By Francesco Bianchini

Artichokes – a name not especially impressive for vegetables as attractive as flowers and as succulent as few others – appear at produce stands when winter is still dragging on.

Plump Roman artichokes stewed and seasoned with garlic and mint were mistakenly called ‘Jewish style’ in my family. Someone occasionally objected, attempting to correct our lingo, but custom prevailed – my misunderstanding continued until, as an adult, I lunched in Rome near the Portico d’Ottavia and ordered a real artichoke – alla giudìa – fried whole and resting on its folded napkins like a sprawling peony.

…like a sprawling peony…’

Perhaps a singular figure of my grandparents’ war-time household should have cleared up the mistake: a gentleman well into his sixties who openly came to stay in the house as a friend of a great uncle, with the understanding that he needed ‘quiet time’ to recover from a debilitating illness, and to attend to some scholarly pursuits. My grandmothers Anna and Margherita alone knew the truth: no one else suspected a member of the prominent Jewish Sraffa family, hiding out from the Fascist racial law in sleepy Collevalenza.

Nonna Anna with my mother (right) and her siblings also during the war

In the rambling family home Sraffa occupied the room later inhabited by a distant aunt. He joined family dinners, ate the last stewed artichokes of the crop with gusto, enchanting everyone with his urbanity and culture. To perpetuate the pretence, he never missed the Marian cycle of Masses, every evening in May, sitting among the family in the choir loft of the parish church, accessible exclusively to us across what we children later dubbed our own ‘bridge of sighs’.

The villagers became accustomed to the distinguished and devout figure, ultimately taking him for a family member from a lesser known offshoot. Throughout his stay Sraffa was well camouflaged by the devotions of the women of our house, by the monsignor’s frequent visits, and by our steady Umbrian diet – often including pork. Sadly the man’s heart gave out before war’s end, and nonna Anna’s dutiful vigil culminated – to protect the family – with a summons for the priest who administered Last Rites.

There was daring too in hiding a pair of downed RAF airmen in our attic, a sentimental initiative certainly taken by grandmother Anna who’d met her French husband in 1920s London while volunteering as a nurse. One wonders at the coordination needed to take care of the men by one or two trustworthy servants, without anyone else noticing anything – the secret kept especially from my great-grandfather who was elderly and ailing. Few were aware of the purpose of the constant comings and goings of the forty-year-old sisters-in-law – Anna, her small black-gloved hands and hat askew, and Margherita, forgetful of herself after the loss of her young husband, with shoes often mismatched.

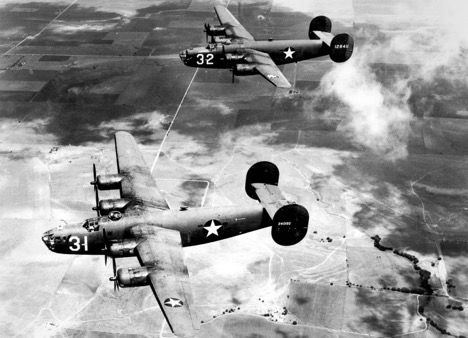

Mamma, then a child, and her sister and cousins trekked to the convent of Montesanto, just outside Todi, where the friars repaid the family for its charities by filling their satchels with every good thing from the monastic garden. For mamma these unsupervised outings were adventures, but the older girls resented being seen, perhaps by their classmates, returning with leeks, chard, and celery protruding from their loaded bags, and insisted that they follow a circuitous route taking advantage of the siesta time. It was on one of these sorties that allied planes flew low overhead to bomb the ancient bridge over the Tiber. In Todi my father – a boy of seven or eight – watched from a roof as the planes aimed at the train station at the foot of the hill. (‘Much better than fireworks!’)

American bombers over Italy, 1943

For my parents as children the war was a long, strange, and suspended time, yet unaffected by personal trauma. At the outbreak, my mother’s French family hadn’t been able to return home. My grandfather Alexis remained on the other side of the Alps in ‘hostile’ territory. He would have to wait until the end of the madness to embrace them again. By themselves the mother, two sisters, and one brother led a normal life in Italy, not needing to hide their surnames which were, after all, those of the ‘enemy’. In my great-grandfather’s house in Rome, the grown-ups pointed with grave faces at a large map of Europe, but when the family moved to Todi – a hospital town and therefore thought safer – the war years faded into surreal, borderless, everyday life. The only way to keep up with events was to listen in secret to BBC radio.

The hilltop town of Todi, protected somewhat by the presence of a hospital

The few men of the household escaped the horrors of the first world war because they were too young – and they were all already too old for the second. There was a scarcity of certain goods – antique parchment used instead of toilet paper – but never a shortage of food. The children were not made aware of what was going on, or of the risks that adults were taking. Thus, my grandmother Margherita’s Fiat Balilla laid buried under the firewood, the logs constantly renewed so that the Nazis (who briefly requisitioned the house in Collevalenza) would not find it. Nor did they guess of the family silver secreted in a cubby hole, hidden behind a painting.

Nonna Margherita with my father and sisters in 1942

Then came September 8, 1943; the war for Italy was over but the worst then ensued. Anna, reading Gone with the Wind, lived those moments in symbiosis with Scarlett O’Hara fleeing besieged and sacked Atlanta when she saw people in the streets toting stacks of hats and looted shoes. She wished she’d had Melania’s guts to arm herself with her father’s ceremonial sword when a Nazi soldier burst into the house and shot the lock off an eighteenth-century desk to pry it open.

The joyous liberation

The German officers (‘elegant and well-mannered’) were succeeded by American ones (‘big boys with photos in their pockets of the farm over there, and of their moms smiling next to an apple pie’.) The latter arrived in jeeps and tanks and paused in the main square of Todi to give themselves a good scrub and shave, their basins of soapy water balanced on the bumpers. (‘The extravagance of leaving behind whole bars of real soap!’).