From the Author of Lost Chicago

By Megan McKinney

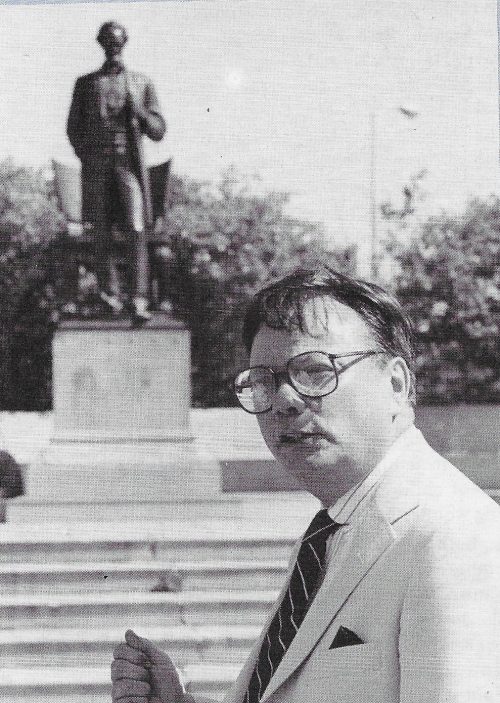

Architectural and cultural historian David Garrard Lowe with “the greatest public work of art in Chicago.”

Thirty years ago, Avenue M magazine Publisher Frank Sullivan asked David Garrard Lowe, author of the iconic Lost Chicago, to accompany him on a walk down Astor Street with this writer and a photographer. The result was a feature that appeared in the July 1987 issue of AVENUE M. With the approval of both Frank Sullivan and David Lowe, president of New York’s Beaux Arts Alliance, we are reproducing the memorable report here and over the next two weeks.

We begin at North Avenue with a view of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ statue of Lincoln. “This,” says David Lowe, “is really the greatest public work of art in Chicago; however, it is very disturbing that you have in America this insane idea of putting statues deep into parks where they can’t be seen. The scale of this wonderful statue would mean so much more if it were related to the street.”

Before starting down Astor Street, we pause at the magnificent Marshall & Fox apartment building that crowns North State Parkway at 1550.

1550 North State Parkway.

“This wonderful building,” he continues “is the kind of architecture of the École de Beaux-Arts that architects coming back from Paris at the time adopted to make American cities as beautiful as Paris. The model used to be beauty. The horror of the Bauhaus was that it brought the German idea of Socialist architecture from a country that was devastated in the First World War and was very poor. Mies’ idea that ‘Less is more,’ of course is not true. As Robert Venturi said, ‘Less is a bore.’ They brought the poverty of Europe to the richest country in the world and so you have people living in hideous buildings feeling badly about themselves. I repeat in Lost Chicago that great quote by Louis Sullivan, ‘Our architecture reflects us as truly as a mirror…’ and the other side of that is my own phrase. ‘We reflect our architecture like a mirror.’ People are better with beautiful things.”

We walk across the street to the Cardinal’s official residence set in a lawn of green stretching from North State Parkway to Astor Street facing North Avenue.

“There is no really old building that doesn’t look good to us now.”

“This 1880 structure by Alfred Pashley proves how a building can be an anchor for a neighborhood” David Lowe continues. “It was built as the Archbishop’s residence and is in that curious style of Queen Anne, which was just sort of taking any element of classical architectural design that you wanted to put together and you did it—columns, arches, whatever. They used to say ‘Queen Anne fronts and Mary Anne backs,’ because the architecture was so mixed up and strange. It is the official Archbishop’s residence and, therefore, there is a control on the property. Even when one or two archbishops had the insane idea to tear it down and live in an apartment, they weren’t allow to. That is very important because what we need are images like this. One of the great losses in Chicago is none of the great Lake Shore Drive palaces was saved as a residence for the mayor of Chicago.

The Queen Anne chimneys of the Archbishop’s residence in contrast to the Beaux Arts curves of 1550 North State Parkway.

“This is just a house that was considered hideous 20 years ago, and now it is sort of beloved. There is no really old building that doesn’t look good to us now. The Bauhaus has a real problem, and it will be the exception. Its foundation in ‘Less is more’ fit right in with the worst greed of American business. They could build the cheapest buildings and feel a justification for it. Saying that we will someday marvel at the work of the children of Bauhaus—the Mieslings as they say—is like saying that the tenements of lower East Side of New York will suddenly become beautiful. They won’t.

“One of the things that a house like the Archbishop’s residence provides is open space. A great loss in downtown Chicago is the disappearance of churches, and therefore the loss of open green spaces in the heart of the city that are so welcome when you walk around Boston, London, Paris or Trinity Church in New York.

The open space at Trinity Church, New York.

“Here,” he continues, gesturing across the street to the bare wall of a garage beside 1555 Astor, “is a real lesson in what I call modern brutality. At the entrance of one of the most desirable streets in Chicago, what do we have? We see almost half a block taken up with a brick wall that is a garage. First of all, it is a dangerous place to walk at night because, as Jane Jacobs said in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, there are no eyes. It is boring and it isn’t even good business. A small row of townhouses in that location could sell at a million dollars each.”

The children of the owners of the opulent Lake Shore Drive palaces built more subdued Georgian houses on Astor Street.

As we walk down Astor toward the 1518-1524 row of houses just below the Archbishop’s residence on the west side of the street, he continues. “Lake Shore Drive opened in 1875 from North to Oak and the first thing that was built was the Catholic Bishop of Chicago’s Addition—that is what this was called. South of it, Lake Shore Drive between Banks and Schiller, was the Potter Palmer Homestead, which was built in 1882. These were the anchors of the neighborhood. The Gilded Age mansions on Lake Shore Drive were built on an incredible scale. The average number of servants that was needed to run one was 13. That lasted until the turn of the century. Astor is the street of the children of those people. They wanted to scale down their lives. It wasn’t the money or the servant problem; they just didn’t want to be bothered with the effort of the opulence.” We stop in front of 1520 Astor.

The children of the Gilded Age “wanted to scale down their lives.”

“What you have with these houses is domestic English Georgian. The children of the owners of the Lake Shore Drive palaces were concerned with good manners and not too much opulence. It was like getting your clothes at Brooks Brothers and not wearing diamonds in the daytime.

1518 North Astor to the left.

“These houses are in contrast to Richard Morris Hunt’s French chateau and the Palmer’s English castle. By the turn of the century. Georgian had become the thing. It was very proper to be English and suddenly it became a sort of pseudo-WASP society in which the flamboyance of the earlier architecture was quickly disappearing. These houses,” he says of the 1518-1524 row, “were designed by Jenney, Mundie and Jensen in 1911, except for the house at the top of the row which was designed in 1968 by I. W. Colburn.

These are the houses of people who had been to Beacon Street in Boston—because they went to Harvard—or they had been in the squares of London and seen all those Regency houses. They came back and wanted to live that way.”

Stanford White’s Italian Renaissance house at Astor and Burton was built for Robert Patterson.

We continue walking south on the west side of Astor Street. “Here is McKim, Mead and White’s great house for Robert Patterson,” he says as we approach a colossal mansion with grounds on the northwest corner at Burton. “It was designed by Stanford White in 1892 when they were here working on the World’s Fair. The firm did a number of houses in Chicago. This is a very fine example of McKim, Mead and White’s Italian Renaissance style. What is so brilliant about it is the narrow Roman brick trim Stanford White was doing at the time. Notice the orange colors in the brick, of course, in all different tones so that it’s not boring. White, who was a classicist, and Louis Sullivan, who was not, both hated dead white buildings. They both said that in this kind of climate white was the worst possible color. It was blinding in the summer and freezing in the winter, whereas this is warm and rich.”

Author’s note: For a closer look at the brilliant McKim, Mead and White architect, we recommend David Garrard Lowe’s wonderful book, Stanford White’s New York, edited by Jacqueline Onassis and published by Doubleday in 1992.

The second of three segments of Megan McKinney’s David Lowe’s Astor Street will continue this series next week in Classic Chicago.

Photo Credit:

Selected images Laszlo Kondor

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl