By David A. F. Sweet

The statues outside of Chicago ballparks could field a starting team – Ernie Banks, Fergie Jenkins, and others are seen swinging and throwing near Wrigley Field, while Frank Thomas, Luis Aparicio, and others stand by the gates of Guaranteed Rate Field. Statues of other Chicago sports legends, such as Michael Jordan and Bobby Hull, are embossed in bronze at the United Center.

Amranys Bobby Hull: Omri Amrany created this statue of legendary Blackhawk Bobby Hull.

All are the handiwork of one fine art studio in tiny Highwood whose proprietors – in quite an ironic twist – are not even sports fans.

“What excites us about the sports projects is the human figure in motion,” said Julie Rotblatt Amrany, who runs the 10,000-square-foot space with her husband, Omri Amrany. “We are both intrigued with human anatomy.”

A Highland Park native who has taught at The Art Institute of Chicago, Julie met Omri – who grew up in a kibbitz in Israel – at a café in Italy in the 1980s. Having just served six years in the Israeli military, Amri decided to study sculpture in Pietrasanta, where Michelangelo trekked to find the world’s purest marble.

“As everyone went to the computer, I went to the Stone Age,” he said.

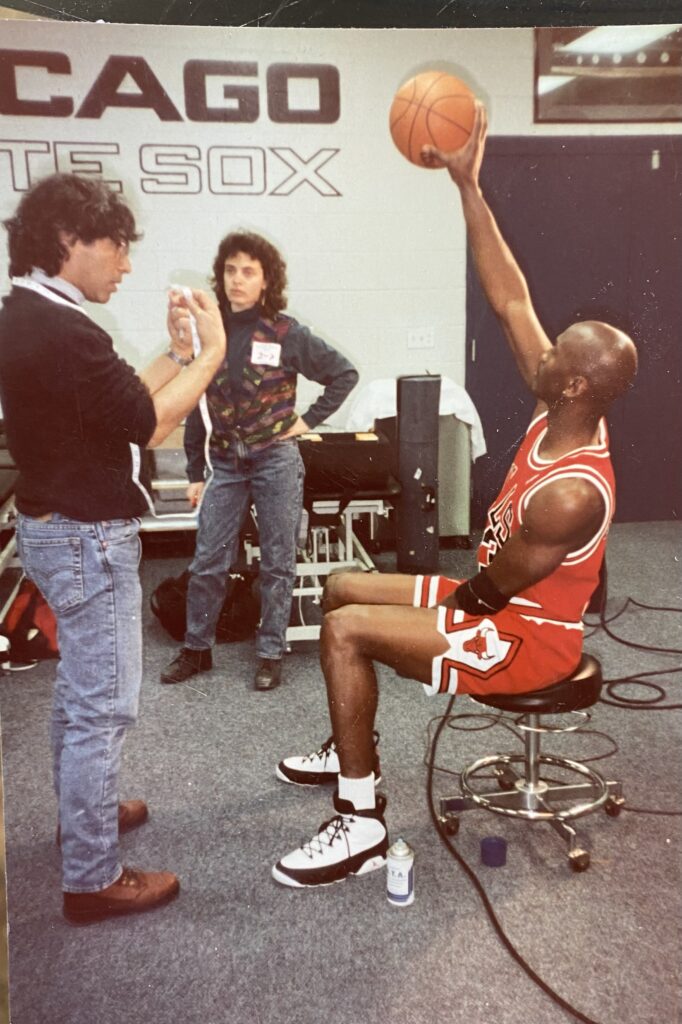

They moved to the Chicago area in 1989. Amazingly, within four years, they won a competition against a dozen other artists to design the statue of Michael Jordan soaring over a defender outside the United Center. After Jordan’s final game as a Bull during his first retirement, they met with him in a Chicago White Sox locker-room (far from the chaos of the Jordan-mad United Center) to measure him.

Amranys Magic Johnson: Omri Amrany, Julie Rotblatt Amrany and their son Itamar gather with Los Angeles Laker Hall of Famer Magic Johnson during the unveiling of his statue in 2004.

But almost as amazingly, that didn’t put them on the sports-statue map. That occurred five years later when Omri and the studio’s Lou Cella created a statue of Cubs’ announcer Harry Caray, microphone in hand and with faces of kids emerging from his lower body, which was unveiled outside of Wrigley Field. Over the next decade, the commissions poured in from all over the sports map, including Gordie Howe in Detroit and Magic Johnson in Los Angeles (Crypto.com Arena in L.A. features 10 of their statues, including a larger-than-life bronze of Shaquille O’Neal hanging from the rim after a dunk).

That Caray statue emphasized a differentiator the Amranys embrace: an arc of motion. At Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., pitcher Walter Johnson’s statue stands near those of Frank Howard and Josh Gibson. The motion of Johnson, one of the first Hall of Famers, is captured as his right arm moves, ball in hand, until it reaches his left knee.

Of course, some prefer standard statues. The Green Bay Packers shared a photograph of legendary coach Vince Lombardi. They wanted him in this position in this photograph – period.

Amranys Horse: The Highwood studio also develops many statues not related to sports.

In a former U.S. Army building at Fort Sheridan – which they bought for $1 before spending tens of thousands of dollars in renovations (there was nine feet of water in the basement to discharge) – the work takes place in private. Flanked by busts of Humphrey Bogart and others, a woman climbs on a ladder to sculpt a massive horse as part of a Civil War statue. In a nearby room sit the castings from original molds – along with two of Omri’s motorcycles.

One of the most elaborate works the studio sculpted did not involve sports. For the James A. Lovell Quest for Exploration at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, bronze, granite, glass, and steel were used rather than the typical bronze and granite.

Lovell visited the studio several times and shared his thoughts.

Amranys Michael Jordan: After his first retirement from the Chicago Bulls 30 years ago, Michael Jordan poses for Omri and Julie.

“When the person is still alive and involved, the project goes smoother,” said Julie, who noted the Lovell project was one of her favorites. “They may say to change their hair, change their chin – small things like that. They’re so appreciative.”

When a statue is finished, family members – seeing it for the first time – can react strongly. Julie remembered Chicago Bear owner Virginia McCaskey’s response when looking at the memorial of her father, George Halas.

“When she saw it, she started crying,” Julie recalled. “I knew I had struck the right chord.”

One time, though, Omri encountered a different reaction.

“When the woman looked at the face, she was almost in shock and said, ‘That’s not my husband!’” Omri recalled. “You’re dealing with people’s deepest emotions – sometimes their deepest sorrows. But as an artist, you have to be objective.”

Their work has evolved with technology. Many decades ago, Julie would draw client requests with pencil on paper. Once Photoshop arrived, the designs occurred there.

“It saved us a lot of time, and we could drop in photographs of the site,” Julie said. “Then clients could see what it would look like on their property.”

Projects can range from 6 months to 18 months. Installation usually is a matter of hours. Julie points out that after any unveiling, sculptures still need to be maintained, suggesting a cleaning followed by the application of a thin wax two or three times a year. Without it, the bronze will turn green.

Both Omri and Julie remain motivated after decades in the business.

Amranys Ernie Banks: The statue of Ernie Banks — also known as Mr. Cub — was created by Lou Cella of the studio.

“What excites me is doing ideas in different materials – you have to keep your brain challenged,” Julie said. “And you want to make sure you reflect your time period. Statues are nothing new – the Greeks were doing it.”

Julie will have a solo exhibition on May 11 at Oakton Community College.

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be reached at dafsweet@aol.com.