By Cheryl Anderson

“Before me, no one would have dared to dress in black.….. A black so deep, so noble that once seen, it stays in the memory forever.”

—Chanel

It was about 1920 when Chanel said: “At about that time, I remember contemplating the auditorium at the Opera from the back of a box…those reds, those greens, those electric blues made me feel ill. These colors are impossible. These women, I’m bloody well going to dress them in black…. I imposed black; it’s still going strong today, for black wipes out everything else around.” She recounted this memory to Paul Morand, her friend and confident.

Chanel did not think all the bright colors she saw were suited to couture as did her rival at the time, couturier Paul Poiret. He had flooded the market with flashy colors and flamboyant designs. She felt they were more suited for the stage. In direct reference to her thoughts about Poiret’s fashions that she found distasteful, were that they were not chic saying: “…the richer the dress, the poorer it becomes.”

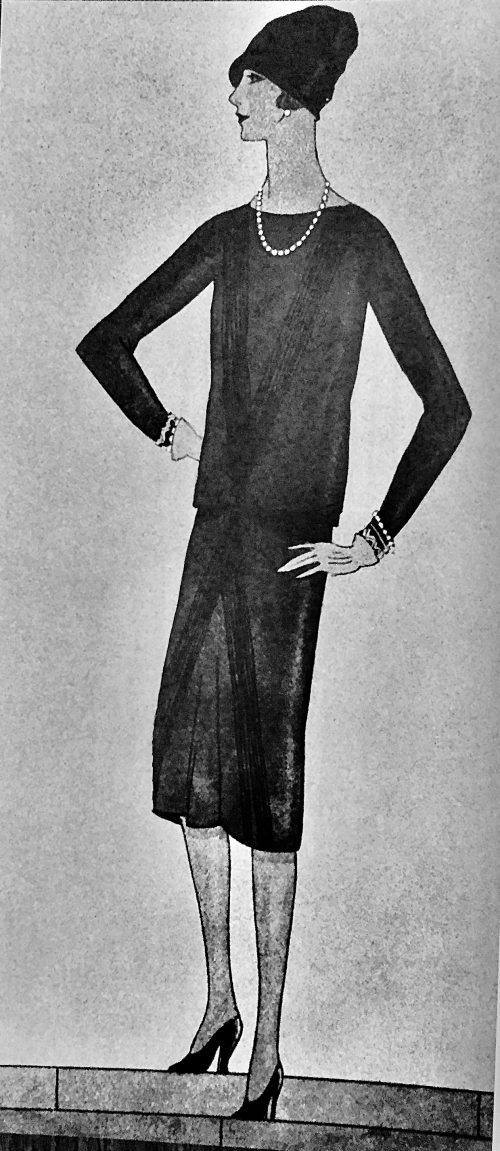

American Vogue October 1926. Original little black dress.

Chanel’s reasons for preferring the elegance of black can be found in her quote: “Nothing is more difficult to make than a little black dress. The entrancing tricks of Scheherazade are much easier to copy.” Poiret had this to say about the new Chanel creation: “What has Chanel invented? Deluxe poverty…. Now they resemble little undernourished telegraph clerks.”

Vogue France April 1926 Variations of the little black dress in mousseline.

Coco Chanel declared: “Fashion should express the place, the moment…” Although the Great Depression reached France in the 1930s, later than the United States, they were still reeling from WWI. It was Chanel’s genius to offer a dress design that was affordable and boasting that those who were not wealthy could: “walk around like millionaires.” Simply put, women needed affordable fashion. From the beginning of Chanel’s career, simplicity was a keynote in her designs. The little black dress was a modern sheath for the modern woman— it hugged the contours of the body, sans frills, like a canvas that could easily be accessorized.

Her revolutionary introduction of the little black dress took black, heretofore saved for mourning and worn by peasants, to celebratory occasions evoking Chanel chic. She had done it with the jersey suit and was about to do it again shaking up the fashion world with the little black dress forever placing it in the fashion lexicon. Over and over she shook things up in the fashion world, so it’s not surprising that once again she made herself relevant with the little black dress. Suzanne Orlandi (1912), pictured in a long black velvet dress with a white collar, is thought to be Chanel’s first black dress design.

Fourteen years later, in 1926, the little black dress made its debut—a chemise with long sleeves made of crêpe de Chine with delicate pleats in a V-shape on the slightly bloused top and skirt pared with pearls and a cloche hat. The sketch of this revolutionary design first appeared in American Vogue October 1926. The magazine realized its importance telling its readers: “Would one hesitate to buy an automobile because it could not be distinguished from another which of the same brand? On the contrary, for the similarity constituted a guarantee of quality. Here is the Ford signed ‘Chanel’.”

