By Cheryl Anderson

“Ten years of my life have been spent with Westminster. The greatest pleasure he gave me was to watch him live. For ten years, I did everything he wanted. But fishing for salmon is not life.”

—Chanel

The setting: Monte Carlo, Hôtel de Paris during the Christmas season, December,1923.

The two principle players: Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, nickname, Bend’or. (Bend’or was the name of his grandfather’s derby-winning stallion.) She was there with her dear friend Vera Bate who was a friend of Bend’or. The Duke spotted Vera across the room and proceeded towards her table—he was asked to join their party. He decided not to go to the Casino and instead to party with them.

His, was an immediate attraction to the charismatic Coco, and Chanel was intrigued with the very elegant tall, blond man with striking blue eyes—the richest man in England. When Chanel referred to the Duke as the richest man in England she made clear what she meant: “I say this because, first of all, wealth of such magnitude ceases to be vulgar. It is beyond all envy and assumes the proportions of a catastrophe. Moreover, I say it because wealth makes Westminster the last representative of a departed civilization.” Also saying about him: “Elegant: that is detached.”

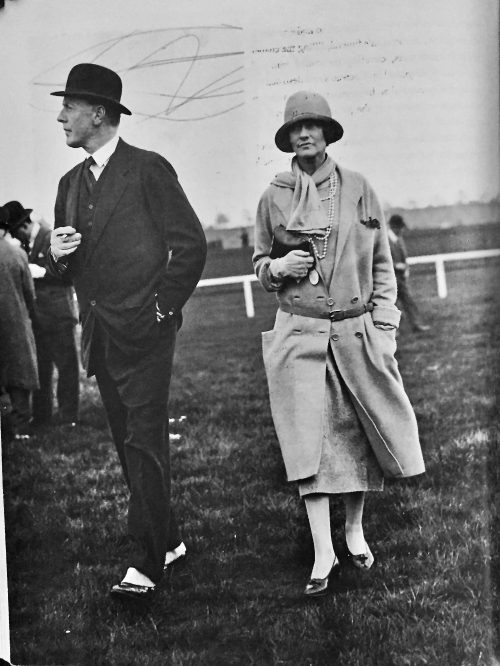

Chanel cloaked in fur with Westminster at the Grand National.

The day after their meeting at the Hôtel, Vera told her the Duke begged her to bring her fashion designer to dinner on his yacht, the Flying Cloud. Chanel refused, but Grand Duke Dimitri pleaded with her to accept the invitation as he wanted to meet Westminster and to see the interior of the legendary, Flying Cloud. Chanel relented, and accepted the invitation. Onboard, a gypsy band played and later they were off to a nightclub to dance.

Flying Cloud– the doorway.

Chanel with Marcelle Meyer looking very happy and jaunty aboard the Flying Cloud. Sailor cap pulled down low.

Chanel onboard the Flying Cloud.

The three guests were given a tour of the Flying Cloud. They entered through what resembled an old manor house with a heavy wood door, Greek columns and overhead was a carved shell decoration. The yacht was liked a country house at sea—among the largest private yachts in the world. It was a four-masted stay-sail, slick black, 282-foot long, 676-ton schooner with a crew of 40. They descended down a graceful staircase that entered into very elegant lodgings. The staterooms were paneled and the luxurious salons were decorated with Queen Anne furnishings and Italian silk fabrics. The Duke’s bedroom included a canopied bed and hand-blocked curtains. When he entertained onboard, there was a small orchestra so the guests could dance, and adding to the festive atmosphere, the rigging was illuminated when he entertained.

The Duke had purchased the yacht around 1921 and christened her the Flying Cloud. Winston Churchill wrote to his wife, Clementine, in August 1923: “This is a most attractive yacht.” The sea was Westminster’s passion, and I read that he especially loved heavy weather— for rougher seas he used his other vessel, the Cutty Sark, a former destroyer with a crew of 180.

Winston Churchill and Chanel at Eaton Hall, 1929.

Monaco and Monte Carlo were where the rich Europeans gathered. Christmas 1923 would find the harbor filled with yachts and the trees throughout the town festooned with sparkling lights. All was right with the world in 1923, the soigné celebrants at the Café de Paris for aperitifs and dining at the Hôtel de Paris right across the way. The Casino provided private rooms for gambling. Guests noticed other guests—with digression of course.

Chanel was on the Riviera to relax, to observe society at play, and escape, for a while, the bleak days in Paris—and to get over the stress of having helped her friend, Jean Cocteau, recover from the untimely death of his very young lover from typhoid.

Churchill, Linda and Cole Porter and Somerset Maugham were among Vera’s group of friends. Vera was employed by Chanel promoting the designer’s clothes wearing them everywhere, she wore them beautifully—Chanel gave her the clothes. As important as that was, Vera afforded Chanel her relationships with the English court. It was Vera that introduced Chanel to the Prince of Wales, the life of racing, fox-hunting and the beautiful lady riders there at Eaton Hall after her introduction to Bend’or. Chanel was familiar with the “horsey set” and their ways from her days at Royallieu twenty-five years earlier. Charles-Roux claims Vera: “earned her keep”.

Eaton Hall as it was when Chanel was there.

Chanel on the terrace at Eaton Hall.

An example of how close Vera was to the English court, Charles-Roux tells of an incident that occurred at Chanel’s residence at 29, Faubourg Saint-Honoré. A young man, whom the butler had never seen before, rang the doorbell. He told the butler he was to meet Vera Bate, but was told she was not there at the moment—he impressed the butler so much he was invited to wait for her return. The young man spent two hours with the chef in what is described as an animated conversation. Vera returned and the butler asks the visitor whom should he say is calling? The visitor replies: “The Prince of Wales”. Vera rushed in and gave him a hearty embrace. They were close friends and perhaps even more than, it’s thought.

Vera Bate with her friend Westminster in Scotland.

Coco took her time to succumb to Westminster’s attention towards her—she was at the peak of her success. She had become “the” French couturier two years before meeting Bend’or—her eponymous little black dress and perfume had been successfully launched. Chanel refused Bend’or’s many and persistent advances wondering what more could she want? Her work and independence always remained important.

Westminster courted Chanel with stubborn determination, one might even say with a frenzy, for three months. He was intrigued with her obstinacy and self-sufficiency making her more attractive. He was usually the one being chased, therefore, Chanel ignoring his attention was new to him. All the while, she worked in Paris on her spring collection.

He showered her with gifts—baskets of exotic produce from his hothouses at Eaton Hall, foods that were not readily bought. Among the foods, were out-of-season strawberries, peaches, nectarines and freshly caught Scottish salmon from his estate, gardenias and orchids from his gardens, works of art and fabulous jewels. There are stories surrounding these offerings. One being, that while her butler was unpacking a crate of fresh vegetables, hidden at the bottom in a jewel case was a very large uncut emerald. Another time, when Chanel’s manservant answered the door, behind the huge bouquet was the Duke. A few days later he showed up at her apartment on the Faubourg Saint-Honoré with another massive bouquet and the Prince of Wales, proving to her he was a royal equal. I would assume she was impressed by all this, but she would not allow herself to be just another one of his conquests. But, when he finally won her over they were constantly at each other’s side. They instantly became an “item”.

Chanel and Westminster happy together at Eaton Hall.

Chanel in the garden at Eaton Hall.

It was in the late spring of 1924 when Coco made her decision between Dimitri, her lover at the time, whom she was supporting, and Westminster— she weighed the losses and gains, telling Claude Delay: “I chose the one who protected me best.” Westminster was like Boy Capel in that they were both well-known womanizers. Could she again accept the fact that love like money could not be counted on? It was Westminster’s wealth that made it easy for all of his numerous infidelities. At last, she succumbed to Westminster’s charming ways—but, she never neglected her business.

That spring, they boarded the Flying Cloud and sailed the Mediterranean where she experienced luxury beyond her imagination. She slipped into the role of châtelaine at Eaton Hall, in Cheshire: “…with the same ease as she wore her silk fringed evening gowns.”, as Picardie puts it, and enjoyed cruises aboard the Flying Cloud, telling Claude Delay, that a yacht is the best place to start an affair. She came back to Paris from a cruise, “brown as a cabin boy”. We know she had made tanning fashionable.

The magnificent Flying Cloud–a country house, on a grand scale, at sea.

Chanel on deck of the Flying Cloud.

The publicity was huge when he took her across the Channel to his celebration at the Chester Club and they appeared at the race track—she, wearing his polo coat that she belted. As usual, women around the world followed Chanel’s style, and began belting their coats.

Westminster’s polo coat belted by Chanel at the Chester races,1924– the trend copied round the world.

Indeed, the 2nd Duke of Westminster’s properties were vast. Largest of all his residences was Eaton Hall, the Westminster country seat. Even if exaggerated, I read it took 15 hours to tour the entire estate. Other residences included, holdings in much of Mayfair and Belgravia, property rights to the Grosvenor House in London (later leased to the United States as the American Embassy), a château in France near Rouen, a hunting lodge called Mimizan in the Landes between Bordeaux and Biarritz, being so isolated in the pine woods it took special cars to reach it.

Chanel and the Duke’s favorite dachshund at Mimiizan, his hunting lodge in France.

To Paul Morand she said: “On every new trip, I discovered them…in Ireland, in Dalmatia, or in the Carpathians, there is a house belonging to Westminster, a house where everything is set up…”.

When Churchill, closest friend to Westminster since the Boer War, was visiting Mimizan for a weekend boar-hunting trip, Chanel was there. On January 27, 1927 he penned a letter to his wife,: “The famous Coco turned up and I took a gt fancy to her—A most capable & agreeable woman—much the strongest personality Benny has yet been up against. She hunted vigorously all day, motored to Paris after dinner, & is today engaged in passing & improving dresses on endless streams of mannequins.”

A pensive Chanel at Mimizan.

Chanel and Churchill would cross paths many times at house parties, on the Flying Cloud and he was a frequent visitor to her workrooms in rue Cambon in Paris. Fishing records show that as early as May 27, 1925, Chanel caught salmon at Lochmore—it appears that she was very skilled at fishing. Most everything Chanel did, she did well. Once saying: “I’ve never done anything by halves”. Janet Wallach explains her drive: “She had a singular drive to succeed, and her standards measured success at only the highest levels. Whether courtesan or consort, sportswoman or entrepreneur, she aimed for the top and accepted nothing less of herself.”

Fishing records from Lochmore, 1927.

Chanel and Vera Bate at Lochmore wearing “borrowed” clothes–having fun.

Chanel with her catch of the day at Lochmore,1928.

Westminster brought new amusements to Eaton thus modernizing it. Of course, there was hunting and shooting, but he provided cricket, croquet, tennis, boating and a nine-hole golf course. There was a regular polo tournament—10 teams and 92 ponies were put up for a week. I can’t imagine anyone of the guests ever being bored—something to do every minute of the day. Quoting George Wyndom: “The whole place has been turned into the embodiment of a boy’s holiday.” Not an easy task at such a formal and imposing grand house—Bend’or established a youthful informality to its grandness.

The list of Westminster’s properties goes on—in Scotland, Stack Lodge, his estate in Lairg, and Saint-Saëns, hunting lodge, the ducal château in Normandy. In October 1927, from Stack Lodge, Churchill wrote to his wife: “Coco is here in place of Violet. She fishes from morn till night, & in 2 months has filed 50 salmon. She is vy agreeable—really a gt & strong being fit to rule a man or an Empire. Bennie vy well & I think extremely happy to be mated with an equal—her ability balancing her power. We are only 3 on the river (River Laxford) & have all the plums.” The other house on the Sutherland estate was Lochmore, a granite Victorian mansion with ducal splendor overlooking the loch. It was here where Bend’or died, in July 1953, after his return from a fishing expedition.

Randolph Churchill, Chanel and Winston Churchill at Mimizan.

Whenever he arrived unannounced at any of his properties, it was not a problem, because each house was always ready for even an unexpected arrival. Cars were fueled, silver was polished, servants dressed in Grosvenor livery and of course the larder was fully stocked. Being the richest man in England, he was always met with great distinction. Boats, cars and railroads delayed departure for him. At the London train stations, red carpets were laid out and special gangways were arranged for at the Channel steamers. It’s not too much to say that all of these gestures were those he fully expected. Westminster was not without devastating tragedy despite his wealthy and privileged life. In February 1904, his four-year-old son died of appendicitis at Eaton Hall.

She rode and hunted at Eaton Hall and went to races. When he bought Rosehall in the Highlands in 1926, she brought to it her characteristic style, painting the drawing rooms beige and hand-blocked French wallpaper on the bedroom walls—it’s said she had installed the first bidet in Scotland in an en-suite bathroom. Churchill wrote to his wife whilst on a fishing trip to Rosehall: “This is a vy agreeable house.” She charmed his friends, got along with his children and his first wife. She told Morand: “My friends bored him”.

Chanel wearing Westminster’s jacket in Scotland–yet looking very chic.

Westminster, instead of being restless with her at rue Cambon, he had her seamstresses shipped to Eaton Hall so she could work on a collection and be with him—even when he was with her there, however, he paced. But, he did join her in Paris for her shows in February and August. She told Delay: “The tiger paced up and down”, in rue Cambon, yet knowing she would join him in the evening. She organized her schedule to travel with him however and whenever he chose to make the journey.

Chanel got to know the servants and the head butler, became familiar with the immense galleries and salons of Eaton Hall. Usually, there were sixty guests in residence at Eaton. Weekends at grand English country houses, were from Thursday evening to Monday lunch. Eaton Hall was demolished after World War II.

Chanel to French Vogue: “The purpose of fashion is to make women look young. Then their outlook on life changes. They feel brighter and more cheerful.” She would bring that philosophy to her English inspired clothes. Coco had made her mark by this time—had been in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar by 1915. She was well prepared to take on the English smart-set she would be entering with Westminster. Chanel was ambivalent about Englishwomen, but she dressed them and she impressed them. After all, it was business.

Their meeting on that December evening led to Coco Chanel’s English Period, her English inspired collections emerging from 1926-31—adopting designs for her collections predominately from her exposure to Eaton Hall, and the ducal yachts. She softened Scottish tweed fabric and incorporated it into her collection. Westminster provided Chanel with a textile factory where she manufactured her own wools for suits and coats—tweed coats made more elegant when she lined them with fur. Fair Isle sweaters, a favorite of Scotsmen, she took for herself and made cardigans and pullovers for her collection.

Chanel wearing her fur-lined tweed coat.

Fair Isle sweaters, a favorite of Chanel, appeared in her English inspired collection.

To quote Wallach: “She recognized that male styles offered more than just ease; they afforded a sense of power…that a woman dressed in men’s clothes felt either emphatically feminine, like a fragile doll wrapped a masculine aura, or erotically androgynous.” From the yacht’s crew, she created her style of their peacoat with brass buttons, yachting caps given to guests aboard his yacht were made into berets that were pulled down low over the brow. Striped marinière sweaters, worn by the crew of the Flying Cloud, appeared under slim jackets with a matching pleated skirt in jersey or with trousers.

Chanel sporting the marinière sweater and bell-bottom pants she made famous.

Westminster’s blazers with shiny buttons, cuff-link shirts, his butler’s pinstriped vests and his chambermaid’s uniforms were seen in her collections, always adapting what she saw. Chanel and Vera “confiscated” their host’s jackets, sweaters, pants and at times even shoes. Chanel first took the ankle-length bell-bottom pant the yacht crew wore for herself and then adapted for her collection. They made sense for getting on and off yachts or boats and comfortable on a sandy beach—thus furthering the trouser idea for women, white silk pants and a black jersey top at the beach, and silk pajamas for evening wear. Other designer’s attempts at similar looks did not have as much impact as when Chanel appeared in fashion magazines did the trend truly take off. As Wallach puts it: “No one else wore pants with such panache.” She influenced women and trousers for the rest of the century.

The black-sleeved waistcoats with the ducal colors striped down the front, worn by Bend’or’s liveried footmen and butlers for their morning chores at Eaton Hall gave her ideas. She borrowed Westminster’s clothes at Lochmore, bringing a bit of Scotland into her tweed designs for women. Sailors on the Duke’s yacht, the Cutty Sark, and on the Flying Cloud I imagine, wore berets. Chanel made them fashionable for elegant ladies to wear—she liked to pin a brooch on hers thus adorning remarkable simplicity. Photos show that brooches on hats were one her favorite things to do.

Chanel wearing a sailor cap with a brooch.

At the same time, she was offering menswear-inspired clothing and slacks, as Wallach describes it: “she (also) introduced gossamer evening dresses made of delicate black lace. The gowns, sometimes embroidered with metallic threads, enhanced a woman’s flirtatiousness and seemed to turn the most jaded sophisticate into a fragile ingenue.”

Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar labeled her collection, “Chanel’s English Look”.—it included the loose woolen cardigans she was so fond of wearing with ropes of pearls. In early June 1927, the headline in British Vogue announced the most important news of the summer: “Chanel Opens Her London House”. Vogue went on to say: “Chanel, one of the most popular of great French couturiers, has come to London. In a beautiful Queen Anne house, with paneled walls and parquet floors, mannequins graceful and slender as lilies show Chanel’s latest collection.” The townhouse Westminster had given Chanel was close to his Georgian residence in Mayfair, Bourdon House, on Davies Street.

The very dapper Westminster and Chanel wearing one of his cardigans.

Illustrations in British Vogue showed four models with Chanel outfits suited for British society. For the debutant, two white taffeta gowns to wear to court sans adornment—chic simplicity. There were outfits suited for Ascot, a little black dress with lace and one other dress in blue silk polka dots.

Vogue went on to say: “We have seen in her collection a number of frocks designed for Ascot and those private functions for which in England one is more formally dressed than for similar functions in France…a Court dress a new idea, strikingly successful in the way it reconciles a charming modernism with a traditional formula. We love tradition as we love beautiful old houses, but we love also that element of youth which makes itself felt wherever it might be…the debutante presented at Court appears, flower-like and youthful, made more charming by the striking contrast she presents with the ancient walls of the Royal palace. The Chanel workrooms in London employ only English workgirls under the direction of French premières. Only English mannequins show the models. Here in an essentially practical sense, useful to both countries—to Great Britain and to France—is an entente cordiale, French chic adapted to English tastes and traditions.”

Once again, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was a triumph—this time, across the Channel.

What finally happened to bring an end to Chanel and Westminster’s love affair? Their break-up was inevitable as he was desperate for a male heir to his fortune and Chanel was unable to conceive, despite surgery and difficult special exercises. However, his womanizing humiliated her and was not an insignificant factor in the break-up—pretty women came onto his yacht appearing with him when she was there, further weakening their relationship. Westminster continued to shower her with expensive gifts, but they were not enough for her to tolerate his betrayal. One notable incident occurred after a particularly fierce argument about an attractive lady when they were onboard the Flying Cloud. He had given her a magnificent jewel. With a vengeance, she tossed the very expensive emerald overboard.

Both Westminster and Chanel had volatile tempers. He was impatient and she demanded time for her work. She enjoyed his friends and he could not tolerate hers. He didn’t “understand” her artist and writer friends and their enigmatic talk—he found it mystifying and baffling. Rarely did he join she and her friends when they went out to dine.

They did remain together for a time and when she built La Pausa, her villa retreat on the Riviera, there was a special suite for him. Their anger spilled over even there. Arguments were loud and could be overheard even though they were in their private wing. Their affair was certainly over, but they remained friends. Westminster met and married Loelia Posonley, half his age. When he took her over to meet Chanel, Coco made it as awkward as best she could—Posonley became a client.

The quote at the very beginning of this article is an instance where Chanel elides the time spent with Westminster. Their affair was generally from 1924-1931. In 1946, she spoke to Paul Morand: “Ten years of my life have been spent with Westminster…you’d have to be skilled to hang on to me for ten years. Those ten years were spent living very lovingly and very amicably with him. We have remained friends.” If she hadn’t met the Duke, she told a friend, she would have gone crazy from, ‘too much emotion, too much excitement’.”

“There have been many Duchesses of Westminster, but only one Chanel”, has often been attributed to Chanel having said it, in reference to refusing Westminster’s proposal. It is a myth. In her old age, she is quoted denying having said it or having anything to do with its origin: “He would have laughed in my face if I had ever said it.”, that it was too vulgar to have said that to Bend’or. Another possibility, and Justine Picardie says more likely of the origin of the quote, is from when she had lunch with Sir Charles Mendi at the British Embassy in Paris. He asked her: “why she had turned down Westminster’s proposal, she replied that there were ‘so many duchesses already, to which he replied, chivalrously, ‘and there is only one Coco Chanel’.” No proof exists that Bend’or had ever proposed to her.

Lasting reminders of Chanel and Bend’or’s time together are still in the gardens of Rosehall— white azaleas blossom as when Coco was there. In Mayfair, on some streets, there are double Cs embossed on old lampposts—the Duke’s lasting and loving gesture toward Coco Chanel. British tradition meeting French couture in a subtle yet stylish manner.

She came to love Bend’or, telling a friend: “My real life began with Westminster. I’d finally found a shoulder I could lean on, a tree against which I could prop myself.”

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson