By Cheryl Anderson

“Simplicity is the keynote to all true elegance.”

—Coco Chanel

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel changed twentieth-century fashion forever. She began as a modiste (hatmaker) — her unique hats got her noticed. Next would be the simplicity of her revolutionary fashion designs and the beginning of the House of Chanel.

Coco’s first shop was in Paris — opening in late 1910. She was living with Arthur “Boy” Capel in his elegant Paris apartment on Avenue Gabriel. She made her hats upstairs at 21, rue Cambon — the plaque on the door read Chanel Modes. History tells us the rue Cambon would be associated with her onward.

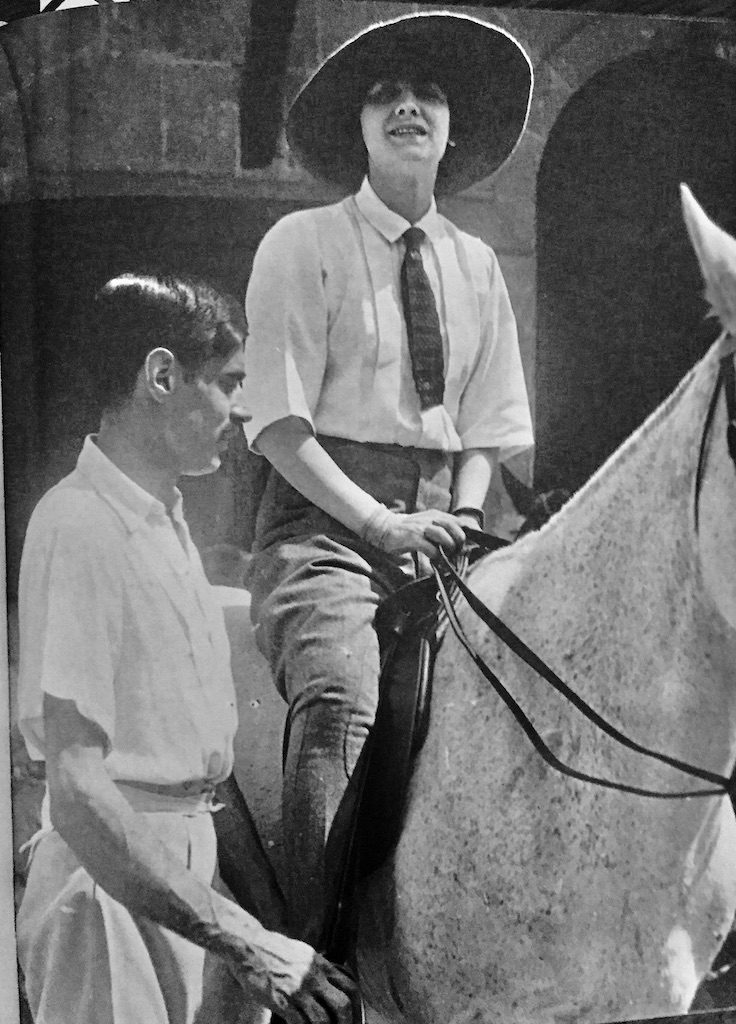

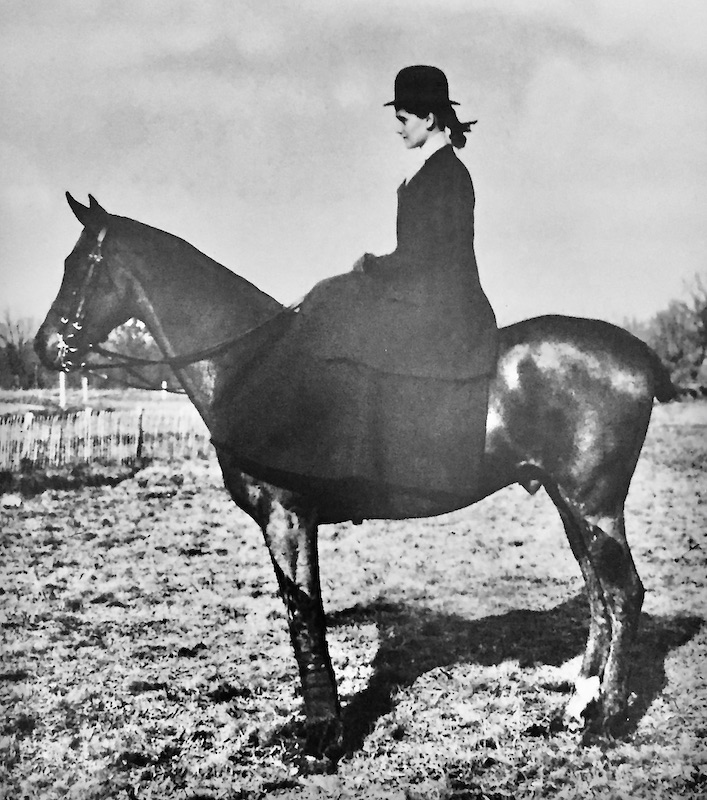

Chanel with Boy Capel in her jodhpurs.

Boy Capel, an English millionaire and handsome polo-player, would become Coco’s love of her life. Himself an entrepreneur, he took her desire to make hats more seriously than Ètienne Balsan, with whom she had previously lived at his family estate, Royallieu, outside of Paris. Capel understood her desire to become self-sufficient.

Among her early influential clients were some of the ladies and horsewomen she knew from when she lived with Balsan, many of whom were photographed appearing in the important fashion magazines at the time — all were wearing Chanel’s hats. Actresses and singers were among the ardent fans of her hats. Mlle Dorziat, of Vaudeville fame, was photographed numerous times sporting a hat designed by Chanel — that sort of advertising was priceless. Les Modes magazine, a powerful fashion influencer, spotlighted by name the new hatmaker, Gabrielle Chanel.

Mlle Dorziat, of Vaudeville fame, in a hat by Chanel — this hat is quite flashy, others show Dorziat in less dramatic creations by Chanel.

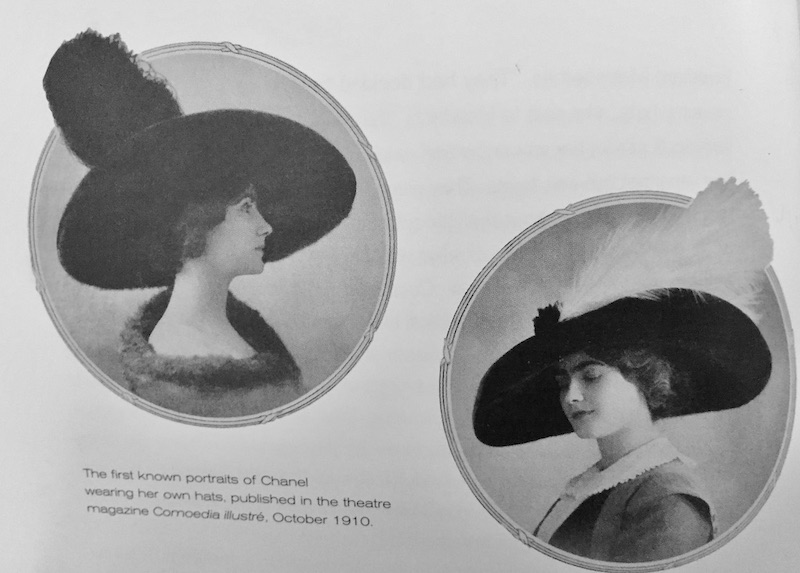

Chanel’s hats were significantly different from the popular Belle Èpoque styles — hers were sleek, minimally decorated, sans the era’s frilly embellishments of vast amounts of plumage, gauze and muslin roses. Such froufrou made them very heavy and so uncomfortable that they produced headaches. When asked about those hats, “It was grotesque, declared Chanel. ‘How could a brain function normally under all that?’ ” And, important to Coco, hers hugged one’s head instead of perching on top. As time went on not all of her hats had wide brims — photographs document the variety.

Appearing in the magazine Comoedia IIlustré (1910) — first known picture of Chanel in her own hat.

In 1912, it became known that Coco Chanel, the modiste, could make dresses as well as hats. A few socialites learned of this and went to her for help putting together their wardrobes. A keen sense of competitiveness took over Chanel to compete with the top designers of the day, Worth, Doucet, and Poiret.

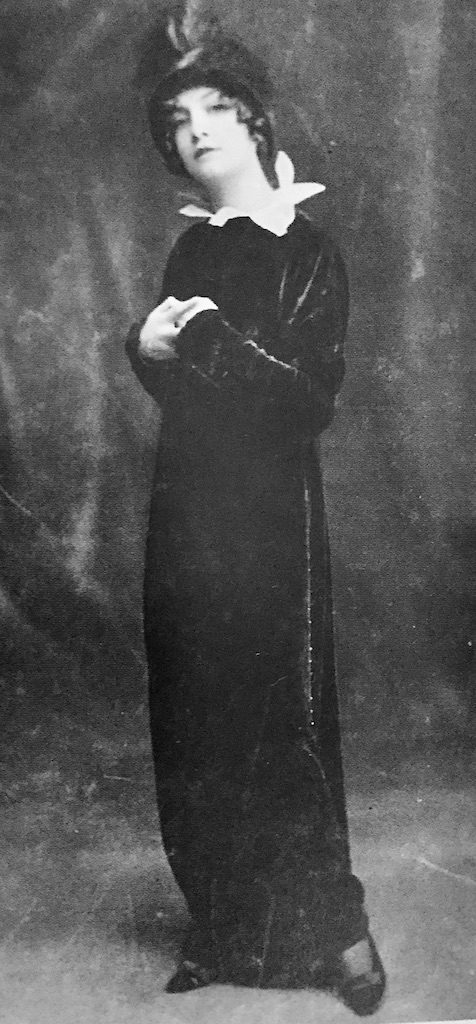

A photo of Suzanne Orlandi, Chanel’s friend, shows her dressed in what, “what may be her (Coco’s) first professional dress design, 1913,” says Edmonde Charles-Roux, Chanel’s friend and official biographer. The long black velvet gown with a flattering white collar proves that the Chanel look emoted chic simplicity from the very beginning.

Suzanne Orlandi in a hat from Chanel Modes dressed in what could possibly be Chanel’s first professional dress design (1913) — black velvet with white lawn petal collar.

She chose not to dress like the “fashionistas.” Their exaggerated frilly and fussy Belle-Èpoque style with their elaborate trims did not appeal to her— preferring instead to dress simply, more like an English gentleman. In the words of Charles-Roux, “…Gabrielle had discovered the fundamental principle of her art: elements of male attire adapted for feminine use.” Chanel shocked people when she had jodhpurs made for herself and a ponytail hung down from under a bowler riding hat. Paul Morand was a friend and confidant describing Chanel thusly: “that avant-garde of country girls in underskirts and flat shoes characterized by Marivaux; girls who go out, confront the dangers of the city, and triumph, doing so with the kind of solid appetite for vengeance that revolutions are made of.” Marivaux was one of the most important French playwrights in the 18th century.

Chanel with her dogs on the Deauville boardwalk.

Coco lamented that her severe black convent uniform, sans pretty pèlerines adorned with Holy Ghost or children of Mary ribbons, were only for the privileged students — she remembered this early “fashion” experience. Perhaps, I wonder, even then was she thinking comfort and simplicity could be pretty and chic? It’s obvious that Coco Chanel’s understated designs stood out in the Belle Èpoque environment. Later in life she is quoted as saying that, “Nothing makes a woman look older than obvious expensiveness, ornateness, complication.”

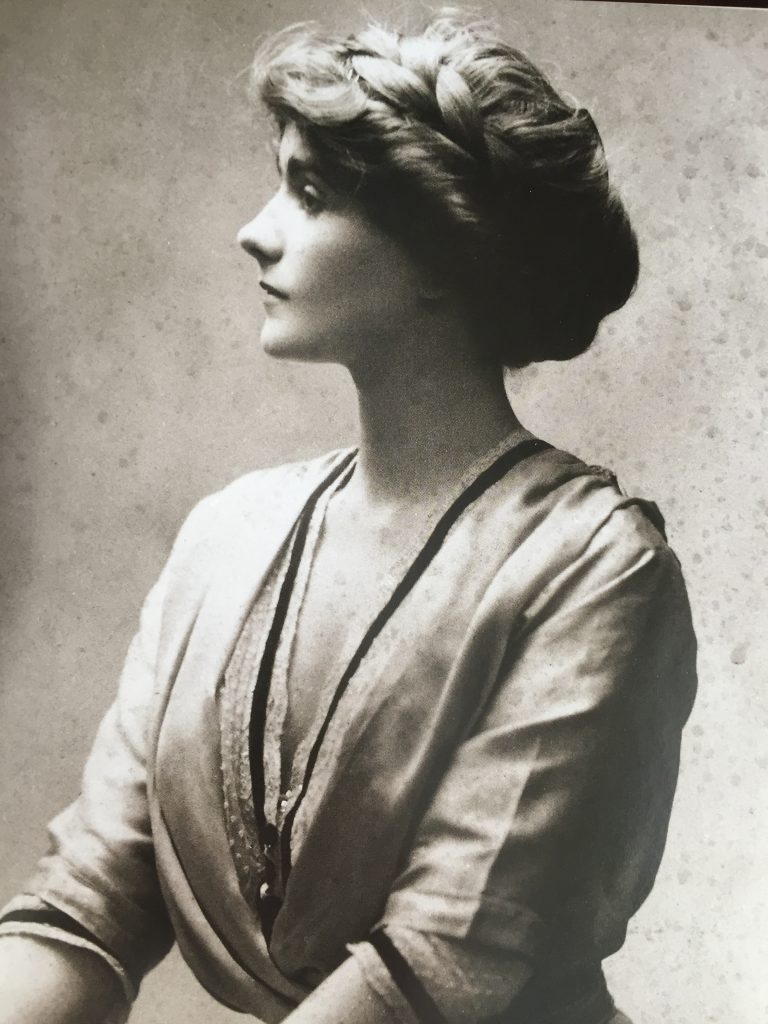

Gabrielle Chanel (1909) — modestie simply adorned with ribbon.

Less than a year before World War One broke out, financed by Boy Capel, Chanel opened a boutique in the Normandy coastal town of Deauville by the seaside where the well-to-do recreated. A striped awning above the shop read, Gabrielle Chanel — and of course, it was in the fashionable part of town. By 1913 many had fled Paris to shelter in Deauville from the impending war. Capel encouraged Chanel to stay in Deauville and not close the shop.

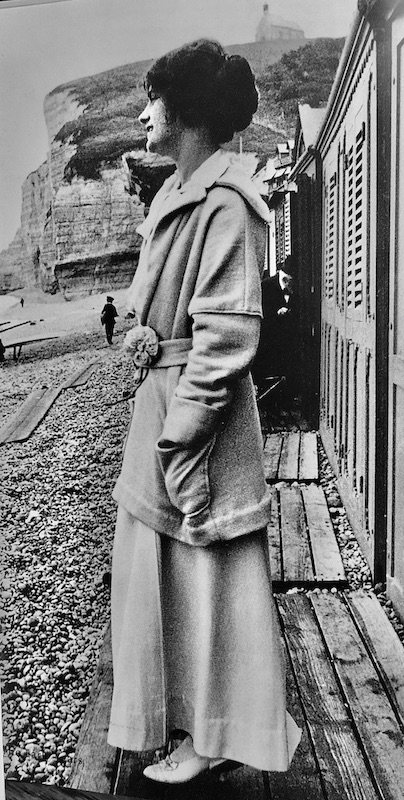

Chanel in Deauville under the awning emblazoned with Gabrielle Chanel — her first boutique.

Charles-Roux puts the results of the move to Deauville this way: “And nothing could stop her, not even the war that exploded within a year, nor yet the rumble of cannons sounding all the way from Verdun. Once she began to apply herself, Chanel became a femme d’entreprise forever.” Chanel’s life had a difficult beginning, but her raison d’être from that moment on would be to succeed as a force in the world of fashion. It marked the beginning of finding her freedom.

Chanel in Deauville (1913).

Her clients in Deauville were wealthy women, seeking refuge from the war and they needed new clothes. Chanel would give them functional clothes more suitable to be worn at a seaside resort — they were styles for outdoor living and comfortable enough to relax in, no corset required. Her inspiration came from Norman fishermen. She even designed a modest bathing costume made of soft jersey fabric like that used in Boy’s sweaters.