A Karl Lagerfeld sketch–his homage to the “Ford dress.”

The American market was the most enthusiastic about the little black dress in the beginning. Tagged “the Ford dress”—both the dress design and the car were widely accessible, each had simple lines and were black. For day, the dresses were made in wool or chenille and for evening, satin, crepe or velvet. The way the American market received the new design is described by Janet Wallach: “Despite its simplicity, however, it took a daring woman to design it and, oddly enough, an American audience to accept it. For all of Chanel’s characteristics, her clothes had a decidedly American appeal.” The author Anita Loos and the American editor of Harpers’s Bazaar, Carmelo Snow, were among those that loved the easy to wear and minimalistic design.

Susanne Orlandi (1912) photographed in what some consider Chanel’s first little black dress.

Chanel was responsible for making the cloche hat de rigueur. The caricaturist, Sem, had this to say about the hat: “As for the hats, they are nothing but plain tea strainers in soft felt, into which women plunge their heads by pulling down, with both hands clutching the bottom….They would surely have used a shoehorn, had this been suggested.”

A sketch appearing in Vogue April 1927 of Mme J.M. Sert in georgette outfits–a little black dress variation. The gazelle hound sports a coat by Chanel.

Other versions of Chanel’s little black dress appeared in Vogue France the same year as the launch, 1926. By 1928, there were some day dresses that flared a bit and were made of Moroccan crêpe and by 1929 she was using white trim for collars, cuffs, flowers, and pearls of course, perfectly accenting her little black dresses.

Pearl sautoirs accentuate the scooped back of the lace dress with panels of chiffon by Chanel. The drawing appeared in Vogue France 1927.

Chanel’s little black dress evolved with the times. Suit jackets and coat linings that matched the top worn underneath were among innovations she favored. Chanel was noted for taking an existing garment and applying her genius reinventing, and restyling statement pieces. No matter the changes, simplicity was always underlying her reasons for those changes, saying: “To my mind, simplicity is the keynote of all true elegance.” Her style became her brand and she herself expressed it best.

Drawing by Douglas Polland for Vogue shows the lining of the coat matching the top underneath that was a Chanel variation, made of Moroccan crepe and different styles of her cloche hats.

In 1939, she had a photo portrait done by George Hoyningen-Huene wearing a suit with a white collar. Another photo shows her looking at the model Muriel Maxwell wearing the same suit. The suit had long sleeves, the jacket was nipped in at the waist and featured a flattering peplum. The white collar on this suit evokes the one on the dress Orlandi wore—that is, high around the neck.

Why is the word “little” always the first word in the phrase when describing the black dress? The book, Chanel—Collections and Creations, explains it like this: “…because it was discreet yet essential, minimalistic yet elegant, obvious yet sophisticated.” She was the first to discreetly introduce black for both day and evening ware. Chanel’s designs mirrored The Art Deco movement with its sleek minimalistic lines free of adornment. George Bernard Shaw declared her: “the fashion wonder of the world.”

Drawing by Douglas Polland for Vogue with a garment in Moroccan crepe and a sleek cloche hat.

Chanel celebrated the success of her perfume and couturier collection by having a sculpture done of herself by Jacques Lipchitz and a portrait by her client Marie Laurencin, Portrait de Mademoiselle Chanel (1923)—it now hangs in the Louvre. She leased an apartment on the ground floor of the hôtel particular at 29, Faubourg Saint-Honoré, temporarily moving out of the Ritz. There she welcomed the avant-garde, artists, writers, and musicians—many evenings she surrounded herself with such creative people enjoying brilliant conversation that such a group brought.

It’s interesting to explore the reasons biographers have put forth for Chanel’s fascination with black. The exact reason is not known and explanations vary. She was complicated. Were her reasons memories of her time at Aubazine and having to wear a drab uniform every day, her sad childhood, black being symbolic or was she reminded of her solitude at the orphanage? She found solitude very difficult, but I read she never feared it. Chanel’s solitude was explained by Paul Morand: “…her only refuge was the ‘little old country cemetery’ where she felt like a ‘queen in a secret garden’.” Chanel once said: “Solitude destroys a woman….. Solitude is awkward.”

A little black dress in satin with Art Deco interior décor. Vogue January 1927.

