By Francesco Bianchini

One of my memorable meals took place in the Sacred Convent of Assisi. It is while I was tracking down the Perkins collection – master Italian artists of the 14th through 16th centuries – that I met Father Pasquale Magro. An employee of the comune of Assisi gave me his name: speak with Father Magro; he is the curator of the library. I called the friar about visiting the collection, also hinting of my curiosity about the food Saint Francis and his confreres might have eaten. I wangled an appointment but was forced briefly to postpone. Speaking again on the phone, the friar sounded annoyed. ‘Now I will miss evensong. And listen,’ he said, mulling the new situation, ‘I’m not sure I’m the right person for you. I don’t care a fig for cuisine and cooking…oh, well, whatever…just come when you want!’

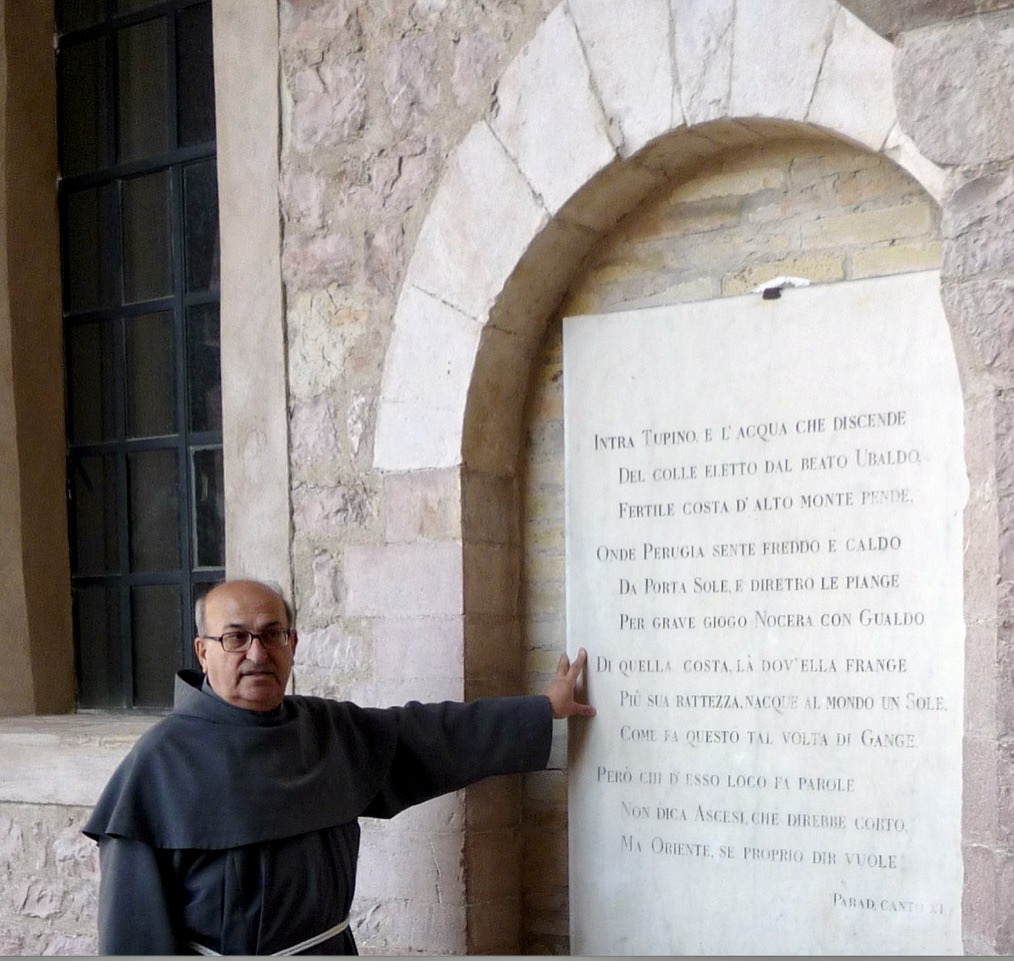

Father Magro, curator of the celebrated convent library

After the museum visit, Father Magro and I went out into the sunny cloister, just as the bells were ringing at the end of vespers. I apologized again for disrupting his schedule. ‘It’s not the end of the world,’ he said with a laugh, directing my attention to a young woman accompanied by one of the friars. She was wearing a strapless summer dress, so had been wrapped in a Franciscan hood and collar to cover her bare shoulders; now Little Black Riding Hood. We sat on a stone bench and conversed in the short time before the friar’s dinner. I took the opportunity to ask how the convent organized its meals, how they got their food. Father Magro chuckled. ‘St. Francis said Eat whatever is put in front of you. Some of us have tried abstinence and fasting, but our rules today have no limits except temperance. We have about forty friars and there are seven or eight local women who work in the kitchen, preparing meals, washing dishes, etc.’

‘Begging was the traditional way of getting food,’ Father Magro confided. ‘Unlike us, Benedictine monks don’t venture outside their walls, so they make and cook everything themselves. The same goes for Trappists, who are famous for their liquors and other specialties. We Franciscans, on the other hand, don’t have a penchant for cooking.’ ‘But what about those products that claim to be Franciscan,’ I inquired. ‘We have nothing to do with them,’ he cut me short. ‘The famous Amaro,’ he said with a grimace: ‘I tried it once. Aftershave!’

The setting for my lunch at the Sacro Convento of Assisi

I asked him what his culinary preferences were. ‘I am not difficult about food,’ he answered. ‘I’m Maltese and I don’t understand the Italian habit of talking about food all the time, as many here do, even at the table. I’m content with bread, some spicy cheese, and a glass of wine. What could be more essential?’ He paused to reflect. ‘After all, there is no Eucharist without bread and wine.’

When I mentioned Umbrian cuisine, he looked at me defiantly. ‘Chef Veronelli said Umbrian cuisine is the tomb of Italian cuisine and I agree. There aren’t many noteworthy dishes here, and certainly few wines – with the exception of Sagrantino di Montefalco, of course. Once some of our German brethren offered some bottles of Rhine wine and they disappeared in the blink of an eye. Sometimes we get good wines from Abruzzo, but the wine we usually drink is made by the Poor Clares, in their convent in Spello. He winked with an air of understanding. Very weak, even before being watered down. Good only for Mass.’

Father Magro looked around the courtyard before commenting again. ‘We eat no differently from the local peasant families: plates of pasta and rice twice per week. We have meat and fish, of course; vegetables, fruit, apples and peaches. Today, Saint Clare’s Day, we even have ice cream.’ Suddenly, he raised his hands and exclaimed: ‘Umbrian cooks don’t know how to make good risotto! No way! And rice pilaf? I don’t think they know what that is! There was a man who used to cook for us some time ago, a graduate of hotel school. He made crostini with various toppings as appetizers. But he left us for a restaurant that paid more. Now it’s the local women and the bursar who decide the menu. Leftovers make regular appearances: midday pasta shows up again in the evening, as in the best families, I suppose. The brothers call it the feast of the relics. When I know about one in advance, I go out to dinner. I met a woman the other day at the top of the clearing in front of the Basilica. She asked me, Father, don’t you smell something bad? You bet I do, I told her. With our convent cuisine, this Assisi restaurant fare, and McDonald’s nearby, what do you expect?’

Another thought struck him: ‘Umbrian bread isn’t as bad as they say. Do you know about the Salt War? Umbrians, under the yoke of the Pope, refused to pay the Papal tax on salt. And since then, they’ve made their bread without it. All the better: healthier for your blood pressure, perfect with salty foods.’ He chuckled. ‘You Umbrians really are an anticlerical people, aren’t you?’

Leaning on his hands, the friar rocked back and forth on the stone bench and with half-closed eyes scanned the wide expanse of pinkish stone, the arches of the cloister, the filigree gates, as if to find a distraction, a curious detail. ‘I told you about the wine,’ he said, shaking his head and rolling his eyes behind thick lenses. ‘We’d like to drink it chilled from time to time, but we don’t have such refinements. The fact is, that in this heat if it’s nice and cold, we drink more of it. That’s one of the tricks of our bursar who makes sure our wine is lukewarm. But we drink that any way – even worse, we water it down with ice.’

One of the inner courtyards seen through the wrought iron filigree of the gate

Father Magro recommended a restaurant across the street from the Basilica. I was early for dinner and the place was almost empty. Smiling when I mentioned the friar’s name, the waiter escorted me to a table overlooking the sloping plaza. I looked at the façade of the Basilica, adorned with its great rose window, and at the junction of streets and old stone walls in front of it – exactly the spot where, according to Father Magro and his ladyfriend, the capricious winds of Assisi mix together the fumes and vapors of all the kitchens around.

The spot where the capricious winds of Assisi mix together the fumes and vapors of all the kitchens around

My lunch with Father Magro at the Sacro Convento di Assisi was set for a Friday, a few days before Christmas. Under a purple sky, Assisi was dazzling, albeit swept by an icy north wind. The padre came to meet me at the gate. ‘Cold, huh?’ he asked by way of greeting, stroking his cheeks. ‘But,’ he grinned, ‘cold keeps our skin young and fresh!’ Beyond the Franciscan appreciation for every season and every climate, Father Magro’s words seemed usually to analyze things with amused detachment.

The massive Sacro Convento of Assisi stretches out under the blue summer sky

A bell rang somewhere just as we entered a huge white room where about forty friars were already gathered. White is an understatement, for white were the window wells and walls; white were the arches and vaulted ceilings; white were the rococo lintels and elegant moldings. It was as if we had entered an un-gilded version of a gallery at Schoenbrunn Palace in Vienna. Long narrow tables occupied half the room, covered in white wax-cloth and set for lunch. At one end of the vast space there towered a Christmas tree – a stylized, spiraling green cone garnished with large blue balls. Father Magro noticed my gaze: ‘So, you like our Hilton-style tree?’ Then scanning the diners, crowding together on just a few tables, he suggested we sit alone at an empty one. After standing for a brief prayer the assembly regained their seats with a cacophonous scraping of plastic and chrome. I couldn’t help tipping my plate: ordinary English pottery, white of course. ‘Our best tableware,’ the friar laughed as he leaned toward me, ‘for use when we have guests.’ He glanced around the room again, pointing out several of the brothers. Besides a dozen Italians, there was a friar from China, an Australian, an American, some French, some Slovenians – the only layman present that day was me.

As it was Friday, lunch would be a lean affair, the friar warned. First to appear were large stainless steel bowls of mussels alla marinara. The freshly steamed mussels made one think of praying hands, lustrous with olive oil, floating in a lukewarm broth of oil, water, garlic, and chili flakes. The mussels were small, huddled inside their shells, perhaps shivering from the long journey from the kitchen. ‘A fisherman from the Marche gives them to us,’ reported the father, heaping some on my plate and serving himself. ‘We maintain the Franciscan tradition of begging, and most of what we eat is donated by those who might otherwise throw whatever into the trash can.’ I was interested to see and try the long-awaited wine produced by the Poor Clares – the same wine Father Magro had complained of on my first visit – which accompanied that first course. No doubt about, it was indeed weak and diluted. Then came the turn of spaghetti alle vongole, also presented on stainless steel trays, that arrived with rigor mortis imprinted on its tangles of pasta, studded with tiny fragments of clams and squid. There was no time for a second round as the next several courses – served by a small army of elderly volunteers – followed in rapid sequence: baked cod encrusted with breadcrumbs and aromatic herbs; a bowl of lentils; an omelette with zucchini cut as thin as paper. Finally dessert: a tray of oranges and clementines alternating with thick slices of Christmas panettone.

A new deafening scraping of chairs reverberated as the whole room rose to say a closing prayer. A cell phone rang; the swinging doors that separated the refectory from a long corridor to the kitchen swung open and closed vigorously until all traces of food were carried away. Fleeing volunteers and departing friars flocked to the door. As if infected by the general frenzy, Father Magro pushed me toward an exit. ‘We’ll have coffee at the bar,’ he whispered. I waited for him in a small anteroom while he changed clothes. He re-emerged in black pants, a turtleneck sweater, and a waterproof jacket. It’s a matter of respect for the people outside, he told me when we arrived in the neighboring town of Santa Maria degli Angeli, which stretches below Assisi. The bar seemed out of place, set in front of the imposing cathedral built over the Porziuncola, Saint Francis’ favorite hermitage: a nightmare of chrome and 1970s mirrors, with plasticized finishes. Father Magro assured me that he was not prejudiced against vestments; he was not even obliged to wear his cassock in the convent. ‘The point,’ he observed, ‘is that some people are suspicious and distrustful of those who stand out. While secular clothing is constantly changing with fashion, religious vestments remain rooted in the past. That’s why when I go out I wear ‘civilian’ clothes. In this bar, for example, the owner might not like the arrival of a friar in full regalia.’ A skinny waitress tucked in tight jeans, hair bleached and spotted with black, approached and carefully placed the tray with our coffee on the table. ‘Here you go, Father,’ she said jovially