Chanel pictured in the modest bathing costume she designed (1914)

Further changing resort ware, sometime between 1920-1925, Chanel created the beach pajama — causing quite a stir was a woman seen in pants, even on the beach. It became popular on the Riviera to wear ropes of pearls with the new beachwear — ropes of pearls were made popular by Chanel.

Chanel in her fashion-forward beach pajamas.

In the shop, were large minimally decorated hats of course, and soon to be added were jumpers, jackets, and what would become the wartime garment for the well turned out lady, the marinière (sailor blouse). In the words of Chanel, “Fashion should express the place, the moment… I was witnessing the passing of the nineteenth century, the end of an era.” Her designs were the right look for the somber mood of the times — jackets made from tricot never before used for fashions, straight skirts and sailor blouses free of decoration. With more and more of the wealthy flooding into Deauville, business exceeded all expectations.

Chanel dressed in her new design made of tricot heretofore never used for fashion.

Coco’s decision to open a maison de couture in the Côte Basque town of Biarritz was prompted by a weekend trip there she had taken with Capel. Royals from all over Europe chose the fashionable resort to wait out the war, making it a perfect place for the very wealthy to shop. In July 1916 she started arranging the new shop in a villa facing the casino — it was fully functioning by September. Her wealthy cosmopolitan clientele was longing for luxury as a diversion from the horrors of the war around them and Coco Chanel was there to fulfill their need.

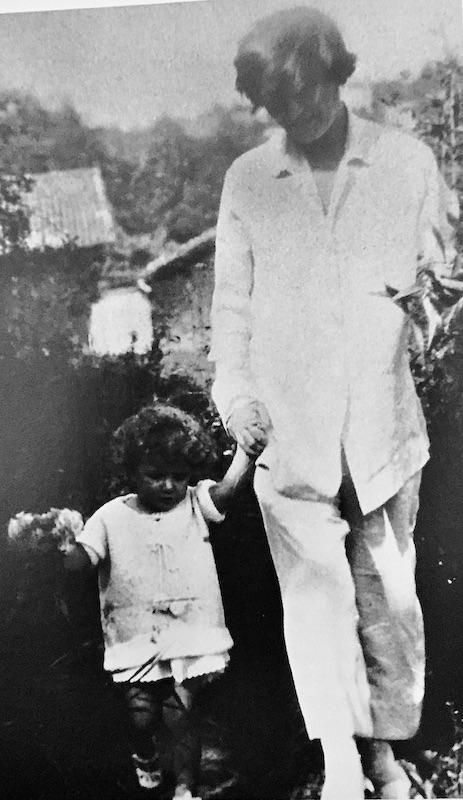

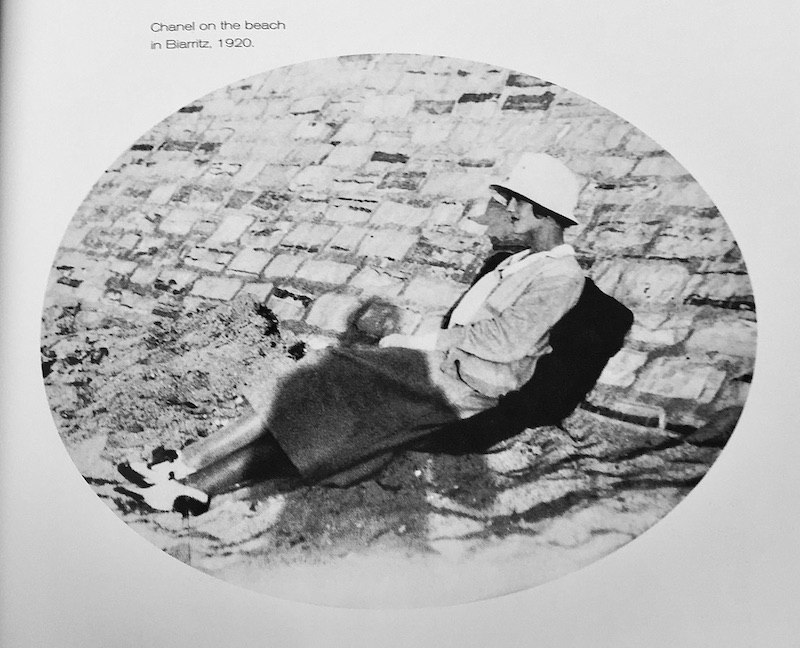

Chanel pictured in Biarritz (1920).

As it was close to the Spanish border, orders came flooding in from Madrid, Bilbao, San Sebastian, and the Spanish Court—Spain was a neutral country. The popularity of her relaxed clothing designs and large brimmed hats created a sensation on the Normandy shore. Chanel sold dresses costing as much as three thousand francs each. Her empire was growing — she was now in charge of directing approximately three hundred employees and able to reimburse Boy Capel.

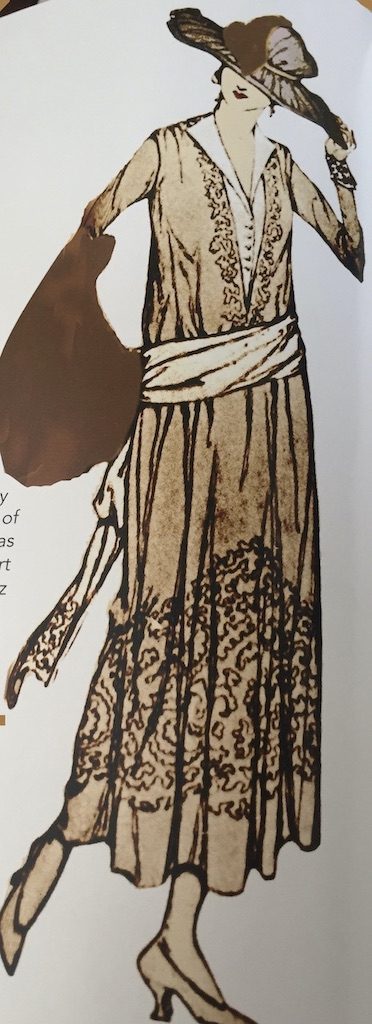

The first Chanel design ever published was in Harper’s Bazaar issue in 1916, calling it “the ‘charming chemise dress’ of Chanel.” It was from the Biarritz collection. Everything about it was unstructured except for a sash tied around the hips — a completely new silhouette.

Chanel’s completely different silhouette — Biarritz collection (1916).

The war had changed women and they were ready to embrace the new fashion trend that Chanel had begun. Shocking all who traveled to Paris, remaining exclusively in Paris generally from 1917 until 1919, was the daring exposure of a lady’s ankle. Ladies were walking more as there were fewer taxis, there weren’t as many chauffeurs as before the war, and gas was rationed.

The “new” ensemble appeared in Les Èlégance in 1917 — along with a full-page ad announcing the use of jersey with hats and dresses by Gabrielle Chanel.

Chanel’s new ensemble made it easier for walking and riding on a completely new mode of transportation! — Paris 1917

Needing fabric for her new clothing line, Rodier’s machine-made jersey was the solution. It felt soft like cashmere, draped well, was not expensive, suited her fluid designs, was sufficient in supply and perfect for her long tops over fuller and shorter more comfortable skirts. Due to the war, there was a shortage of other fabrics. Jersey was a fabric that heretofore had not been thought of as being worthy of haute couture. The new combination of longer belted tops or cardigan jackets and shorter fuller skirts could be called the first Chanel Suit.

No longer were women wanting to merely be models showing off riches, furs, layers, and layers of fabric, lace, and embroidery. Chanel gave them functionality and comfort replacing the constricting whalebone corsets. Short cropped hair appeared in May 1917 — Coco was a leader in that movement. Early photos show that she had masses of long dark brown hair, so it was an enormous change when she cut hers into a bob.

Chanel with a pony-tail under a bowler hat — completely audacious of her.

Simplicity is the single most common thread that runs through all of the revolutionary changes Chanel introduced, but the genius was that she made it chic. The driving force behind her was her determination to never be dependent on anyone — to never again be a kept woman.

Chanel with a very short bobbed haircut (1920).

Requiring more space for her burgeoning empire, she established her business on three floors at 31, rue Camdon in 1928 — that address remains the center of the House of Chanel. On one floor there’s a fabulous apartment with walls covered with Coromandel screens where she greeted friends, but she would sleep in a suite at the Ritz.