To quote from, Chanel—Collections and Creations: “Or did the idea come later, when she discovered the almost erotic strictness of the black dresses with white trimmings worn by chambermaids and household servants.” Who’s to know? But the abyss of darkness she fell into after the death of Boy Capel, the love of her life, is, I think, the most compelling reason I have read, telling Paul Morand: “In losing Capel, I lost everything.”

Boy Capel died in an auto accident on December 22, 1919. Chanel mourned his death for a long time, but it did not crush her. Instead she launched herself forward, the Jazz Age was at hand. Six months after Capel’s death Chanel shared with Paul Morand an incident that had happened to her telling him she had received a visit from a Hindu gentleman. He had a message for her from someone she knew, saying: “This person is living in a place of happiness.” What he told her has forever remained a secret, she never told anyone. But, she told Morand: “it was a secret that no one, other than Capel and I, could have known.” Whatever was the message it’s believed to have restored her faith in the love of her life.

A little black dress in voile in front of Art Deco interior décor. Vogue January 1927

Interesting to note, is that Boy Capel was a theosophist and had told Chanel there was life after death. She told Claude Delay that Capel had once said to her: “Nothing dies, not even a grain of sand, so nothing is lost.” Further telling him that, she liked that very much.

With the £40,000 inheritance she received from Capel’s estate, she expanded her premises on rue Cambon and bought her own villa, Bel Respiro in Garches outside of Paris. She had it painted beige on the outside and shutters lacquered in black. For her house in Saint Cloud, where Capel had visited, she decided her bedroom should be all black, walls, ceiling, carpet, and sheets in his memory. She spent just one night there and according to Justine Picardie said: “Get me out of this tomb.” It was immediately decorated in pink.

Criticism of her and her new little black dress was harsh. Male journalists had this to say: “no more bosom, no more stomach, no more rump…. Feminine fashion of this moment in the 20th century will be baptized lop off everything.”

Chanel with society ladies in white and Lady Pamela Smith at a fitting session in London 1932. The little black dress with white collar and cuffs.

In 1922, the bestselling novel, La Garsonne, by Victor Marqueritte, Janet Wallach says: “featured a tomboy with cropped hair, flat figure and angular clothes who had an independent bent and an almost arrogant air.” Some have said Margueritte was inspired by Chanel. If so, the description of the girl in the book was not flattering with her bobbed hair, arched eyebrows, roughed lips, and painted nails—the writer saying: “thinks and acts like a man.” One can see how Chanel was an inspiration to him, both his character and Chanel were certainly independent, strong minded women. Perhaps, the popularity of La Garsonne had unintended consequences, and promoted the success of Chanel’s modern look.

Whereas, in her friend Paul Morand’s book, Lewis and Irène, his heroine was portrayed as a shrewd and successful businesswoman. It’s said to be based on Chanel’s affair with Boy Capel—Morand understood her the best.

Jean Cocteau, her friend, told Chanel that she had a masculine mind. Janet Wallach tells of Chanel’s reaction to what he had said to her: “The designer reacted with fury… Defiantly, she tied a ribbon around her head and knotted it with a bow…The action was spontaneous, but the headband and bow became part of her style.”

Chanel was not one to shy away from publicity or the limelight. Her public image was undeniably powerful— she never avoided photographers, weathered the unending gossip she endured, was part of the smart-set on the Riviera and attended the most glamorous evenings. Her associations with high-profile lovers was the reason for a lot of the gossip, once saying: “My love life got very disorganized.”

Chanel reworking a garment on a live model, as was her custom. Photo by Douglas Kirkland in the late sixties.

Where other designers failed to produce a black dress, Chanel succeeded for day, cocktail hour, and evening. The little black dress became the uniform for ladies with sophisticated tastes. Chanel said: “A woman can be overdressed, but never over elegant.” The simplicity of the little black dress could never be considered overdressed. To this day, it’s considered a garment one can rely on to be a good choice.

The beautiful portrait she had done by George Hoyningen-Huene in 1939. It somehow evokes a school girl. She had come a long way from her unhappy school days in Aubazine.

Women followed her, as they so often did, through all her revolutionary changes in fashion. Black was to become the symbol of freedom and strength. She had freed women from the restrictions of the corset, cut her hair and sat in the sun to get a tan. Once again with the color black, Coco Chanel revolutionized fashion.

For all the choices we have and decisions we are called upon to make every day. I find it a pleasure to have a little black dress in my closet making one decision easier, and to never second guess the choice.

À bientôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson