By William Tyre

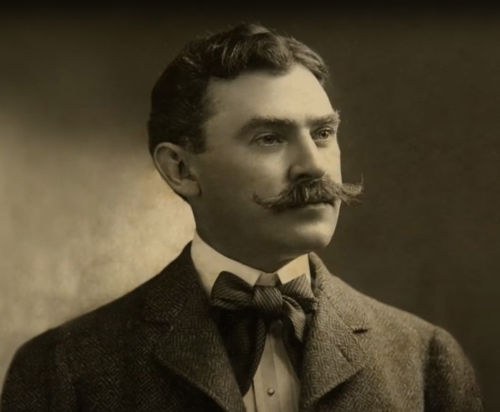

George Maher in the 1890s (Kenilworth Historical Society)

The year 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of architect George W. Maher. Often overshadowed by his contemporary and long-time friend, Frank Lloyd Wright, Maher produced an impressive body of work, and many of his buildings still stand in Chicago, Kenilworth, Oak Park, and elsewhere.

Architectural historian H. Allen Brooks, writing in his 1972 book, The Prairie School, Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwest Contemporaries” said of Maher:

“His influence on the Midwest was profound and prolonged and, in its time, was certainly as great as was Frank Lloyd Wright’s. Compared with the conventional architecture of the day, his work showed considerable freedom and originality, and his interiors were notable for their open and flowing space.”

Leach House, South Orange, New Jersey (Inland Architect)

George Washington Maher was born in Mill Creek, West Virginia on Christmas Day, 1864. The family later relocated to New Albany, Indiana, but by the time Maher was 18, he had struck out on his own, finding work as a draftsman in the office of Chicago architects Augustus Bauer and Henry W. Hill. In 1887, he accepted a position with architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee, where he worked beside Frank Lloyd Wright and George Grant Elmslie. In less than two years, he opened his own independent practice.

Maher wrote extensively about his ideas on architecture. In a paper entitled “Originality in American Architecture” prepared in 1887, he noted:

“Let us turn our attention to the American residence and note the improvement made on this class of building during the past few years. What was it originally? Generally, a structure boxy and meaningless in every detail; if a large building, perhaps a poor copy from some photograph of an edifice in Europe . . . What have we today? In most of our large cities a class of buildings can be seen which have no equal for interior arrangement, original to this class of buildings in every particular, for nowhere are the wants of comfort and practicability so sought after as here, and nowhere the world over are modern improvements so easily adapted as here . . . The late H. H. Richardson was the most prominent in placing this class of building on a substantial basis, and it is now receiving encouragement. The idea of massiveness, imposing centralization, of grouping novel ideas for comfort in the interior arrangement seem to be the motives most sought after.”

It is noteworthy that Maher delivered this paper in September 1887, just three months before John and Frances Glessner moved into their Richardson-designed Chicago home at 1800 S. Prairie Avenue. The last two sentences of Maher’s quote above describe the Glessner home perfectly. Frances Glessner noted in her journal that many architects came to see the house both during construction and after they moved in. It seems likely Maher was among them.

Glessner House, 1888

Maher’s early years focused on residences and small apartment buildings both in Chicago and nearby suburbs. On the south side, he designed a shingled, Colonial Revival-style house for his parents, plus several houses in response to the building boom leading up to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. A survival from the 1890s is the J. J. Dau house at 4807 S. Greenwood Avenue. The bright-red brick house features a massive limestone porch sheltering an arched entryway, echoing the center dormer above.

Dau House (Berkshire Hathaway)

In the Dau house, we see an early use of Maher’s signature design element which he referred to as his “motif rhythm theory.” Maher would select an indigenous plant and/or a geometric shape which would then be used as a unifying motif for the various elements of the composition. For the Dau house, the motif comprises a round shield and berry laden leaves. In other houses he incorporated thistles, poppies, and lilies, paired with squares, circles, and stars.

The motif was often represented in leaded glass windows, mosaic tile fireplace surrounds, textiles, and furniture produced by collaborators including Louis Millet, Giannini and Hilgart, Tiffany Studios, and Willy Lau. A number of these items, from demolished or remodeled houses, are now found in major museums across the country.

Fireplace from the King House (Art Institute of Chicago)

In 1893, Maher married Elizabeth Brooks, and the couple moved into a picturesque home he designed at 424 Warwick in Kenilworth. Set beneath a steeply pitched roof, the house has been described as a “piquant blend of Victorian, Chinese, Swiss Chalet, Gothic, and Arts and Crafts styles.” In the design of the house, Maher used the diamond pattern as his motif for roof shingles, windows, and interior details.

Maher House

Maher called Kenilworth home for the remainder of his life, and ultimately designed nearly 40 buildings for the North Shore community, the largest concentration of his work anywhere. Significant examples of his architectural development include the Maynard A. Cheney house (322 Woodstock, built 1900) emphasizing the broad horizontal massing and hipped roof with wide eaves made popular by Prairie School architects. The Francis Lackner House (521 Roslyn, built 1905) demonstrates Maher’s ability in working with more picturesque styles, the house displaying dramatic gables and exposed roof beams.

Cheney House (Inland Architect)

Lackner House (Chicago Architectural Club)

Maher’s most important design in Kenilworth was the Kenilworth Assembly Hall at 410 Kenilworth Avenue, completed in 1907 and expanded by him in 1913-1914. The design of the clubhouse was classic Prairie School, with the low-slung building hugging the ground, and the entrance literally embracing nature with its pergola built around an existing elm tree. The design motif incorporated consists of a stylized flower on a long stem, set within a diamond. It was extensively restored in the early 2000s.

Kenilworth Assembly Hall (Chicago Architectural Club)

Maher contributed designs for other elements of Kenilworth’s residential plan. At the west end of Kenilworth Avenue, he designed a large fountain with a central stone urn, containing a bronze fish which spouts water. It provided a welcoming element to the community, situated between the train station and the Assembly Hall. (To the other side is the Village Hall/Historical Society designed later by his son Philip). Elsewhere in the community, Maher designed charming bridges, urns, and pylons.

Fountain (Kenilworth Historical Society)

Chicago boasts a considerable number of Maher houses. A particularly fine collection of five structures can be found on the 700 and 800 blocks of West Hutchinson Street, and form part of the Hutchinson Street Historic District. The earliest of the five is the John C. Scales house at 840 W. Hutchinson, designed in 1894. The rusticated stone walls pay tribute to H. H. Richardson and Maher’s previous employer, Silsbee. By contrast, the William H. Lake house at 826 W. Hutchinson, designed exactly a decade later, shows Maher’s evolution with its strong horizontal lines and simple massing set beneath overhanging low hipped roofs.

Scales House (Inland Architect)

Lake House (Inland Architect)

Three additional Maher-designed houses in the city have been designated as individual landmarks. The Patrick J. King house at 3234 W. Washington Blvd was designed in 1901 with influences of the Richardsonian Romanesque. The house is noted for its richly carved columns and urns. The thistle forms the recurring motif.

King House (Inland Architect)

The John Rath house at 2701 W. Logan Blvd. of 1907 is even more impressive with its low Prairie School profile, deep recessed porch and bands of floral-patterned leaded glass windows. The house displays a trademark Maher design feature known as a flanged segmental arch, consisting of a shallow arch with short horizontal flanges to either side. The detail can be seen in the canopy over the front door, atop the two story bay window, and above the second floor grouping of leaded glass windows on the front façade.

Rath House (Inland Architect)

The Harry M. Stevenson house at 4950 N. Sheridan Road dates to 1909 and is a rare survivor of the large homes that lined the street in the first decades of the 20th century. The house, referred to today as the Colvin house for its second owner, features a distinctive Maher dormer, second floor windows recessed behind columns, and a motif of tulips and triangles. It has been restored in recent years and now functions as an events venue.

Stevenson/Colvin House (Eric Allix Rogers)

The Ernest J. Magerstadt house at 4930 S. Greenwood Avenue, built in 1908, is considered one of Maher’s finest designs, although it is not designated a landmark. The narrow lot required a side entrance, providing the opportunity for a broad front porch emphasizing the horizontality of the house. Poppies form the motif in the carved porch columns, leaded glass windows, and mosaics. The house was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1960s, as seen in the photographs below.

Magerstadt House (Library of Congress)

Magerstadt column detail (Library of Congress)

Maher was hired in 1901 by Lucius Fisher to design a trophy gallery in the art gallery of the former Samuel Nickerson house at 40 E. Erie Street. Work in the room included tall cherry bookcases for Fisher’s rare book collection, a large center table, and the huge wood-burning fireplace faced in glass mosaics reflecting the Art Nouveau, executed by Giannini & Hilgart. The most prominent feature of the room is the leaded glass dome featuring four trees in fall colors set against a turquoise sky. The house now operates as the Driehaus Museum, where the room is known as the Maher Gallery.

Maher Gallery (Driehaus Museum)

Evanston once boasted two of Maher’s most significant buildings. James Patten, mayor of the town from 1901 to 1905, commissioned Maher to design a home in 1901 that was unique for its day. Located at 1426 Ridge Avenue, the imposing residence was constructed of enormous stone blocks; architect Stuart Cohen referred to the house as “an abstracted modern day Renaissance palazzo.” The thistle motif was used throughout, including windows, draperies, and wall decoration.

Patten House (Inland Architect)

The house was demolished after being donated to Northwestern University, but the exceptional wrought iron fence still surrounds the three houses built in its place. Significant elements were salvaged and are now housed in various museums.

Patten House window (Halim Time & Glass Museum)

As president of the board of trustees of Northwestern, Patten also provided Maher with the commission to construct the Patten Gymnasium, which he funded in 1908 with a gift of $310,000. The building is a monumental example of Maher’s flanged segmental arch, which conveys the arched steel truss construction. Distinctive light standards were located curbside in front of the building, which contained a gymnasium, a 10-lane running track, and an indoor baseboard diamond. Northwestern demolished the building in 1940.

Patten Gymnasium (Inland Architect)

Maher’s best-known work in the Chicago area is Pleasant Home, designed in 1897 for John Farson, at the intersection of Pleasant Street and Home Avenue in Oak Park, and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1996. Maher considered this an important commission and a “type for an American style” that he was creating. The design is marked with strong symmetry and horizontality set amidst a raised garden behind an ornamental wrought iron fence. The motif rhythm theory incorporates the American honeysuckle, the lion’s head, and the shield, seen in the leaded glass windows, mosaics, woodwork, light fixtures, and furniture. The house is owned and operated by the Park District of Oak Park and is open for tours.

Pleasant Home (Eric Allix Rogers)

Pleasant Home interior (Eric Allix Rogers)

Maher designed a sizable number of buildings outside the Chicagoland area. The largest concentration can be found in Wausau, Wisconsin, where he constructed six homes and renovated two others. The most significant is the home commissioned by Hiram and Irene Stewart, completed in 1906. The flanged segmental arch and tulip motif unify the design of the large home, which still contains its original leaded glass windows, chandeliers, wall sconces, fireplace mosaic, and woodwork. A tapestry on the wall is believed to have been a gift from Maher to the Stewarts. The home is operated as the Stewart Inn Boutique Hotel, the only Maher-designed house in the country available for an overnight stay.

Stewart Inn (Photo by Tom Krueger)

Stewart Inn living room (Photo by Tom Krueger)

Following World War I, Maher was joined in his practice by his son Philip, allowing him more time to focus on community planning, with projects executed for Glencoe, Kenilworth, and Hinsdale. Having been elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1916, he was elected president of the Illinois chapter in 1918. As chair of the Municipal Art and Town Planning Commission of the Illinois chapter, he joined with sculptor Lorado Taft in spearheading the restoration of the Fine Arts building from the World’s Columbian Exposition, which opened as the Museum of Science and Industry through a multi-million dollar gift from Julius Rosenwald.

George Maher in the 1920s

Mental health challenges marked his final years, a recurrence of a nervous condition first experienced in the early 1890s. Extended stays at institutions did little to relieve his symptoms, and he died at his summer home in Douglas, Michigan on September 12, 1926, the result of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was just 61 years old. Philip Maher continued the practice, designing such prominent buildings as the Woman’s Athletic Club at 626 N. Michigan Avenue and the two Art Deco co-op buildings at 1260 and 1301 N. Astor Street.

On Sunday, June 9, 2024, Glessner House will hold its annual gala, “Celebrating Architect George W. Maher” at the Maher-designed Kenilworth Assembly Hall. The event will include brief remarks on the restoration of the hall, and an opportunity to visit the “Centennial Homes” exhibit at the Kenilworth Historical Society across the street. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit:

https://www.glessnerhouse.org/events/2024-gala-maher