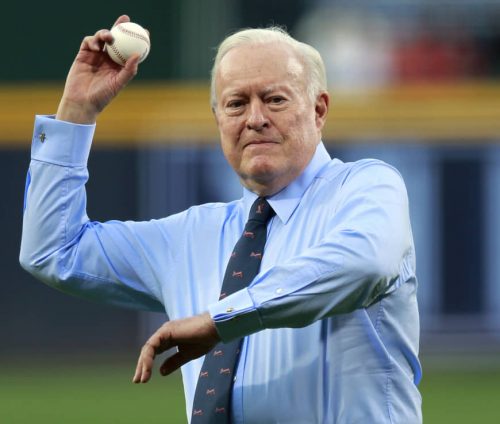

Bill Bartholomay Made a Major-League Impact on the Game He Loved

By David A. F. Sweet

As a young boy during The Great Depression, he met Major League Baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, at an estate in Wisconsin. A few years ago, he took in MLB’s first game in Australia, played on a cricket field. This February, he chatted with Atlanta Braves players at their new spring training facility in Florida.

The breadth of what Bill Bartholomay — who died at 91 on March 25 — experienced in baseball is practically unmatchable by anyone alive today. It seemed fitting he died the night before what was supposed to be Opening Day, often his favorite day of every year. Of course, this year it had been postponed to an unknown date. Why wait for that when he can get a game going up above?

Though Bartholomay served on the board of the Chicago White Sox for a spell, it was with the Braves he made his mark. He explained to me at lunch in Chicago how in 1962 — only seven years out of Lake Forest College — he and a group of investors made a play to buy the Milwaukee Braves, owned at the time by Lou Perini. Bartholomay headed to Massachusetts to visit Perini (the Braves were originally situated in Boston).

“I hung around his office for a couple of days,” Bartholomay told me. “The only person I stalked in my life was Mr. Perini. Finally, his secretary took pity on me.”

Their fruitful meeting and the $5.6 million purchase (the Braves today are estimated to be worth $1.7 billion) led to a couple of fun years in Milwaukee for the Winnetka native. Bartholomay would always invite Chicago-area friends to join him in the owner’s box at County Stadium in Milwaukee. Truth was, though, the Braves weren’t drawing well, and the County Stadium lease was poised to expire. When he announced the team was moving, Milwaukee fans were enraged — including future MLB Commissioner and Milwaukee native Bud Selig, who would bring baseball back to the city via the Brewers and become one of Bartholomay’s best friends.

Bill Bartholomay’s children — Karen L. Baldwin, William T. Bartholomay, Jamie B. Niemie, Ginny Bartholomay, Sally B. Downey and Betsy B. Benoit — gather around their father during his 90th birthday.

In 1966, Bartholomay relocated the Braves to Atlanta, the first Major League Baseball team to play in the Deep South. Every direction he looked, the market was his; no teams in Chicago or Minnesota to take away potential fans.

One decision he made there showed both his love for baseball history and appreciation of black players. He signed Satchel Paige, then in his 60s, to a contract so he could qualify for a Major League Baseball pension after more than a dozen teams refused Paige’s plea.

The Braves teams in Atlanta were generally middling that first decade, but for one moment they grabbed the attention of the world during an unheard-of event: a regular-season baseball game broadcast nationally at night. The nation was electrified when Hank Aaron smacked his 715th home run on April 8, 1974, topping Babe Ruth’s all-time record that was considered unbreakable.

“I was sitting in the front row with Hank’s mother and father,” Bartholomay told me. “There’s a place where you go beyond adrenaline — I carried his mother above the barrier and onto the field after he hit it.” The duo welcomed Aaron at home plate.

One of his daughters, Sally Downey, remembers how she and her siblings would think nothing of having dinner with Aaron near the Braves’ spring-training park in West Palm Beach.

“Our childhood spring breaks were magical, but none of us knew it at the

time,” she said. “We had the run of the motel where the Braves’ players were staying and thought nothing of playing Scrabble on the stairs with Rico Carty or waving at Joe Torre while we were swimming.

“As we grew up, we realized that Dad gave us a front-row seat to some of the best experiences in baseball. We have memories that will put smiles on our faces for a lifetime.”

Bill Bartholomay’s love of baseball never faded. It started in boyhood and lasted into his 90s.

While baseball was his passion, the gentlemanly Bartholomay — who sold the team in 1976 to Ted Turner and became its chairman — was a sports aficionado. He captained his North Shore Country Day School basketball team. An early investor in the Atlanta Chiefs, a pro soccer team in the 1960s who captured the first North American Soccer League title, he even brought soccer great Pele there for an exhibition. He was extremely proud Atlanta — which was not at all a sports town until he moved the Braves there — played host to the 1996 Olympics, stunning Athens, Greece, which assumed it would receive the nod to hold the 100th anniversary of the modern Games.

Many know him best as a superb backgammon player at private clubs and beyond — he once captured the Pro-Am Doubles Championship with two-time World Backgammon Champion Bill Robertie in the Bahamas. Regardless of the stakes, he competed ferociously until just before he died. Board in front of him, he preferred to dispense of all small talk. He loved being the first to get a piece off the table. Upon accepting the doubling cube, he often kissed it.

Phil Simborg, once the second-best backgammon player in the United States, rolled the dice with Bartholomay in Chicago many times.

“He loved to compete and he loved to win, but one of the things I admired most about him was that when he lost, he was always a good sport,” Simborg recalled. “Virtually every time he won, he apologized and said he just got lucky. And much of the time he knew that wasn’t true at all. He won because he outplayed a poorer player.”

The man was engaged and sharp even as he entered his 90s. Last fall, I ran a panel called Talking Baseball in Lake Forest that featured Bartholomay, Chicago Cubs Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg and Alan Nero. who was former Cub manager Joe Maddon’s agent and represented many others in the game.

Bill Bartholomay (left) joined Alan Nero and Ryne Sandberg during a baseball event in Lake Forest last fall.

Bartholomay arrived early, dressed crisply in a blue blazer and tie. We all ate hot dogs before the sold-out event. During the panel, he defended the increasing length of baseball games, picked Braves’ slugger Dale Murphy as the one player he thinks should be in the Hall of Fame who isn’t and shared story after story about his 60 years in the game. He had recently received the Commissioner’s Historic Achievement Award, also earned by the likes of Derek Jeter and Ken Griffey Jr. No doubt he will be elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame soon.

As I write this, to my right is a picture of Hank Aaron and me, taken when I served as the Braves’ bat boy at Wrigley Field in 1972 at age 9 (Bartholomay was the bat boy for the Cubs at the same age). Though the story goes that my parents won the bat boy job at auction, no doubt it was at the behest of the Braves’ owner. Thanks to him, two years later Aaron autographed the photo to me and added a personal note about hitting his 714th homer — which tied Ruth’s record — on my birthday.

For anyone who loves baseball, Bill Bartholomay’s life was the stuff of dreams. He will be deeply missed.

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.