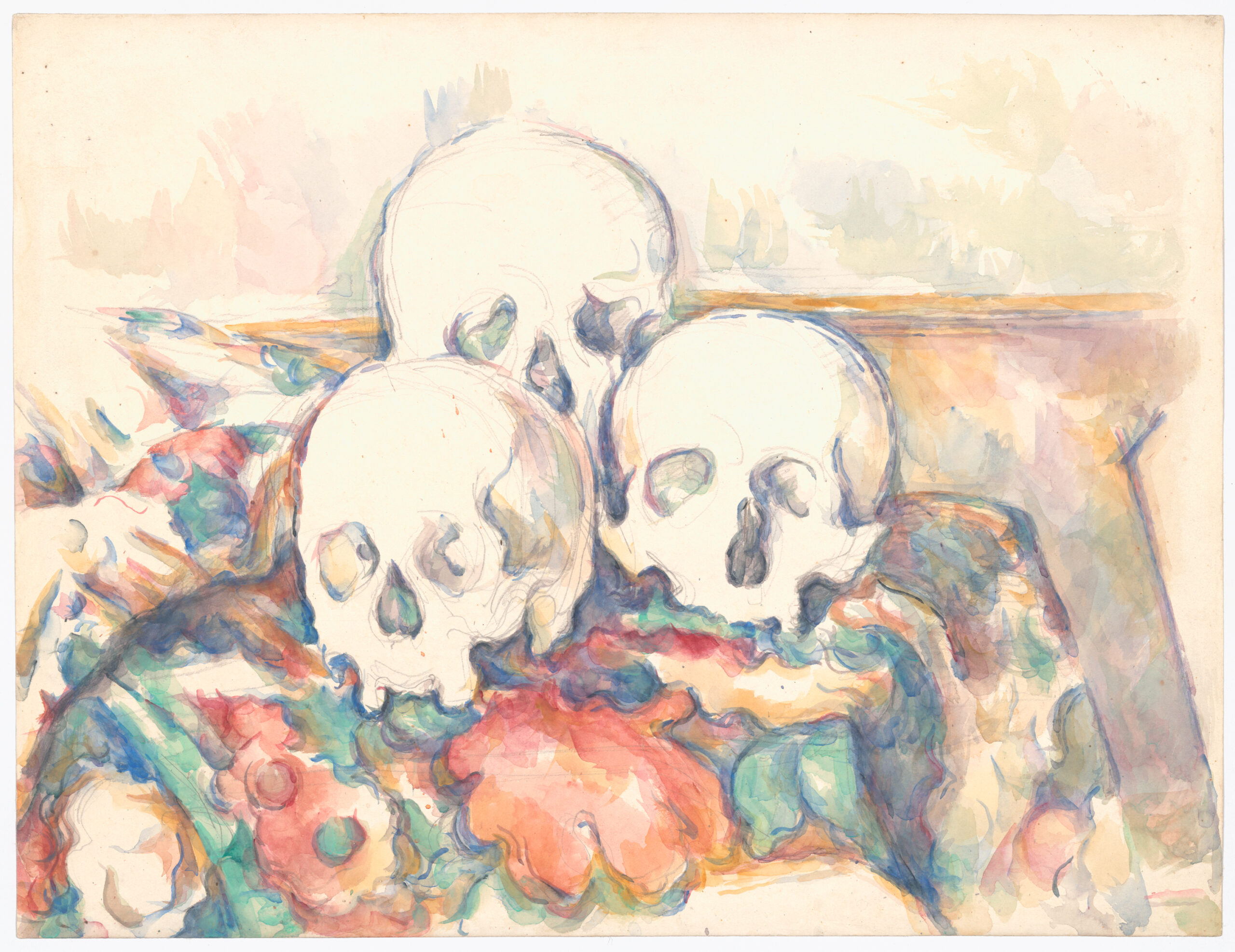

Paul Cezanne. The Three Skulls, 1902–6. The Art Institute of Chicago, Olivia Shaler Swan Memorial Collection. |

For more information about Gloria Groom’s presentation at the Alliance Francaise June 8, visit af-chicago.org

For more information about Cezanne, running through September 5, at the Art Institute of Chicago, visit artic.edu